Can exercise reverse the ageing process?

- Published

Irene Obera (l), Emma Maria Mazzenga and Constance Marmour compete at the World Masters Athletics Championships in 2015

While many in their 80s and 90s may be starting to take it easy, 85-year-old track star Irene Obera is at the other end of the spectrum.

Setting multiple world athletics records in her age category, she is one of a growing band of "master athletes" who represent the extreme end of what is physically possible later in life.

Another is John Starbrook, who at 87 became the oldest runner to complete the 2018 London Marathon.

Studies suggest regular exercise is more effective than any drug yet invented to prevent conditions facing older people, such as muscle loss, external.

To reap the full benefits, this pattern of behaviour should be laid down in a person's teens and early 20s.

What can we learn from elderly athletes?

Studying master athletes - sportspeople aged 35 and over - gives us an idea of what is physically possible as we age, external.

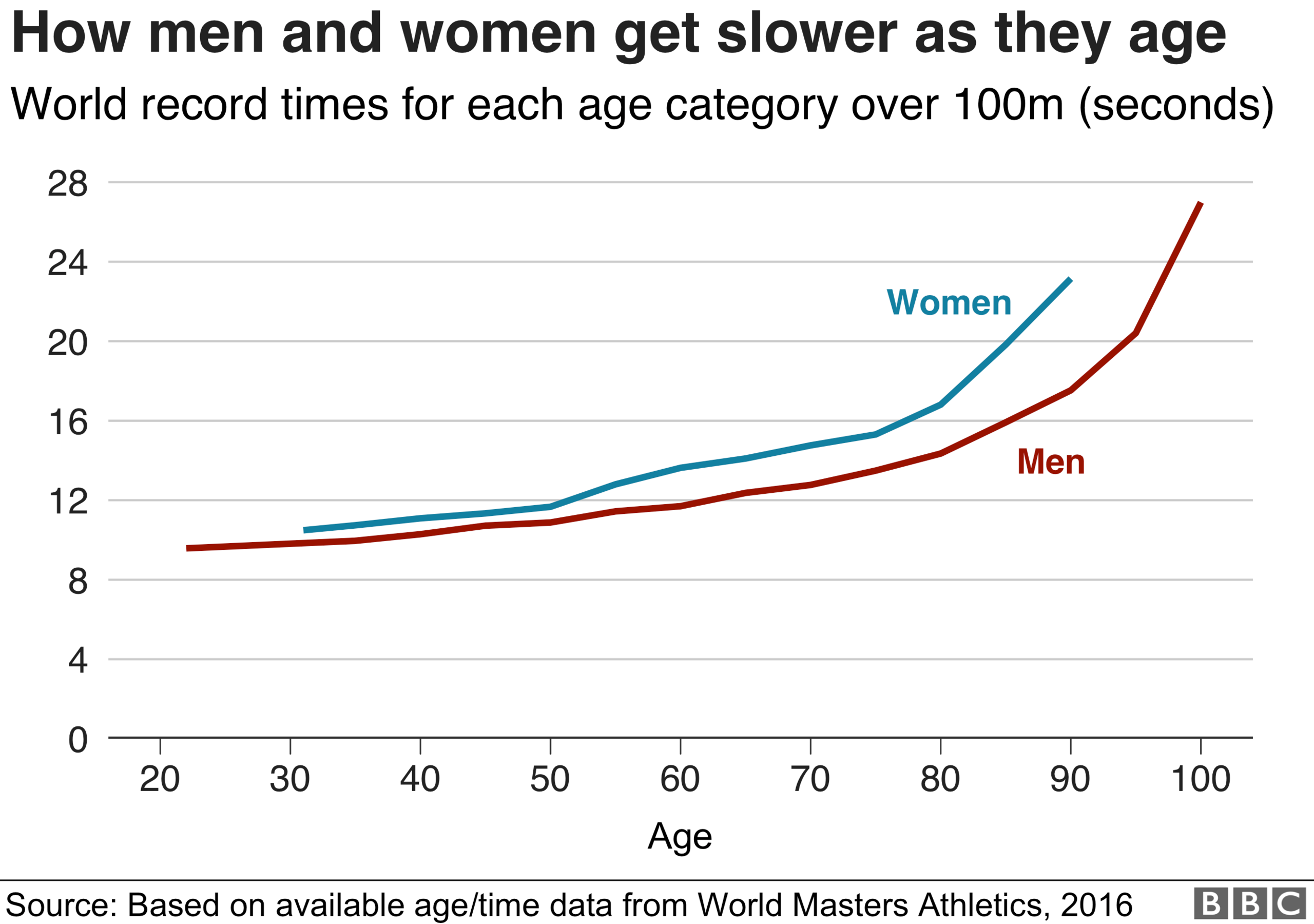

Analysing the world record performance times of each age group unsurprisingly reveals that physical ability does ultimately diminish, the older you get - but doesn't fall off rapidly until after the age of 70.

It is reasonable to assume these top athletes have a healthy lifestyle in general; as well as exercising, they follow a balanced diet and don't smoke or drink heavily.

So their results can help us determine how much of this decline is due to the ageing process itself, external.

Can exercise reverse the ageing process?

The greater health of older exercisers compared to their sedentary counterparts can lead people to believe physical activity can reverse or slow down the ageing process.

But the reality is that these active older people are exactly as they should be.

In our distant past we were hunter-gatherers, and our bodies are designed to be physically active.

So, if an active 80-year-old has a similar physiology to an inactive 50-year-old, it is the younger person who appears older than they should be, not the other way around.

Kazuyoshi Miura, 52, is the world's oldest professional footballer

We often confuse the effects of inactivity with the ageing process itself, and believe certain diseases are purely the result of getting older.

Actually, our modern sedentary lifestyles have simply speeded up our underlying age-related decline. This contributes to the onset of diseases such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and cancer, external.

Many of us are simply not active enough. In England fewer than half of 16-24 year olds, external meet the recommendation for aerobic and muscle strengthening exercises; for 65-74 year-olds, it falls to fewer than one in 10.

Quality of life

Not only does exercise help prevent the onset of many diseases, it can also help to cure or alleviate others, external, improving our quality of life.

Recent studies of recreational cyclists aged 55-79 suggest they have the capacity to do everyday tasks very easily and efficiently because nearly all parts of their body are in remarkably good condition.

The cyclists also scored highly on tests measuring mental agility, mental health and quality of life, external.

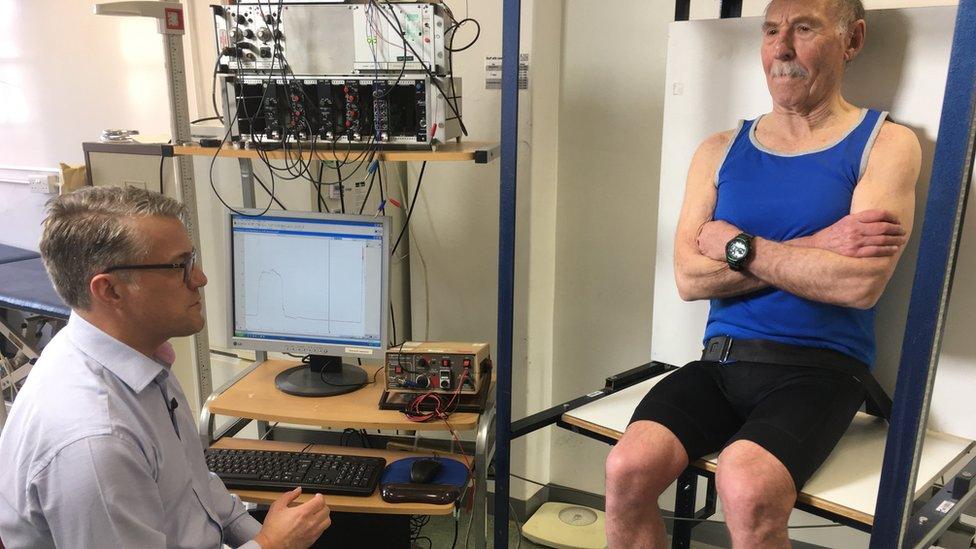

Professor Stephen Harridge (l) and Professor Norman Lazarus, who is aged 82 and has the immune system of a 20-year-old

The younger you start exercising the better.

Analysis of American adults, external aged 50-71 found those who had exercised between two and eight hours a week from their teens through to their 60s, had a 29-36% lower chance of dying from any cause over the 20-year study period.

The study suggests active young people should keep their activity levels up, but also that those aged 40 and above may be able to become more physically active and reap similar benefits.

Master athletes

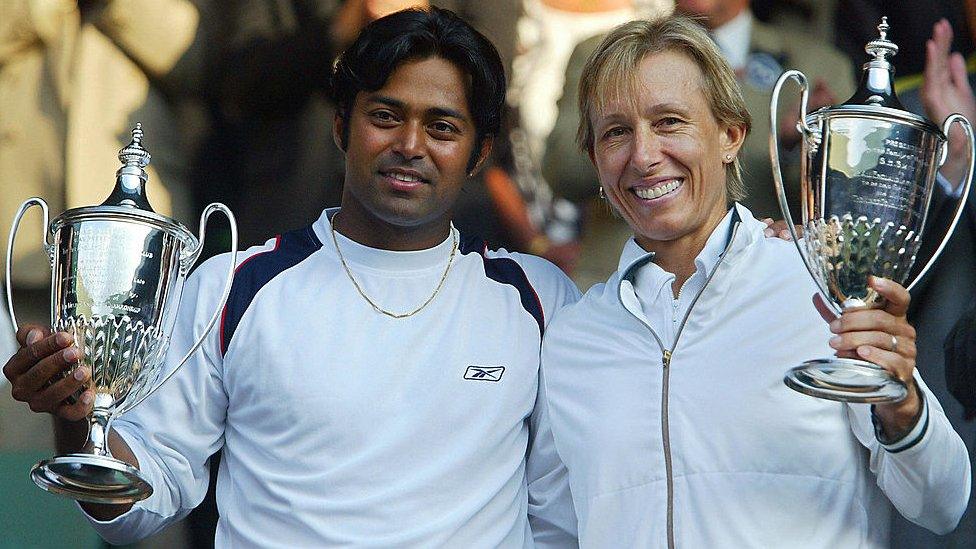

Martina Navratilova became the oldest main draw Wimbledon tennis champion, external at the age of 46

Striker Kazuyoshi Miura, 52, of Yokohama FC is the world's oldest professional footballer.

Otto Thaning became the oldest person to swim the English channel at 73, while 71-year-old Linda Ashmore was the oldest woman to do the same thing., external

Robert Marchand cycled 14 miles in an hour in 2017 at the age of 105, setting a new record

Modern problems

In today's world we have largely been able to get away with problems related to our inactivity, by leaning on the crutch of modern medicine for support.

But while our average life expectancy has increased quite rapidly, our "healthspan" - the period of life we can enjoy free from disease - has not.

Many benefiting from projected life expectancy increases by 2035 will spend their extra years with four diseases or more, external, according to a study in England.

Martina Navratilova won the mixed doubles at Wimbledon in 2003 at the age of 46

While pharmaceuticals are improving all the time, exercise can do things that medicine cannot.

For example, there is currently no drug available that can protect against loss of muscle mass and strength, the biggest factor in our loss of physical function.

Ageing population

Being more active is not only better for an individual, it is also vital for the functioning of our wider society as it ages.

In 2018, almost one in five Britons were over 65, external, while one in 40 were over 85.

The number of people aged 65 and over is projected to rise by more than 40% in the next 16 years.

The average 85-year-old costs the NHS more than five times as much as a 30-year-old, analysis suggests.

What can you do?

Most people should not be aiming to become a world-beating athlete in their advanced years; they don't need to be to reach optimal health.

Instead, incorporating small regular bouts of physical activity - brisk walking or ballroom dancing - into your routine is the key.

Physical activity is one of the cornerstones of a healthy life. Even if you can't be a competitive athlete, starting to regularly exercise in your 20s and 30s is likely to pay off later on.

And if you're past that point, just gently becoming active will do a huge amount of good.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from experts working for an outside organisation.

Stephen Harridge is professor of Human & Applied Physiology at King's College London.

Norman Lazarus is Emeritus professor at King's College London and is a master cyclist in his 80s.

Edited by Eleanor Lawrie