What are the biggest threats to humanity?

- Published

Human extinction may be the stuff of nightmares but there are many ways in which it could happen.

Popular culture tends to focus on only the most spectacular possibilities, external: think of the hurtling asteroid of the film Armageddon or the alien invasion of Independence Day.

While a dramatic end to humanity is possible, focusing on such scenarios may mean ignoring the most serious threats we face in today's world.

And it could be that we are able to do something about these.

Volcanic threats

In 1815 an eruption of Mount Tambora, in Indonesia, killed more than 70,000 people, while hurling volcanic ash into the upper atmosphere.

It reduced the amount of sunlight hitting the surface of the Earth, triggering what has become known as the "year without a summer".

The 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora killed more than 70,000 people

Lake Toba, at the other end of Sumatra, tells a still more sinister story. It was formed by a truly massive super-volcanic eruption 75,000 years ago, the impact of which was felt around the world.

It has been suggested that the event led to dramatic population decline in early humans, although this has recently been questioned.

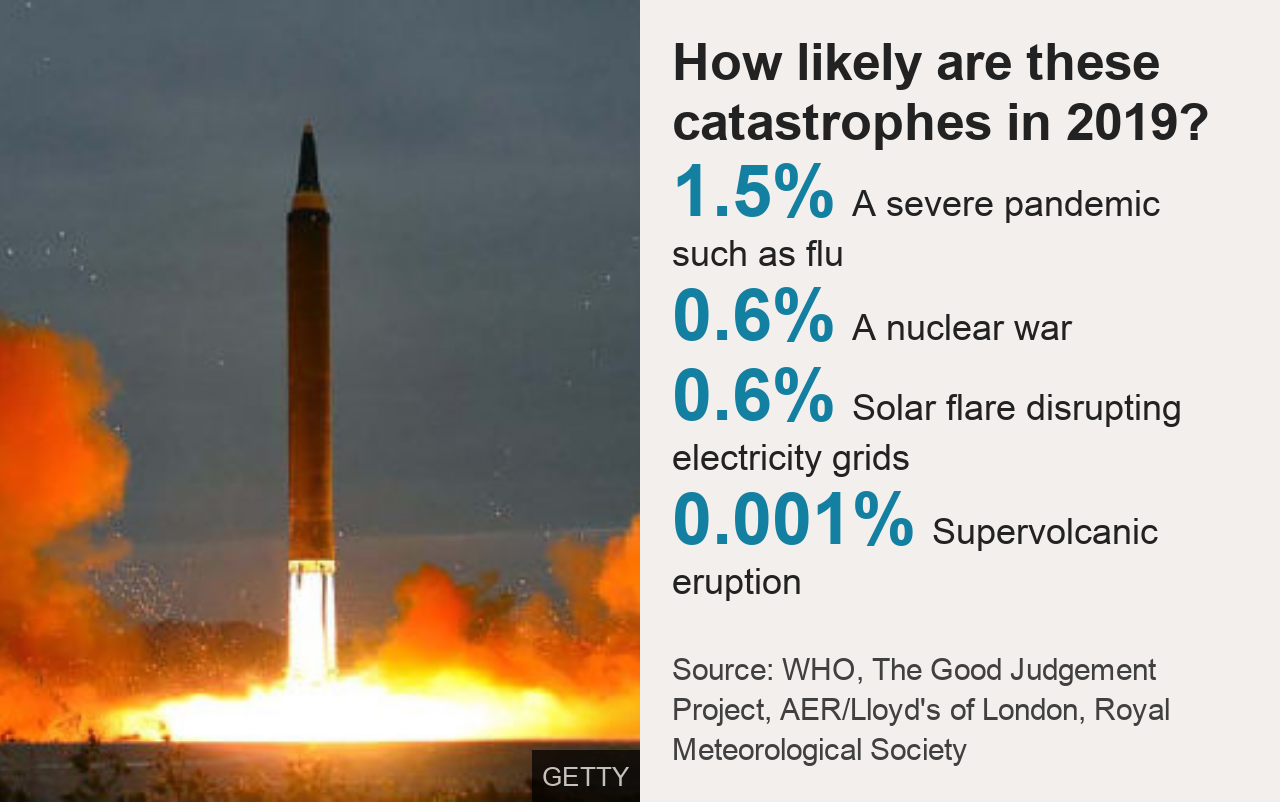

But while the prospect of a super-volcanic eruption is terrifying, we should not worry too much. Super-volcanoes and other natural disasters, such as an asteroid striking Earth or a star exploding in our cosmic neighbourhood, are no more likely in 2019 than any other year. And that is not very likely.

Growing threats

The same cannot be said for many global threats induced by people.

For example, the World Health Organization, external and the World Economic Forum, external both listed climate change and its effects as one of their top risks for 2019.

Recent UN talks heard climate change was already "a matter of life and death" for many regions. While many, including Sir David Attenborough, believe it could lead to the collapse of civilisations and the extinction of "much of the natural world".

The threats are complex and diverse, from killer heatwaves and rising sea levels to widespread famines and migration on a truly immense scale.

Also increasing are the potential risks from novel technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI).

The scenarios range from increasingly sophisticated cyber-weapons that could hold an entire nation's data to ransom, external, to autonomous algorithms that could unwittingly cause a stock-market crash.

Another threat is the possibility of a nuclear war.

While many focus on rising tensions between global powers, new technologies may also be making us less safe.

This is because of both the "entanglement" of nuclear and conventional weapons and the risk that AI could help unleash nuclear war, external.

Avian flu exercise in Hebi, China

Another risk that may be increasing is that of global pandemics. Influenza, for example, is thought to kill an average of 700,000 people, external and cost the global economy $500bn (£391bn) per year.

Increasingly dense and mobile human populations have the potential to see new influenza strains spread easily. And this raises concerns about a future outbreak like the 1918 Spanish Flu, which killed up to 50 million people.

However, widespread vaccination programmes and other disease prevention measures help reduce this risk.

How to calculate the chance of an existential risk

Look at historical or geological records. We can keep track of some events such as super-volcanoes and asteroid impacts

Find a natural precedent. When scientists explored the risk the Cern reactor might pose, they looked at similar environments that occur in stars

Build a model. Scientists use sophisticated atmospheric models to explore the future of our climate

For threats that can't be modelled, scientists generate insights by engaging in war-gaming and other exercises

The UK government also maintains a register of national risks, external, including floods, space weather and disease

A disruptive future

While these threats are real, the greatest danger we face in 2019, when viewed from a global perspective, probably lies elsewhere.

With almost eight billion people living on Earth, we are increasingly reliant upon global systems to sustain us. These range from the environment that provides us with food, water, clean air and energy, to the global economy that turns these into goods and services.

Yet, from declining levels of biodiversity to overextended infrastructure and supply chains, external, many of these systems are already stressed to breaking point. And rapid climate change is only making things worse.

Given this, it may be that global risks should not be defined by the size of the disaster that caused them, but by their potential to disrupt these vital systems.

A volcanic ash cloud prompted disruptions to flights around the world in 2010

The potential is hinted at in recent examples of cascading effects.

The 2010 eruption of Iceland's Eyjafjallajökull volcano, external killed no-one but closed air traffic over Europe for six days. And, in 2017, the relatively unsophisticated WannaCry ransomware attack shut down parts of the NHS and other organisations around the world.

Since almost everything we rely on also depends on a functioning electrical, computing and internet system, anything that would damage this - from a solar flare to a high atmosphere nuclear explosion - could cause very widespread harm.

Disaster prevention

There may, however, be new ways to reduce this risk.

There is an old story of King Canute of the Danes commanding the sea to retreat. He knew he would be unable to hold back the tide and a similar sense of powerlessness can easily overtake us when we consider potential future catastrophes.

However, the truth is that the Danes have been pushing back their shoreline for generations: building dykes and draining marshes to protect themselves from the oncoming tide.

Sometimes it is better to protect ourselves by thinking of ways to make humanity more resilient to disasters that are to come.

And this could give us the best way of ensuring that 2019 - and beyond - are safe years for humanity.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from experts working for an outside organisation.

Dr Simon Beard, external and Dr Lauren Holt, external are research associates at the Centre for the Study of Existential Risk, external.

The CSER, based at the University of Cambridge, studies the mitigation of risks that could lead to human extinction or the collapse of civilisation.

Edited by Duncan Walker