How to reduce rural ambulance waits

- Published

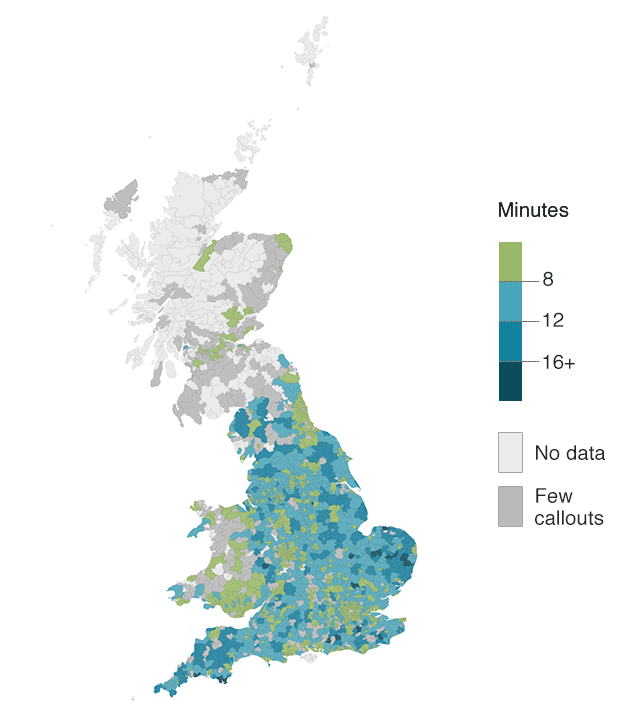

The NHS is promising to reduce the gap between how long it takes to get a 999 response to critically injured patients in rural and urban areas.

A BBC News investigation into the highest-category callouts has found rural areas waited over 50% longer.

That equates to four minutes - something that can make the difference between life and death for those in cardiac arrest, stab victims and patients struggling to breathe. So what can and is being done?

Source: Ambulance trusts. Data is shown for postcode districts with more than nine highest category callouts in January-October 2018. Districts with 10-49 callouts are labelled "low numbers". Northern Ireland does not use comparable categorisation.

Is more money the solution?

Every part of the health service would readily accept more money.

About £2bn a year is spent on answering more than 10 million urgent calls - although only about 5% of these are classed as "immediately life-threatening".

That sum equates to just over 1.5% of the health budget.

More money could certainly help deploy extra paramedics and vehicles, to ensure better coverage in rural areas.

But even those working in the service acknowledge there is a limit - crews sitting around for long periods with nothing to do is clearly not the best use of NHS resources.

Volunteer lifesavers

One of the most important steps in rural areas is training up members of the community to help answer these high-priority calls.

These are known as "community first responders" and volunteer to be on call to help critically injured patients if paramedics are not going to be on the scene quickly.

Some police and fire crews have also been trained to lend a hand.

While thousands of these volunteers have been trained, the ambulance service says it can always do with more.

Community first responder Paul Elliott says the system is facing significant pressures

Paul Elliott, a St John Ambulance community responder who covers the Bodmin area in Cornwall, even carries a defibrillator in his car, to treat cardiac-arrest patients.

"We're supposed to travel within a three-mile radius of our home locations but because we're in such a rural area, with some tricky geography, we can go up to 20 miles to help people sometimes," he said.

The service was under "significant pressure" and needed more full-time staff and first responders like him, Mr Elliott said.

But the problem is that in some areas it can be a challenge keeping these volunteers because of the demands placed on them.

BBC News has heard from one former community responder who served Wells-next-the-Sea, in north Norfolk, the place with longest response times, who said he had given up after being left for too long tending to badly injured patients.

Getting bystanders to help

Call-centre staff can instruct members of the public to use defibrillators

No matter where a patient is when a life-threatening situation develops, the simple fact remains in all probability a member of the public will be on the scene more quickly than a trained response.

And they can play a critical role. Take cardiac arrests, for example. A bystander can provide cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) to patients. Even those who have not been trained can be talked through the process by control-room staff and told where to access community defibrillators to deliver electric shocks to restart the heart.

Action like this can double the chances of survival before 999 help arrives. Every minute without treatment reduces the chances of surviving a cardiac arrest by 10%.

The problem is that the UK has one of the lowest rates of bystander involvement - less than half of out-of-hospital cardiac arrests see members of the public get involved.

It is one of the reasons why the announcement last year to introduce first-aid training into schools has been so widely welcomed and work continues to ensure there are enough defibrillators situated in community locations.

Adjusting the targets

The way ambulance crews answer calls in England, Scotland and Wales has changed in recent years.

All have introduced a system that prioritises a smaller number of calls for the quickest response.

Today, just one in 20 calls is treated as the highest-priority, whereas traditionally about a third of calls were.

Out went things such as strokes, as the research suggested what mattered most to those was whether they ended up at the right hospital not how quickly help arrived at the scene.

This is allowing crews to make faster responses to the most-in need patients, according to Adam Brimelow, of NHS Providers.

But does this help rural areas? The BBC News investigation looked at response times from January to October last year - after these changes were brought in.

It was not possible to look at a historical trend over time.

Academic research carried out during the piloting phased of the new system in England suggested it might reduce variation.

But the NHS in England believes it will. A spokesman for the service said there was now a "strong incentive to tackle the longer waits historically seen for those who live in rural and remote areas".

Indeed, even in Northern Ireland, which uses the old system, there is now a desire to follow the lead of England, Wales and Scotland.

There may be some way to go, but many think the ambulance service is on the right track.

- Published8 February 2017

- Published8 February 2017

- Published6 January 2017

- Published12 December 2016

- Published13 September 2016