Measles: How a preventable disease returned from the past

- Published

Measles is one of the world's most infectious illnesses but until recently cases had been declining. So what's led to recent outbreaks?

Rockland County, in New York state, declared a state of emergency following a severe re-emergence of the preventable virus.

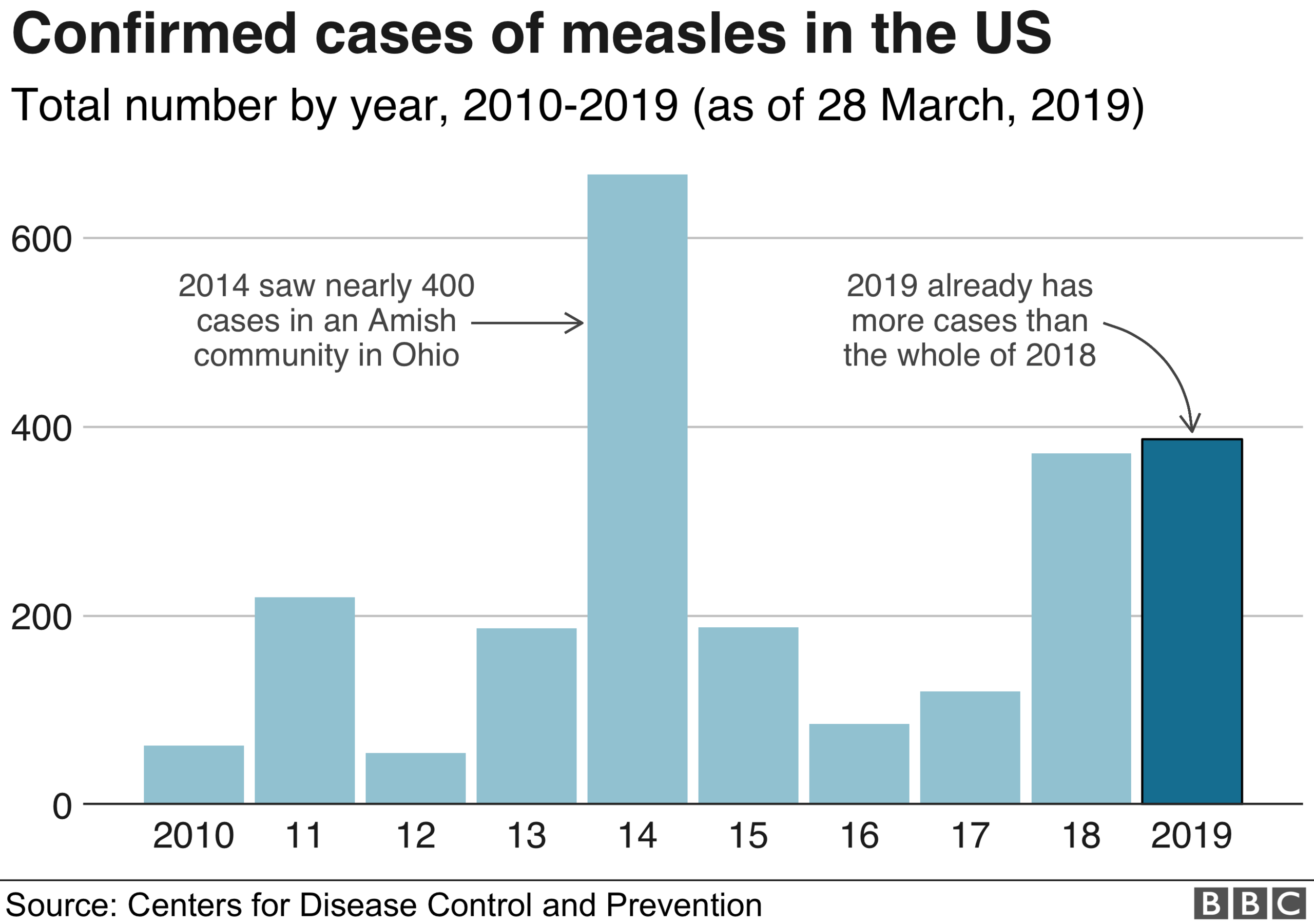

It's far from an isolated case, with the US already on course this year to see the most measles cases since 2000, when the disease was officially eliminated.

Other countries, such as Mexico, France and Madagascar, external, have seen similar outbreaks in communities with gaps in immunity.

In most cases, measles is relatively minor but it can also lead to potentially life-threatening complications, external such as pneumonia, meningitis and brain inflammation.

Although still far below historical levels, the disease has been on the rise for several years. Reported cases rose by 31% in 2017 on the year before, leading to about 110,000 deaths worldwide.

According to Unicef, 98 countries reported an increase in measles cases in 2018, with almost three-quarters of these occurring in 10 countries.

What's happening to vaccinations?

Successful vaccination programmes have ensured measles has become rare in many places.

When a measles vaccine became widely used in the 1980s, cases fell significantly, eventually leading some countries to declare it had been eliminated.

Before then, large epidemics of measles occurred every few years.

For example, in 1967, the year before measles vaccine was introduced in England and Wales, there were almost half a million reported cases and 99 deaths. By 1998, this had fallen to an all-time low of 56 cases and no deaths.

So what accounts for the alarming recent increases?

A vaccination target of 95% creates "herd immunity" in a community, to prevent this highly infectious disease from spreading.

All the measles outbreaks have taken hold in areas where there is not enough immunity but the reasons behind this differ from place to place.

The high-profile anti-vaccination movement has become influential in parts of the US and Europe.

Despite overwhelming scientific evidence supporting vaccination, "anti-vaxxers" can believe vaccines are unnecessary or harmful.

They sometimes embrace conspiracy theories around "big pharma" and are distrustful of government.

In the UK, a scare over the safety of the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine, following now discredited research, had a major impact for a time.

In 2004, first-dose MMR coverage fell to 80% in England and 78% in Wales

Two decades on, uptake has recovered, with over 90% of UK two-year-olds receiving the vaccine in 2017-18.

But many adolescents and young adults not given the MMR as infants are now catching measles.

We may also see future outbreaks of rubella - German measles - in this age group, a particular concern as they reach childbearing age.

Usually a mild disease, rubella can be catastrophic if caught in the early stages of pregnancy, causing serious vision, hearing, heart and learning problems in the unborn baby.

Beyond 'anti-vaxxers'

In other countries, reasons behind falling vaccination rates are very different.

In Ukraine, for example, public trust in vaccination was severely shaken in 2008, following the death of a teenager after a measles vaccination, which, although unconnected, led the government to halt the vaccination campaign.

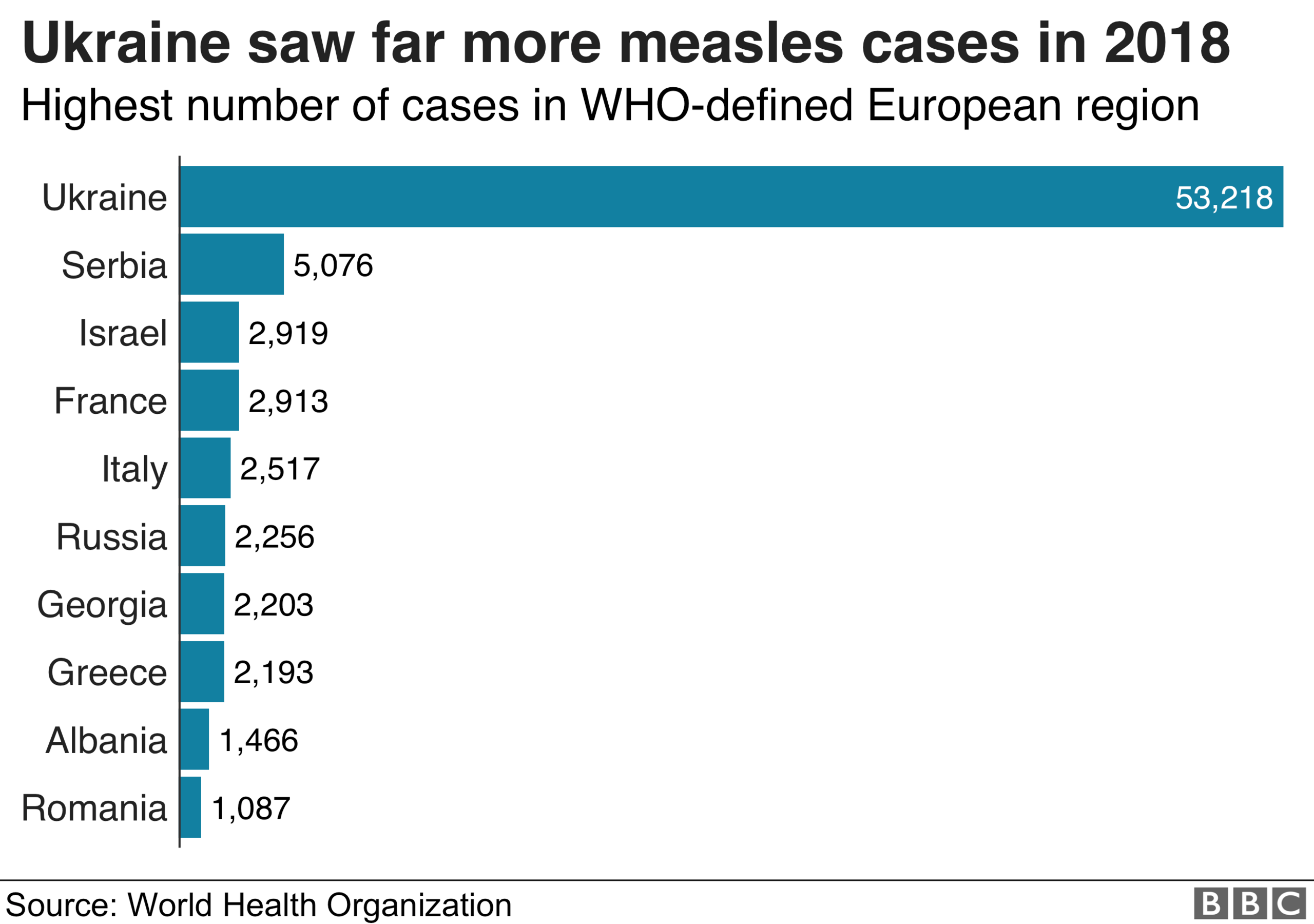

By 2016, in a situation made worse by political unrest, health service corruption and vaccine shortages, Ukraine had one of the lowest uptakes of measles vaccine in the world, with only one in three of six-year-old children protected with two doses of vaccine.

Although over 90% of six-year-olds are now protected, the reservoir of young people left unprotected has allowed measles to take hold.

The country has become a hotspot for measles, with 54,000 cases in 2018, compared with about 5,000 in the previous year.

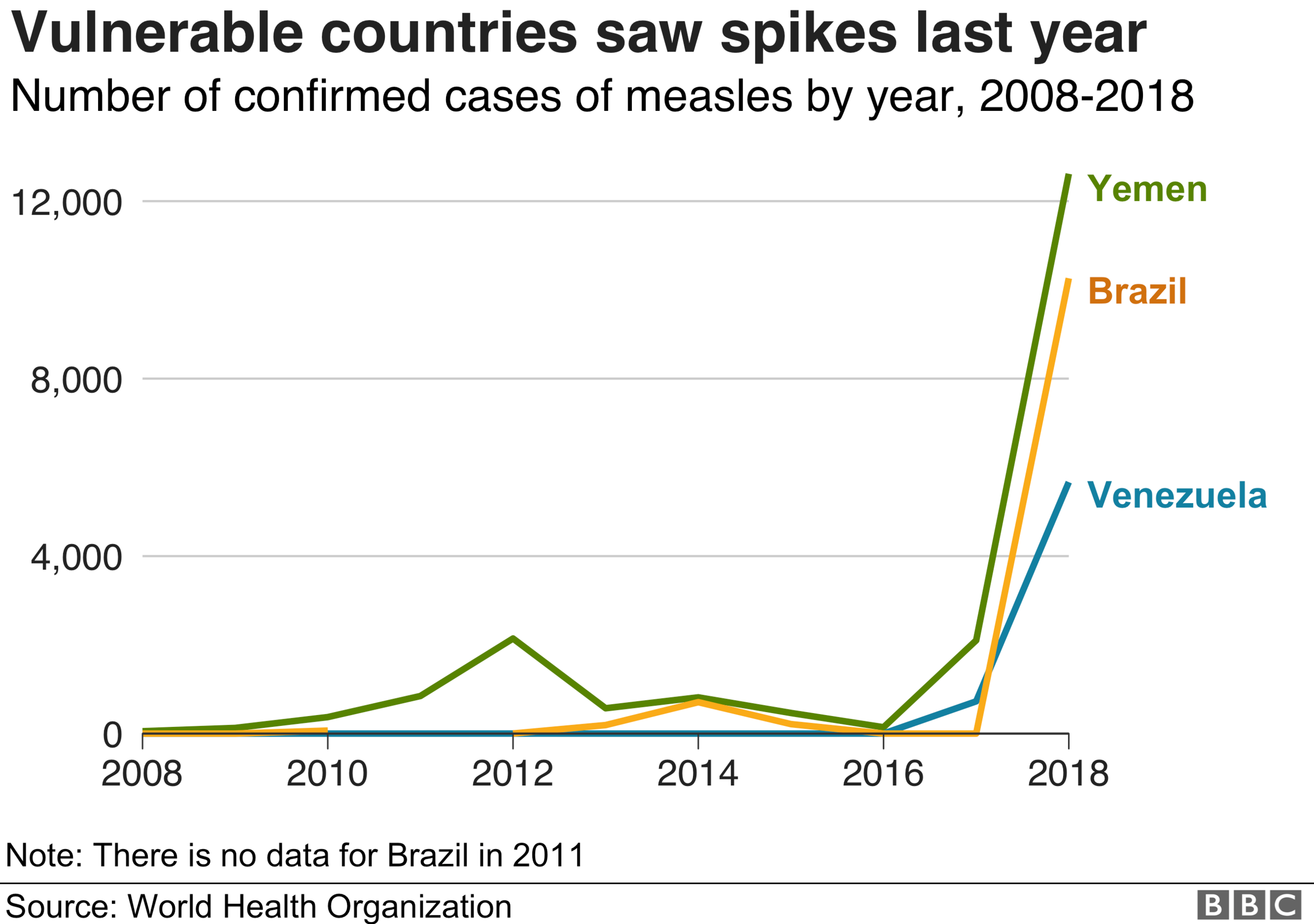

Immunity levels have also fallen in countries where the health system has collapsed, such as Yemen, which is in the midst of civil war, and Venezuela, which tackling a serious economic crisis.

This can have knock-on effects on other countries too, such as in Brazil, which has experienced mass migration from Venezuela.

What is measles?

Measles is a highly infectious virus spread in droplets from coughs, sneezes or direct contact

It can hang in the air or remain on surfaces for hours

Measles often starts with fever, feeling unwell, sore eyes and a cough followed by a rising fever and rash

At its mildest, measles makes children feel very miserable, with recovery in seven-10 days - but complications, including ear infections, seizures, diarrhoea, pneumonia and brain inflammation, are common

The disease is more severe in the very young, in adults and in people with immunity problems

Measles is still a major cause of child death in many low-income countries, although the measles vaccine is thought to have prevented more than 20 million deaths in 2000-17

How are countries responding to these outbreaks?

Some countries are moving toward mandatory vaccination and many more have tightened up existing requirements.

Italy and France have extended existing requirements with fines and restricted school attendance. And Germany is currently discussing making measles vaccine mandatory.

In New York's Rockland County, unvaccinated children have been banned from public places for 30 days. But it is difficult to see how this could be effectively enforced and there is little evidence that mandatory vaccination is always the best approach.

Those determined to not vaccinate will find a way round the system, for example by home-schooling or paying a fine.

Meanwhile, parents on the fence about vaccination may become more resistant if they feel they are not being given a choice. A better solution may be the opportunity to have a conversation with a health professional to respond to their concerns.

Meanwhile, checking vaccination status on entry to nursery and then to school would act as a useful reminder to parents and reinforce their importance.

As most under-immunisation results from difficulties accessing services, tailored immunisation services would also be helpful.

For example, an innovative response to a measles outbreak in the London borough of Hackney was the "spotty bus" - a mobile immunisation unit that toured the neighbourhood, parking in school playgrounds and supermarket car parks, vaccinating almost 1,000 children whose parents simply needed easier access to immunisation services.

It is not enough for health services to expect parents to come to them.

Taking a proactive approach and offering these kinds of easily accessible vaccine programmes would help to prevent further outbreaks.

Since the global fall in vaccination rates mainly stems from practical or logistical issues, it is often more important to have an everything in place for a successful vaccination programme.

This means having enough vaccines to go around, via services that are well organised, easy to access and supported by government efforts to increase public trust in vaccination.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from an expert working for an outside organisation.

Helen Bedford, external is a professor of children's health at University College London.

You can follow her on Twitter here, external.

Edited by Eleanor Lawrie