Inside the UK's drug buyers' clubs

- Published

Luis Walker is hoping his mother will be able to buy a drug from Argentina, to help treat his cystic fibrosis

In a meeting room tucked away behind a clothes market in east London, around 10 people are meeting to discuss how they might import drugs from South America.

This group of patients and parents are hoping to buy a copy or generic version of Orkambi - a drug which helps slow the decline in lung function and decrease the risk of infections in people with cystic fibrosis.

More than 10,000 people in the UK have the debilitating genetic condition, which affects the lungs and other organs.

Much like the HIV treatment buyers' club of the 1980s - made famous by the Oscar-winning film, Dallas Buyers Club, groups like these are offering an alternative to those who have been losing out on the drugs used to treat their condition.

Licensed for use in the UK since 2015, Orkambi is not available from NHS England, except for certain people on compassionate grounds.

In May 2018, more than 1,000 letters were delivered to the prime minister asking Theresa May to intervene personally in the stalemate between NHS England and Vertex, the company that holds the licence to market Orkambi in the UK.

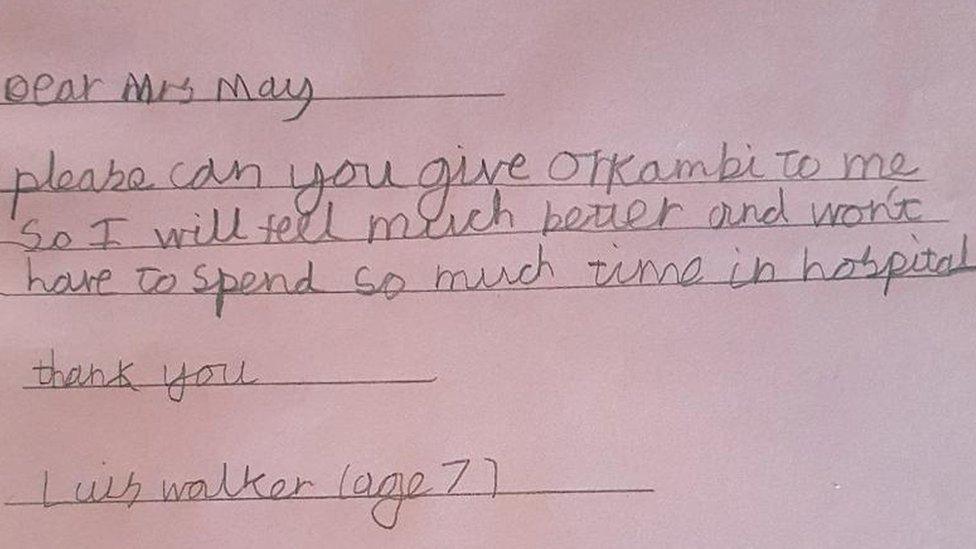

One of those letters was from Luis, then aged seven.

"Please Mrs May, can you give Orkambi to me so I feel much better and I won't have to spend so much time in hospital," he wrote.

After Luis sent his letter to Mrs May, his friends, family, teachers and fellow patients decided to do the same

But more than a year on, little progress has been made in negotiations between NHS England and Vertex.

Vertex put a price tag on the drug of £104,000 per person for a year's supply. But the company told the BBC that it offered the NHS a confidential discount although it won't confirm the figures.

The NHS concluded the amount Vertex was asking for wasn't cost-effective, and instead offered Vertex £500m over five years for several of their drugs.

This, Parliament was told, was the "largest ever financial commitment" in the 70-year history of the NHS. But Vertex rejected the offer.

The Health Select Committee said it appeared to be an abuse of a monopoly position.

NHS England says it has since further improved its offer to Vertex.

Dr Andrew Hill, from Liverpool University, has been looking at issues around access to drugs for many years.

Vertex's monopoly means they're the only company that can sell Orkambi to the NHS. But for 3,000 UK patients with a certain mutation of cystic fibrosis, it is the only drug that works on the underlying causes of the disease.

"[The] people with that disease are stuck," he says.

'No more waiting'

But there is potentially another option for people like Luis and his mother Christina Walker. A so-called generic version of Orkambi - or a copy - is being produced in Argentina. Vertex didn't patent Orkambi there.

So now a collection of patients and parents are taking matters into their own hands. They've formed a buyers' club and are hoping to strike a deal for the generic drug.

Christina attended the buyers' club meeting in east London.

"There can be no more time waiting for those sides to reach an agreement. So in my mind we need to decouple Vertex from this situation," she tells the group.

"My son has lost 20% of his lung function in one year. He needs treatment soon."

Christina Walker (second-left) went to meet a buyers' club in London to try and get the drugs her son needs

The company that makes the drug in Argentina - Gador - is currently asking for £23,000 per patient per year, which they'll drop to £18,000 if this buyers' club can get at least 500 people involved.

The Cystic Fibrosis Buyers' Club hopes to recruit others from around the world - the more people who sign up the better the deal they hope to get, Christina says.

A three-month supply of drugs can be imported legally for personal use and patients are joining together to exercise that right.

Orkambi and Lucaftor, the drug made by Gador, both have the same active ingredients: lumacaftor and ivacaftor.

Like other buyers' clubs Newsnight has spoken to, this group has taken crucial steps to make sure the drugs they're importing contain what they say they do.

The group has worked with a major London NHS hospital to compare independently the amount of active pharmaceutical ingredients in samples of both drugs.

"I think we're pretty confident in the quality of the drugs," says Diarmaid McDonald from campaign group Just Treatment.

But £18,000 is still a lot to pay privately. So could the generic drug become available on the NHS?

"Normally if a drug is patented then only the company that did the original research can sell that drug in that country," Dr Hill says.

One potential solution is a Crown Use, or compulsory licence, which would allow the state to essentially override a patent in the national interest and use cheaper copies of a drug.

Vertex told Newsnight they believe the government will not go for this option because it would undermine the company's efforts to find a cure. It said that companies who claim to be able to produce a product similar to Orkambi have not had to bear the cost of drug discovery and development.

"Though it should be noted that at £30,000 this price is still many times higher than the amount NHS England offered to pay for Orkambi in 2018," a Vertex spokesperson said.

Earlier this year, Vertex also reassured worried investors that a compulsory licence would conflict with the UK government's life sciences strategy, which has the aim of supporting industry and innovation.

But compulsory licenses are being used around the world because governments think the prices companies are charging are too much, Dr Hill says.

"It's legal under World Trade Organization rules," he says.

"It's a question of whether the government has the political will to do it."

People with cystic fibrosis aren't the first to start a buyers' club - there is a growing number in the UK.

A three-month supply of Orkambi can be imported legally for personal use

Will Nutland, a public health doctor, is part of an organisation called PrePster which helps people source cheap, high quality generics of PreP - or pre-exposure prophylaxis - a pill to help reduce the risk of becoming infected with HIV. They started to import from overseas suppliers when the NHS deemed the patented version too expensive.

"Primarily through the use of generic PreP, we've seen about a 60%-75% drop in (new) HIV infections in London, which is unprecedented," Dr Nutland tells the club in east London.

Dr Hill has worked with other buyers' clubs too.

"[There are people] who have hepatitis C, people with pulmonary fibrosis, people with certain cancers, who are importing the drugs [they need] from foreign countries - good quality copies of the drug for their personal use, and they often do this with supervision of NHS doctors," he says.

There is a potential way that the NHS can pay for the generic Orkambi that patients in the cystic fibrosis buyers' club are hoping will happen.

Legally, the NHS can fund a clinical trial of a drug in the name of research, ignoring patents.

The trial can run for as long as it needs, with large numbers of participants.

Around two years ago, the NHS set up a large clinical trial involving using generic PreP. It aims to recruit 26,000 patients who will be monitored by and get their drug on the NHS.

Christina hopes that the buyers' club can have a similar impact on cystic fibrosis that the PrePsters have had on HIV.

"This is the ultimate model. That's very much what we're asking for," Christina says.

"The NHS can collect the information it needs to make a proper assessment about these drugs while getting them speedily to patients."

The Department of Health and Social Care declined to comment.

You can watch Newsnight on BBC Two weekdays at 22:30 or on iPlayer, subscribe to the programme on YouTube, external and follow it on Twitter, external.

- Published11 May 2019