Where not to live if you want a good care home

- Published

High concentrations of substandard care homes in some areas leave families with no choice but to accept an under-performing home for older and disabled relatives, an analysis suggests.

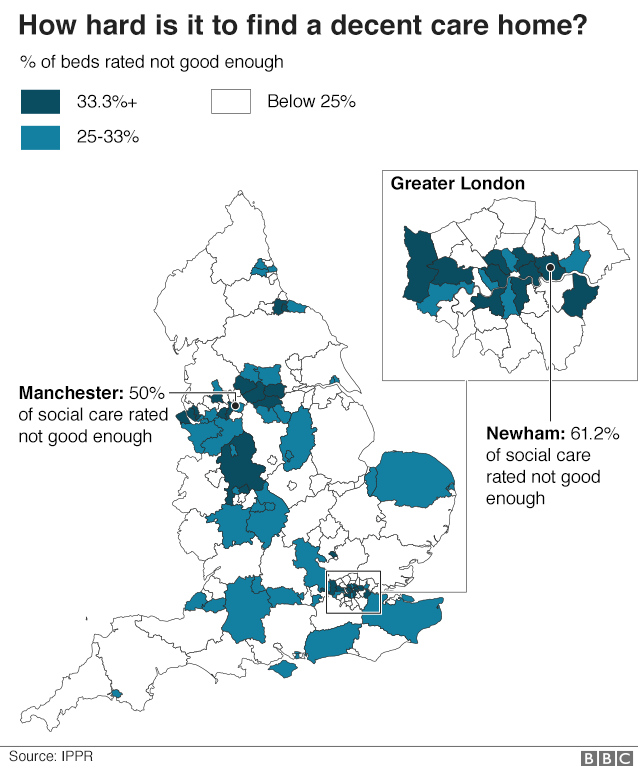

Over a third of beds were in settings rated as not good enough in a sixth of areas, the think tank IPPR found.

In two places - Newham in London and Manchester - at least half were.

Campaigners said high concentrations of substandard care would mean that good homes would be over-subscribed.

In each local authority area the IPPR, which worked with research group Future Care Capital, mapped the proportion of care home places rated as inadequate or requiring improvement by the Care Quality Commission.

Overall, 23% of the 456,000 beds were in settings that fell into one of the two categories.

The best and the worst

But in some places the concentrations were so high that half or more of beds were in under-performing homes.

The London borough of Newham had the highest concentration - more than 60% of beds were in homes judged not good enough. This was followed by Manchester on 50%.

Overall, 26 local authorities had more than a third of beds in sub-standard settings.

By comparison, Southampton, Windsor and Maidenhead, Peterborough and Kingston, in London, all had less than 5% of beds in homes judged not good enough.

Caroline Abrahams, of Age UK, said the situation was "unacceptable" and left some people with "no choice" but to accept sub-standard care homes because good homes would be over-subscribed.

"The sad truth is that following years of underfunding and neglect, the social care system has now more or less completely broken down in some parts of the country," she said.

The IPPR agreed it was a sign of a failing market.

The think tank said costs had been cut in the care sector, and urged the government to take action by investing and reforming social care.

It wants to see tax rises to provide free personal care for all and to help expand the number of beds by up to 75,000, arguing the state could be more involved in running services.

Care companies have complained over recent years they have been squeezed by the low fees paid by councils, which fund most care home places.

The system is means-tested for over-65s, which means there are large numbers of self-funders.

The government said its plans to reform the system would be published in "due course" and pointed out it had announced an extra £1.5bn for the sector for 2020-21 in the recent spending round.

"We expect everyone to be able to access high quality, safe and compassionate care," a Department of Health and Social Care spokesman added.

- Published29 May 2019

- Published4 March 2019