Why 2020 will be a crucial year for the NHS

- Published

The new government is prioritising the NHS - that was made abundantly clear in the Queen's Speech unveiled the week before Christmas.

Promises have been made on everything from money to staffing.

So 2020 looks set to be a crucial year as ministers seek to meet the challenges facing the health service in England head-on.

But what are the most pressing issues for the Westminster Parliament to address in the year ahead?

Reducing waiting times

Health is devolved, meaning the Department of Health and Social Care does not control health policy in the rest of the UK, although Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland will be watching closely to see what it does.

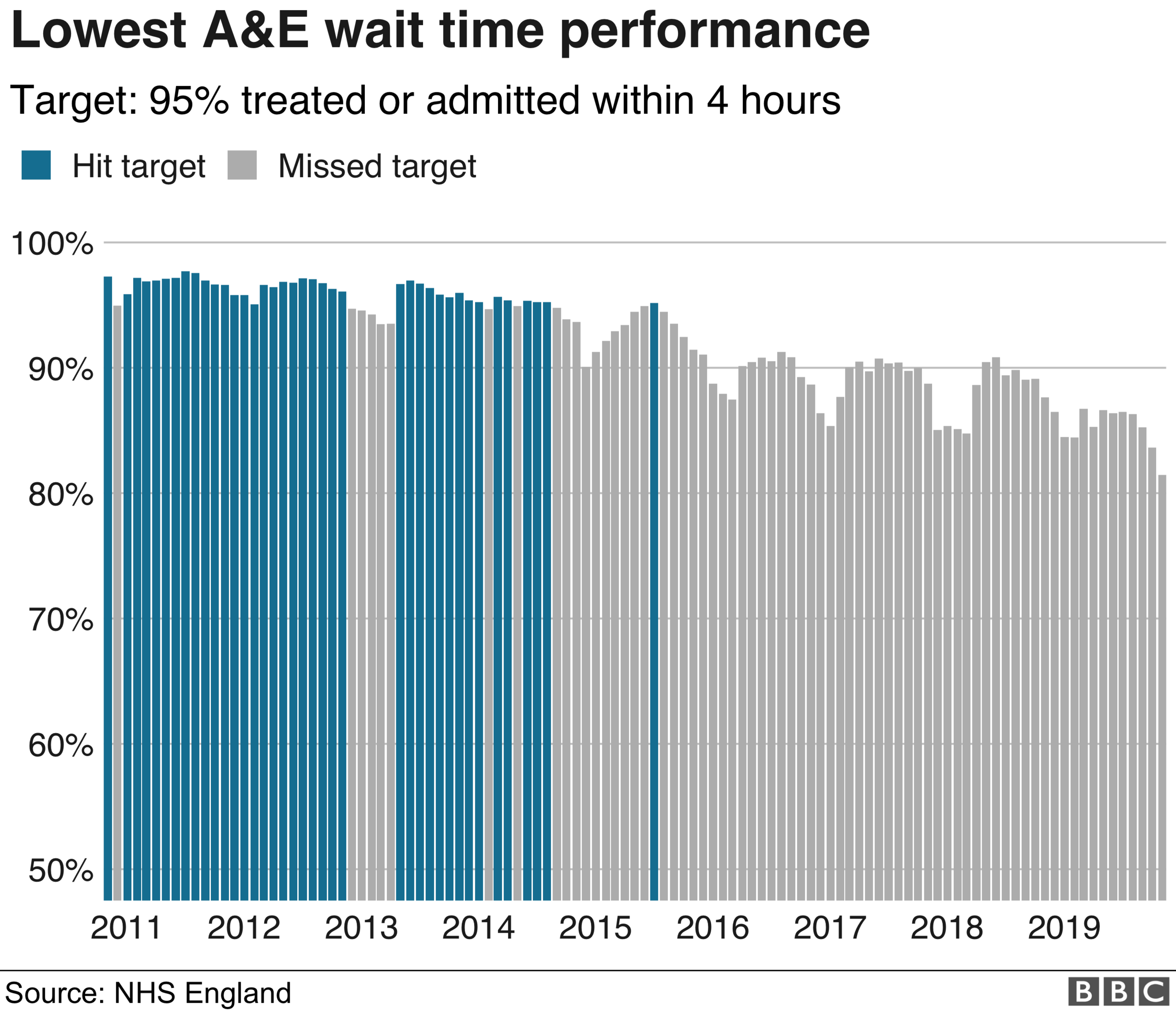

Undoubtedly the most high-profile problem - and the one used by critics to beat the Tories - has been the deterioration in waiting times.

It is now more than three years since any of the three key targets covering A&E, hospital operations and cancer have been met.

Both A&E and routine operations are at their worst levels since the respective targets have been introduced.

The first tranche of the extra funding the NHS is receiving - 3.4% above-inflation rises until 2023 - kicked in at the start of April 2019.

But that still has not been enough to reverse the deterioration. Many predict it will take years before the NHS gets back to where it was a decade ago, when it was regularly meeting waiting time targets.

In the short term, hospitals have to get through winter.

The fact that rates of flu are at a higher level than they were at this point last year is causing concern.

It will not take much added pressure and footfall to throw the NHS into a full-blown crisis.

Tackling care 'crisis' after 20 years of talk

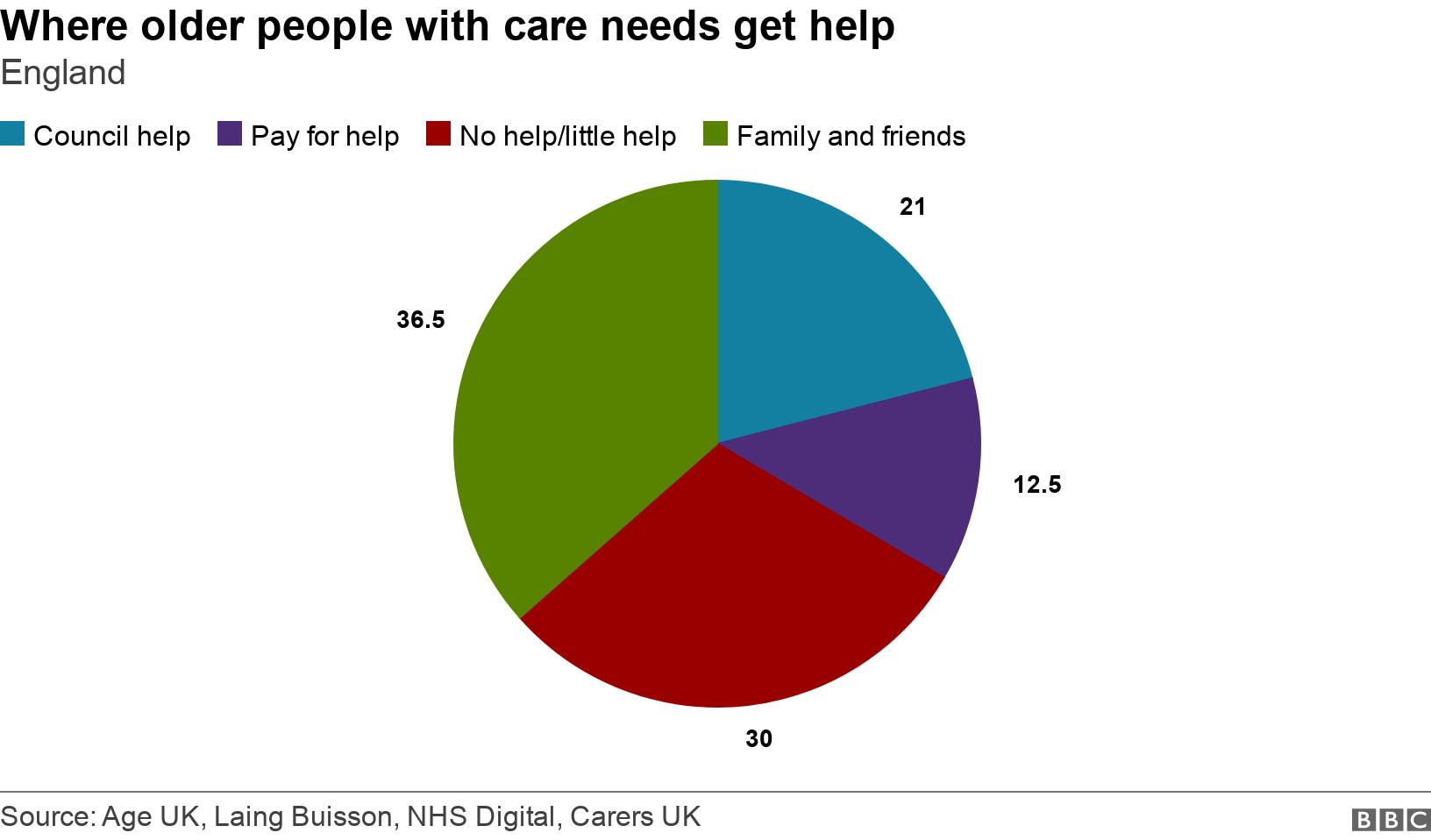

One of the contributory factors in the pressures being felt by hospitals is the lack of care in the community.

One in 20 hospital beds is taken by a patient who is ready to be discharged, but cannot be because support is not available to care for them at home.

The problems are well documented - and the government has already pledged to take action.

In fact, Boris Johnson promised to "fix the social care crisis once and for all" in his first speech on the steps of Downing Street when he took office in the summer.

The election manifesto provided no detail on how the Conservatives would do this, beyond promising that people would not have to sell their own homes to pay for care - only the poorest get help from the state.

Ministers want to set up a cross-party commission, but with both Labour and Liberal Democrats plunged into leadership races after the election, there will be huge pressure on the government to start coming up with plans.

After all, a working group of experts has already spent 18 months drawing up options for the government to consider.

It was set up after the 2017 election - exactly 20 years after Tony Blair came to power promising reform.

After more than two decades of talking, surely the time has come for action.

Filling the gaps

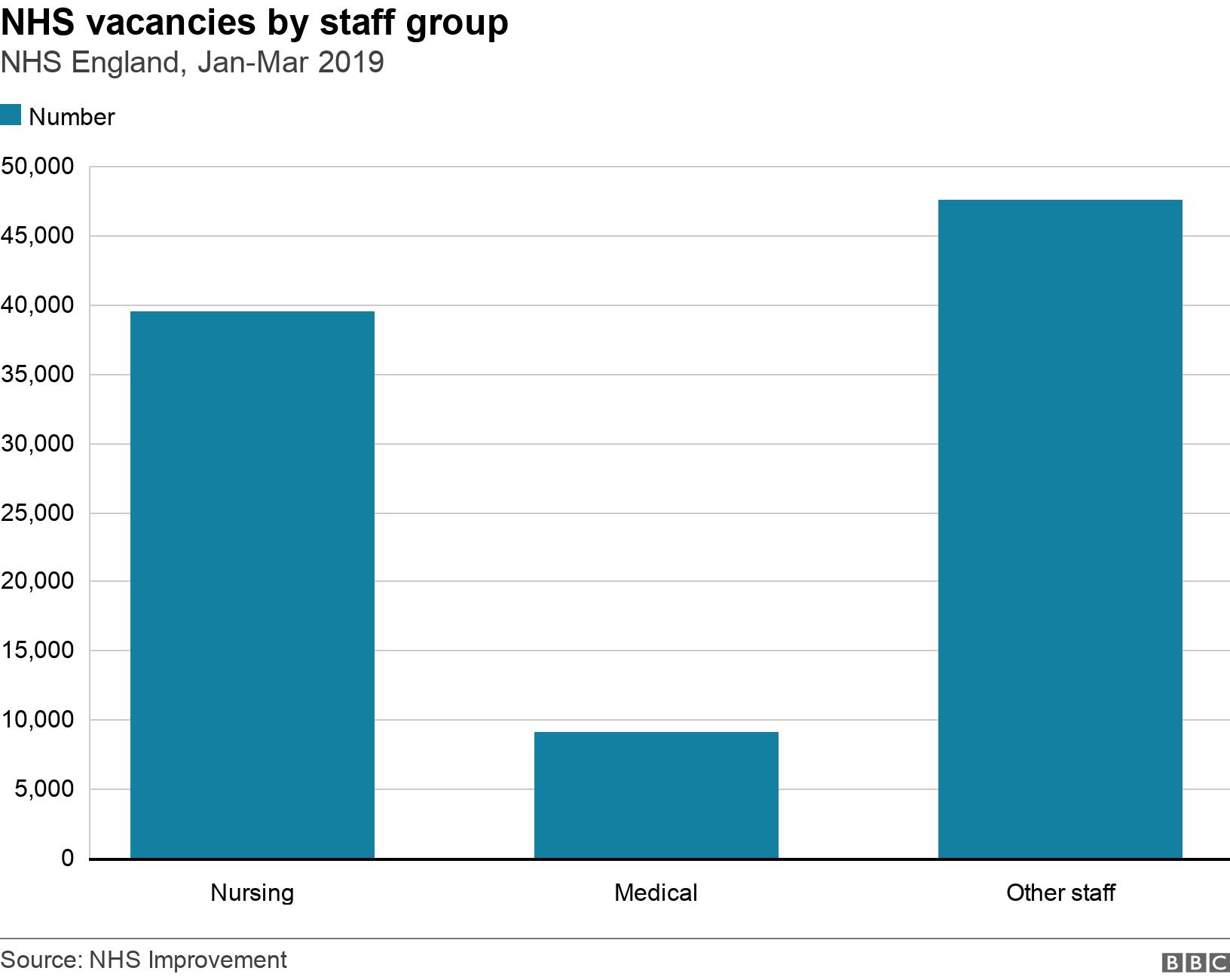

Another thorny issue is the workforce challenge. One in 12 posts in the NHS is unfilled.

The government is already increasing the number of doctors and nurses in training, but it will be many years before the full impact of that is felt.

Instead, immediate attention is turning to retaining more nurses - every year more than 30,000 leave the NHS - and international recruitment.

The number of staff coming from the EU has fallen since the referendum.

Ministers are proposing a fast-track visa application system, but whether it will be enough to help fill the vacant positions and grow the workforce remains to be seen.

There is also more work needed to resolve the pensions dispute that has prompted some doctors to stop doing extra shifts after they were landed with large tax bills (because the threshold at which tax kicks in on pensions was lowered).

NHS England has offered to pick up the bill until April 2020. But a more sustainable solution needs to be found. And quickly.

Hospital bosses say it is one of the major reasons waiting lists for routine treatments are going up.

Getting children vaccinated

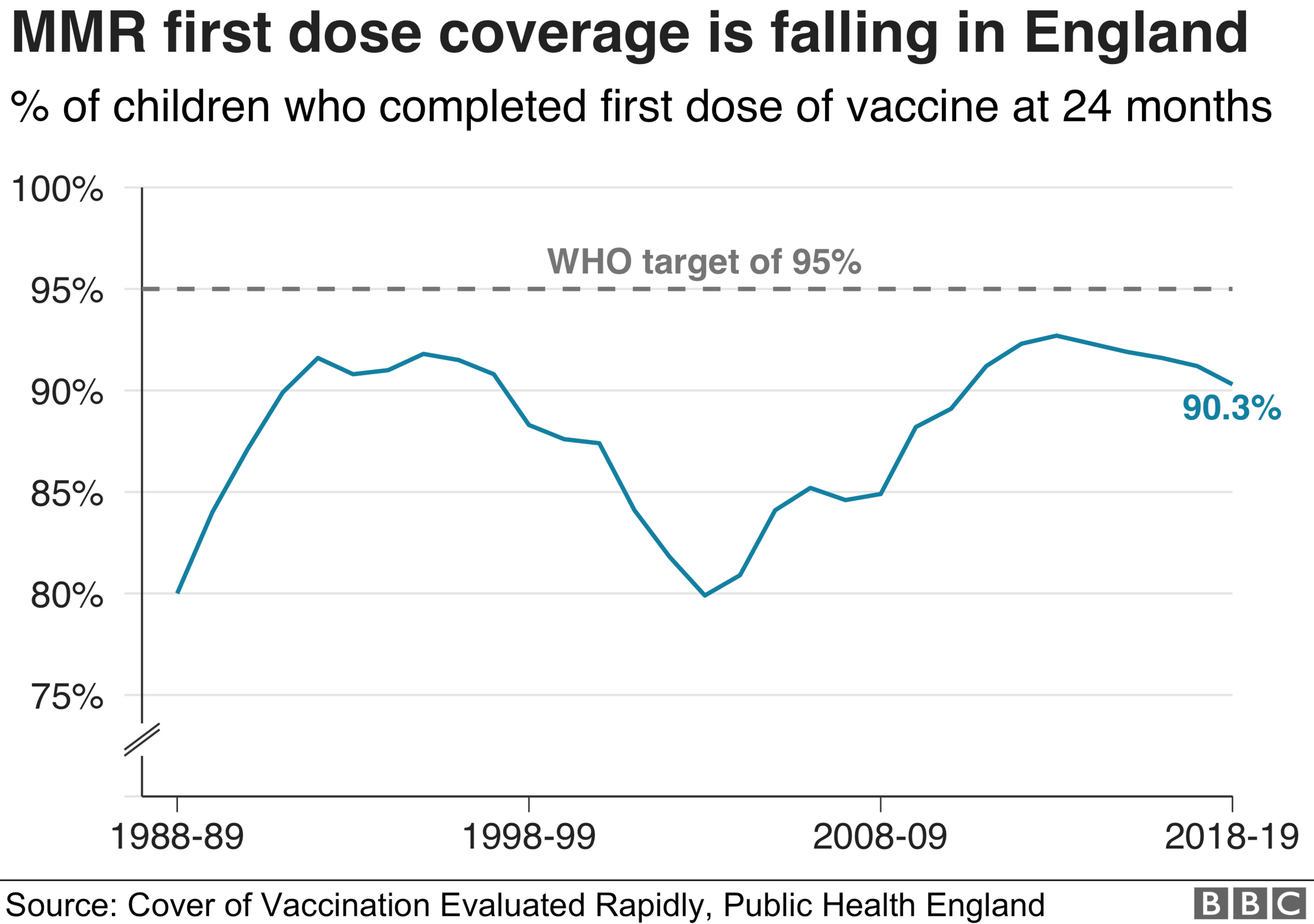

In September, NHS figures showed that coverage for all 10 routine childhood vaccinations for the under-fives had fallen in the past year.

It was the fifth year in a row that uptake had gone down for the MMR (measles, mumps, rubella) vaccine.

Health officials warned that children were being put at risk of deadly infections by the decision to shun the immunisations.

It came after the UK was stripped of its measles-free status by the World Health Organization in the summer.

Ministers are already looking for a solution, with Health Secretary Matt Hancock saying he is considering compulsory vaccination.

Many health experts doubt this will be effective - and instead have called for the NHS to ensure vaccination clinics are more accessible, with some suggesting they should be offered in locations such as supermarkets.

A new vaccination strategy was expected to be published in the late autumn, but that was delayed when the election was called.

Agitation will start to grow if it is not published soon.

- Published4 August 2019

- Published6 January 2019

- Published8 February 2017

- Published8 February 2017

- Published6 January 2017