Coronavirus: Is the NHS ready for the surge in cases?

- Published

- comments

The NHS is braced for a surge in coronavirus cases.

Experts are predicting they will soon start rising rapidly before the impact of curbs on everyday life kicks in and starts, with luck, to suppress the outbreak.

So what has been happening and will the NHS be able to cope?

Hospitals have cleared the decks

From 15 April, all routine operations, such as hip and knee replacements, are being cancelled for three months.

There is also a drive to get as many patients as possible who do not need to be there, discharged from hospital.

On 27 March, the head of the NHS in England, Sir Simon Stevens, said: "We have reconfigured hospital services so that 33,000 hospital beds are available to treat further coronavrius patients."

NHS bosses have asked hospitals to protect cancer care, although in some places the rising numbers of coronavirus cases has meant services have been hit.

For example, the Barking, Havering and Redbridge NHS Trust has said it would only be able to carry out urgent operations in the coming weeks.

Intensive care capacity is increasing

The NHS had over 4,000 intensive care beds at the start of March with around four in five occupied.

But since then work has gone on to increase supply.

Health Secretary Matt Hancock said this week that more than 2,500 extra critical care beds had been made available (not including those in temporary hospitals).

A deal has already been done with the private sector to get access to 1,200 ventilators used in their hospitals, while ventilators for children are being repurposed and theatre ventilators that are no longer needed for routine surgery are being used as well.

It means there are around 8,000 ventilators in use currently.

But thousands more have been ordered from existing suppliers, while Dyson has agreed to try to make 10,000 for the NHS although it could be months before these are available.

How they will be staffed remains unclear. Rules are being relaxed to allow non-intensive care specialists to be paired with specialists, and staff-to-patient ratios may also need to be reduced.

What do I need to know about the coronavirus?

EASY STEPS: What can I do?

CONTAINMENT: What it means to self-isolate

MAPS AND CHARTS: Visual guide to the outbreak

VIDEO: The 20-second hand wash

Big field hospitals are being set up

Timelapse captures the transformation of London's ExCeL centre into the Nightingale Hospital

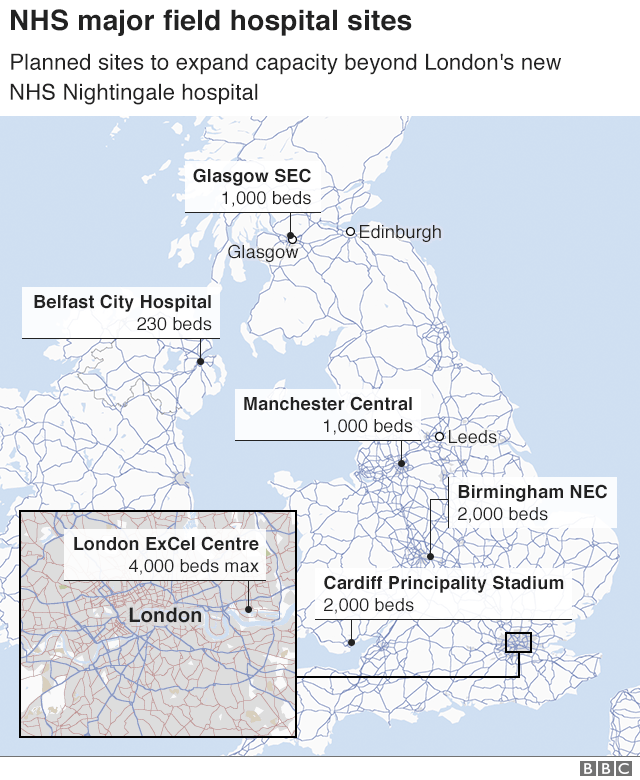

A field hospital at the ExCeL Centre in east London opened on Friday, and will eventually hold up to 4,000 patients.

The exhibition space, which has been used in the past for events like Crufts and Comic Con, was converted into a hospital in only nine days.

Dubbed the Nightingale Hospital, the temporary base is being staffed by NHS medics with the help of the military.

It will initially provide about 500 beds equipped with ventilators and oxygen.

Another temporary hospital, at the National Exhibition Centre in Birmingham, with a capacity for 5,000 beds, will open on 12 April.

A 1,000-bed facility at the Manchester Central Conference Centre (formerly the GMEX Centre) will also open in mid-April.

Temporary hospitals are also being set up around the UK in Glasgow's Scottish Events Campus, Cardiff's Principality Stadium and Belfast City Hospital's tower block. Two more have been commissioned for Bristol and Harrogate.

Retired staff and volunteers helping out

Ministers have appealed to retired staff to come back and help the NHS.

Legislation has been passed reducing the regulatory hurdles they need to go through to return to work.

About 20,000 former staff in the UK have come forward, while more than 18,700 student nurses and 5,500 final year medics will also join the NHS workforce.

Health Secretary Matt Hancock has also put out a call for 250,000 NHS volunteers to deliver food and medicines. Within days 750,000 people had come forward to offer their services.

The main focus of their work will be supporting the 1.5m highly vulnerable people who have been told to shield themselves from any contact with others.

NHS England medical director Stephen Powis says there have been "outbreaks of altruism" and he feels "bowled over" by the responses from retired staff and the public.

Problems remain

One of the reasons retired doctors and nurses are being recruited is because of the need to cover staff who are off sick themselves.

Hospitals have been reporting that large numbers are having to self-isolate at home because they fear they have the virus, or a member of their household does.

The government has said "a significant number" of NHS workers are taking these measures but is not giving a percentage.

One of the problems is that many health staff have found it difficult to get tested. The government's testing strategy has focused on screening seriously ill patients in hospital with coronavirus symptoms.

But Cabinet Office minister Michael Gove says "the absolute, top priority" now is testing doctors and nurses in hospitals and those working in social care.

The government says more than 7,000 NHS staff have been tested so far.

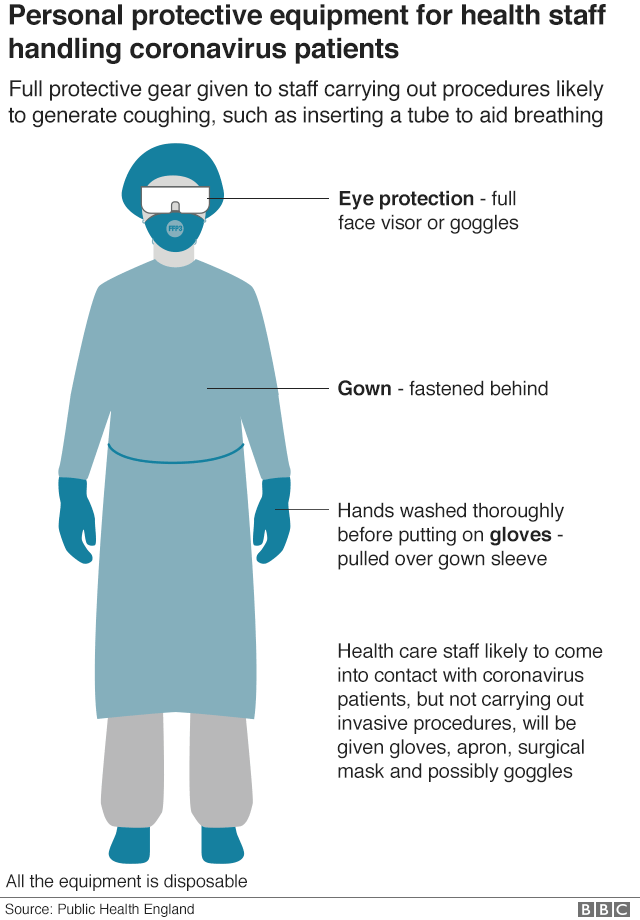

But perhaps the biggest concern has been the lack of personal protective equipment in individual hospitals - masks, gowns and gloves - to prevent staff being infected.

British Medical Association leader Dr Chaand Nagpaul said the situation was "totally unacceptable" and was putting the health and lives of staff at risk.

Ministers have acknowledged there have been distribution problems, but said a national supply team, supported by members of the armed forces, had been "working around the clock" to deliver equipment.

The government said on 1 April that in the previous two weeks, 390m pieces of protective equipment had been delivered to the NHS, including 600,000 high-grade filtration masks and nearly 4.2m surgical masks.

So can the NHS cope?

The driving force behind the government's measures to suppress the spread of coronavirus - including closing down schools, restaurants, theatres and pubs - has been the need to stop the health service becoming overwhelmed.

The key piece of modelling that influenced the government, external was done by Imperial College London, which warned that the previous strategy, aimed at only slowing the spread of the virus, risked hospitals getting swamped. It said that 250,000 lives would be lost in the process.

Prof Neil Ferguson, one of the lead researchers, has said he is "reasonably confident" that hospitals and, in particular intensive care units, could cope given the increase in ventilators and change in policy by ministers, although local areas could struggle. UK chief medical adviser Prof Chris Witty said it was "probably manageable".

But not everyone agreed. Prof Hugh Montgomery, an intensive care specialist at University College London, said he had "no doubt" hospitals would fail to cope., external

He said there would be a "tsunami" of cases coming in the next two weeks in London, and predicted units would start running out of beds.

Chris Hopson, chief executive of NHS Providers, which represents hospitals, said that at this stage, no-one could say for sure what would happen overall, but added that the health service had put itself in the best position possible, having "never done so much in such a short space of time".

With experts predicting the peak in a matter of weeks, we will soon find out.

- Published4 August 2019

- Published6 January 2019

- Published8 February 2017

- Published8 February 2017

- Published6 January 2017