Coronavirus: What are ventilators and why are they important?

- Published

The government has said it will buy thousands of ventilators to help ease the pressure on hospitals caused by the coronavirus crisis.

For patients with the worst effects of the infection, a ventilator can offer the best chance of survival.

What is a ventilator and what does it do?

Simply put, a ventilator takes over the body's breathing process when disease has caused the lungs to fail.

This gives the patient time to fight off the infection and recover.

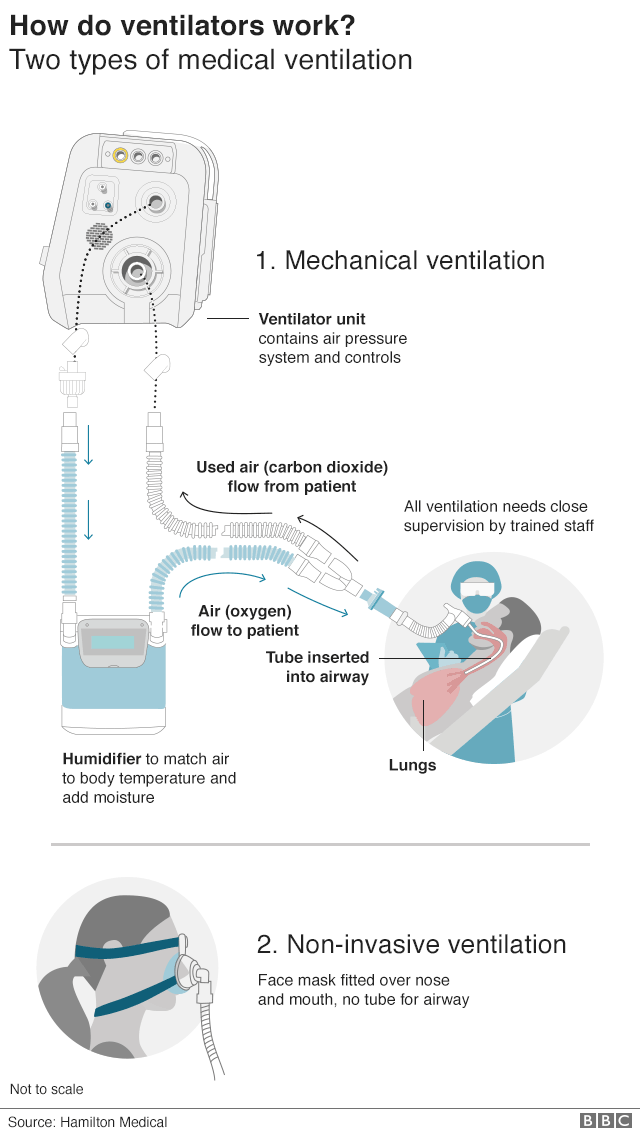

Various types of medical ventilation can be used.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), some 80% of people with Covid-19 - the disease caused by coronavirus - recover without needing hospital treatment.

But one person in six becomes seriously ill.

In these severe cases, the virus causes damage to the lungs, causing the body's oxygen levels to drop and making it harder to breathe.

To alleviate this, a ventilator is used to push air, with increased levels of oxygen, into the lungs.

The ventilator also has a humidifier, which adds heat and moisture to the air supply so it matches the patient's body temperature.

Patients are given medication to relax the respiratory muscles so their breathing can be fully regulated by the machine.

All medical ventilation requires close supervision from trained staff

People with milder symptoms may be given ventilation using facemasks, nasal masks or mouthpieces which allow air or an oxygen mixture to be pushed into the lungs.

This is known as "non-invasive" ventilation, as no internal tubes are required.

Another form of ventilation - continuous positive airway pressure or CPAP - keeps a patient's airways continuously open,

Early reports from Lombardy in northern Italy suggest about 50% of patients given CPAP have avoided the need for full mechanical ventilation.

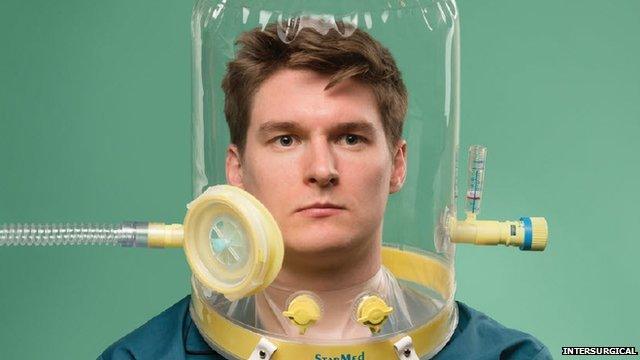

A type of CPAP ventilation using a hood, where pressurised oxygen is pumped in via a valve, reduces the risk of airborne transmission of the virus.

Oxygen hoods reduce the risk of disease transmission

Intensive Care Units (ICUs) would generally put patients suffering acute respiratory distress on mechanical ventilation quickly, to ensure oxygen levels in the body stay normal.

However Dr Shondipon Laha, from the Intensive Care Society, told the BBC that unless they become seriously ill, most patients with Covid-19 would not need a mechanical ventilator and could be treated at home or with supplementary oxygen.

Although there were risks when using ventilators, such as not knowing who would suffer long-term effects, he said, sometimes a ventilator was "the only way of getting oxygen into the patient".

Another issue, Dr Laha explained, was having enough trained staff to operate the ventilators correctly.

How many ventilators does the UK have - and how many might we need?

The UK is understood to currently have about 10,000 ventilators having added to the previous stock of just over 8,000 by increasing production and sourcing other machines from overseas.

A number of ventilators have also been acquired from private hospitals.

Health Secretary Matt Hancock has said the country needs 18,000 machines for when the virus peaks, down from an original estimate of 30,000.

Mr Hancock told the BBC's Andrew Marr programme on 5 April that projected demand had come down because social distancing measures were working.

The exact type of extra ventilators needed, and who makes them, is still being finalised.

The delay is linked to a changing understanding of how to treat patients requiring ventilation, external, according to the Financial Times.

The Smiths ParaPac ventilator is designed to be easily transported

A consortium of UK manufacturers is leading efforts to produce a version of a machine built by Oxfordshire company Penlon. On 16 April, it was announced that the Penlon Prima ESO2 devices had been approved and that hundreds are expected to be built for hospitals over the next week. By the start of May, it is hoped that 1,500 a week will be made.

As part of that same initiative, the first ventilators - portable ParaPac devices from Luton-based firm Smiths - have been delivered to wards over the last few days.

The consortium includes Airbus, Rolls Royce and a number of Formula One racing teams.

A separate machine being designed and built from scratch by Dyson is also being considered by the government.

Production of other types of non-invasive ventilator is also being scaled up, with a government order of some 10,000 Ventura CPAP devices designed by University College London Engineers with industry partners Mercedes-AMG-HPP.