Coronavirus doctor's diary: Why does Covid-19 make some healthy young people really sick?

- Published

Dr John Wright of Bradford Royal Infirmary tells the story of an 18-year-old, whose experience shows that Covid-19 can seriously affect even healthy young people.

One of the biggest mysteries about Covid-19 is why some people who shouldn't really be harmed by it very much at all get really sick, and end up in hospital.

Someone who is elderly or who has certain pre-existing health problems - heart disease or diabetes, for example - is clearly at higher risk. Obesity is also a big disadvantage.

But occasionally we see a young person who is otherwise in good health becoming very ill. Eighteen-year-old Marium Zumeer, for example. It was her first time in a hospital when she was brought in by ambulance, struggling to breathe and with pains in her chest.

She was unable to speak in full sentences, says respiratory consultant Dinesh Saralaya, and was so distressed and agitated that she initially refused non-invasive ventilation with oxygen (CPAP). She might have had to be sedated and intubated in the Intensive Care Unit, but first Dinesh made a video call to Marium's father, Kaiser, a Bradford taxi driver.

"When they told me they were taking her to ICU, I couldn't feel my legs. I thought I was going to collapse, I was so shocked," he says. "I begged them to just try something."

A SIMPLE GUIDE: How do I protect myself?

IMPACT: What the virus does to the body

RECOVERY: How long does it take?

LOCKDOWN: How can we lift restrictions?

ENDGAME: How do we get out of this mess?

Dinesh was himself keen for Marium to become part of the recovery trial, meaning that she would be randomly allocated either a placebo or one of four drugs that it's thought may be helpful for people suffering from Covid-19. He made clear, though, that Marium would have to give CPAP another go.

Kaiser then spoke to Marium.

"These words that he said to her will always ring in my ears. He told her, 'Please take part and help the wider community, not only yourself.' And she was in tears and so unwell, and then she heard this from her father and she signed the consent forms," Dinesh says.

He was overjoyed when the drug Marium was allocated turned out to be one that he already knew had been having very good results, the steroid dexamethasone.

"I couldn't control my excitement actually. I went back to her and said, 'You are going to be on this and you will get better, mark my words.'"

We always ask our patients how they think they've caught Covid-19. For the most part, there's a clear story of contact with someone with symptoms, a household member or an occupational exposure. However, there are a surprising number of patients where the source is an enigma.

It's so important to keep washing our hands and avoid touching our faces. Even a quick rub of our eye may be enough to transmit infection.

If you're going to get infected, then you need a proper dose of the coronavirus. There's an explosion of experimental research about the number of viral particles needed and how these are spread by air and from surfaces. A single breath releases hundreds of tiny droplets but these don't travel far. A cough or sneeze, by contrast, can release hundreds of millions of droplets and these go everywhere.

In outdoor environments, these are rapidly dispersed. And with the help of a bit of sunlight, the risk of infection is low. Hence our national guidance to encourage outdoor activities. Indoors is trickier, particularly when ventilation is limited. Anywhere that people are closely packed, talking, singing, hugging, touching, these will all be right for outbreaks. The duration of exposure is also important. The longer the time exposed, the greater the risk.

As a taxi driver, Kaiser could have been infected by a client - but he had stopped working.

In fact, he was so worried about protecting his elderly parents from Covid-19 that he took his children out of school a week before the lockdown. So how might they have become infected?

Front line diary

Prof John Wright, a doctor and epidemiologist, is head of the Bradford Institute for Health Research, and a veteran of cholera, HIV and Ebola epidemics in sub-Saharan Africa. He is writing this diary for BBC News and recording from the hospital wards for BBC Radio.

Listen to the next episode of The NHS Front Line on BBC Sounds or the BBC World Service

Or read the previous online diary entry: The drug combination that may help us beat Covid-19

Mostly the family stayed at home, only going out for shopping, but Kaiser's mother needs kidney dialysis, so three times a week he would drive her to Bradford Royal Infirmary.

And there was one other occasion when they all left the house - for a funeral.

"It was for a first cousin, who was only 23 and had been in an accident. We went to Sheffield just to pay our condolences," Kaiser says.

Kaiser says no-one else at the funeral got ill, so it's impossible to say with confidence that that is where the family picked up the virus.

What is clear, though, is that eventually the whole family became ill. In fact, shortly after Marium was brought to hospital, her 84-year-old grandfather, Mohammed, arrived in another ambulance, followed later by her mother, Saiqu.

Tragically, Mohammed, who came to the UK from Pakistan in the 1960s to work in the textile mills, did not recover. His loss was particularly significant for the family, because he was helping to bring up the children of Kaiser's brother, Manir, who died three years ago.

"He said his goodbyes. I said to my dad that he was going to be seeing his dead son and that he was going to be reunited with him. I said to give him hugs and kisses from me, to tell him that we're all thinking about him," Kaiser says.

"I said to my dad that we loved him dearly and I just reassured him and said what a wonderful man he was. I said I was so proud of him, that he was the best dad in the world, that I couldn't ask for any more and that he'd done so much for us throughout our lives.

"He suffered when he was young, he'd had a hard life and had always grafted. He worked so hard for all of us."

But Kaiser decided to keep the news of his father's death from Marium, for fear that the distress would be bad for her health.

And in fact both Marium and her mother got better quite quickly.

Dinesh Saralaya kept a close eye on Marium. Having initially needed a high volume of oxygen, after a few days she was already feeling a lot better and could be taken off the CPAP ventilation.

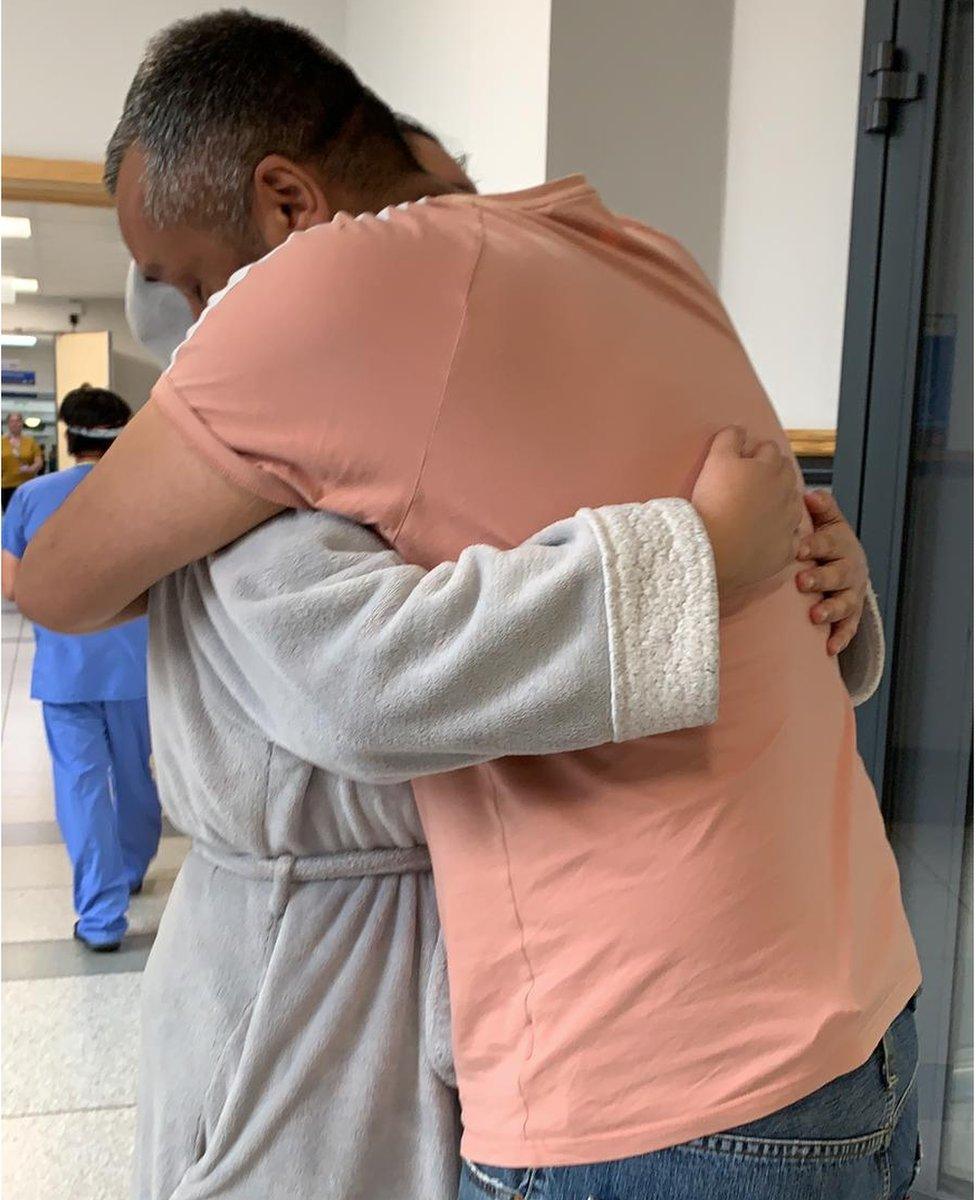

Then, after a few more days, Dinesh went to see her again and they called Kaiser - an emotional moment that Dinesh says he will never forget.

Not long after that, Marium was discharged. She's one of 450 patients successfully treated at Bradford Royal Infirmary.

It was then that Marium learned about her grandfather's death.

"I told Marium as soon as we got home. It was one of the hardest things I've had to do. It was eating away inside of me, to be honest," Kaiser says. "If I could have gone to the hospital and been with her, I would have broken the news straight away - you need to be able to put an arm round someone and comfort them when you tell them. And I was worried that had I told her when she was so ill herself it might have set back her recovery."

Marium's last conversation with her grandfather was over Facetime as she lay in one ward, and he in another. As they were talking, he got up and smiled, she says.

"I'll always carry that memory with me. He had an oxygen mask on, so I was just thinking that he's not well and he's got an oxygen mask on. I didn't know that he was going to pass away a couple hours after me speaking to him."

Like us, she is puzzled about why she got so much sicker than her five siblings.

"I think young people don't realise this can happen to them. I didn't think it could happen to me," she says. "You don't see it coming, it is just there and suddenly it can take you and leave you so ill."

She is planning on going to university in the autumn and imagines that many other teenagers about to begin their lives as students - in halls of residence, lecture rooms, libraries and cafes - will be as unaware as she was of the possible risks.

But she is also drawing some positives from the experience.

"This whole thing has made me stronger. You really learn the value of true life - you know, that every breath is vital and so important. Just to be sitting here right now, every breath I take, I'm so grateful for it."

Follow @docjohnwright, external and radio producer @SueM1tchell, external on Twitter