Fergus Walsh: The mental health crisis looming in ICU

- Published

The BBC's Fergus Walsh meets medics treating patients with Covid-19 at University College Hospital London

I am still haunted by what I saw in intensive care during the peak of the coronavirus pandemic.

The patients on ventilators, motionless except for the rise and fall of their chest, their bodies connected to monitors and drug infusion pumps. An unconscious existence balanced between life and death. The calm of the staff, in full PPE, working as one unified team to deal with this completely new viral menace, the chaos of Covid-19. No-one had experienced anything like it before.

At the time, and in every subsequent conversation I've had with intensive care staff, I've been struck by their dedication to their work, but also by their openness regarding the toll it is taking on their mental health - anxiety, frustration, insomnia, fear, exhaustion.

For much of society, the emphasis is on coming out of lockdown: meeting with friends outside, support bubbles, shops reopening.

So there is a sense that the threat, although still there, is receding. At one point there were more than 3,000 Covid patients on ventilators across the UK. Now it is well under 500. But that still means intensive care staff are donning PPE for every shift. For them, the threat is still as tangible as ever.

I spoke to some ICU nurses at Homerton hospital in north-east London about their experiences of the pandemic and how they are feeling now they see life outside beginning to return to a new normal.

'Deep inside, I'm broken now' says ICU nurse Alfred Batalla

Alfred Batalla, 31, is a senior staff nurse - he's from the Philippines.

"My mental health was quite good, but this really shook me up," he says. "During the peak I was having anxiety moments and panic attacks. I would wake up dreaming about work.

"I'm like the happiest person, on the outside it seems like I'm always joking around. But deep inside I'm broken now because of this."

Alfred has been seeing a psychologist at the Homerton on an informal basis, which has helped. But he also wanted a different kind of therapy, so asked the hospital to bring in a dog. The charity Pets As Therapy has had to suspend all visits during the outbreak but a couple of staff brought in their own dogs so that ICU staff could spend time with them after their shift.

The hospital also created a "wobble room" where staff could relax.

Alfred Batalla found pet therapy helped with the stress

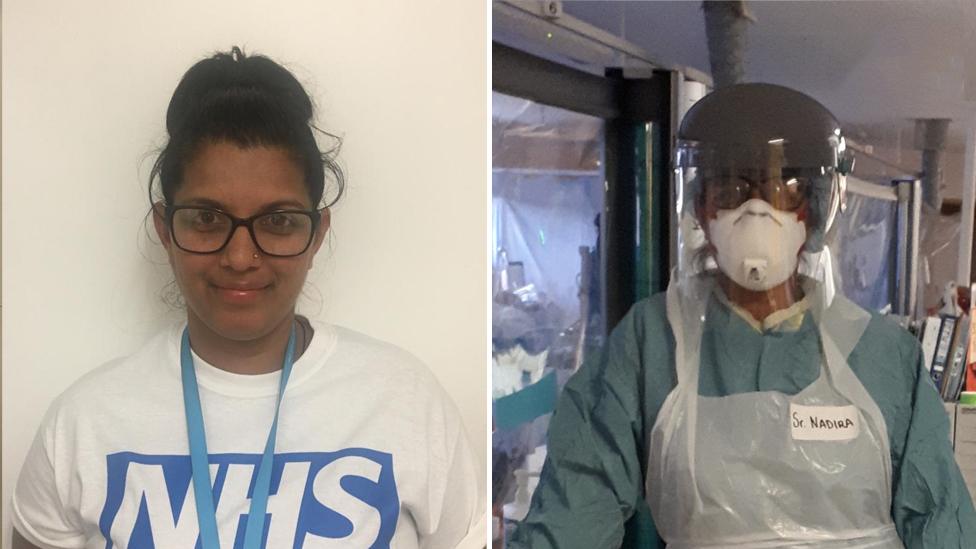

Senior sister Nadira Balkissoon, 42, is originally from Trinidad but has been living in the UK for more than 20 years. A single mum, she sent her two daughters to stay with their grandparents when coronavirus struck.

"I had to send them away, because I was worried that I could infect them," she says.

"I didn't see them for 10 weeks. I spoke to them every day, but the more I saw them from a distance, the more upset it made me.

"I never prayed so much as I did in those 10 weeks. I've never seen people die so quickly, I've never seen an infection take a toll on a human being as quickly as it did.

"And these were young people, fairly close to my age. I was very, very scared. I had panic attacks just like Alfred did."

That fear is something they all felt.

"We had 31- and 35-year-old patients who had been fit and well, and they died," says Alfred. "And that made me think: 'I could be in that bed with Covid and dying.'"

Two nurses and a doctor at Homerton hospital died after contracting coronavirus, although none of them worked in critical care. They included Dr Abdul Mabud Chowdhury, a consultant urologist who warned about a lack of PPE for NHS workers.

Now that lockdown is easing, they are apprehensive.

"I think we're all anxious, we're all holding our breath, and praying there isn't a second wave," says Nadira. "But we did learn a lot from this experience and would definitely be better prepared."

Nadira's girls are back home now - it was an emotional reunion.

"I'm an emotional person by nature so they were expecting tears. But I kept staring at them: for the first couple of days, all I did was just look at them. They thought it was weird but they couldn't understand what I had experienced," she says.

As the BBC's medical correspondent, since 2004 I have reported on global disease threats such as bird flu, swine flu, Sars and Mers - both coronaviruses - and Ebola. You could say I've been waiting much of my career for a global pandemic. And yet when Covid-19 came along, the world was not as ready as it could have been. Sadly, we may have to live with coronavirus indefinitely. Here, I will be reflecting on that new reality.

More from Fergus:

Lucy Jenkins, 37, is matron on the intensive care unit. She's married to a paramedic and they have two young children. She recalls the end of one long shift earlier in the crisis and her 45-minute journey home to Essex.

"I got in the car and I just sobbed the whole way home because I was scared," she says. "Scared for my staff, scared for me, scared for my husband, scared for my kids, and I couldn't see how we would go back to normal."

In some ways though, she thinks things are tougher now, even though they have gone from a peak of 30 Covid patients in intensive care down to two.

"When we were in the surge, and crisis-managing, you just got on with it, there was no choice. The adrenaline kept you going. Now everyone's hit a bit of a wall. Nobody knows what 'normal' is going to look like, and that is emotionally exhausting," she says.

"I think there's a huge risk that our staff are going to burn out and this is the time we have to get it right. We could potentially lose some really good ICU nurses because of what they've experienced."

During the crisis, the Homerton held drop-in meetings for ICU staff to talk about their experiences. They were led by psychiatrist Dr Hugh Grant Peterkin, who would meet doctors and nurses as they came off shift at 8am.

"I was moved, one time close to tears, talking with them all," he says.

He is concerned colleagues might develop psychological difficulties due to what they experienced, but he is also wary of saying it will inevitably lead to negative psychological consequences.

"There's a real sense of what people have been through, so I think there could also be a renewed sense of purpose, camaraderie and connectedness," he says.

"I think the flip-side is that people are knackered. There's a degree of exhaustion that is unprecedented in my experience."

40,000 DEATHS: Could they have been prevented?

TESTING: Who can get a test and how?

LOOK-UP TOOL: How many cases in your area?

EUROPE LOCKDOWN: How is it being lifted?

TWO METRES: Could less than 2m work?

THE R NUMBER: What it means and why it matters

Even before the pandemic, wellbeing was already a concern in ICU, with one in three staff considered to be at high risk of burnout, external and critical care nurses especially affected.

Clinical psychologist Dr Julie Highfield is Director of Wellbeing at the Intensive Care Society, external and she's leading a national project to provide mental health support to all ICU staff. She says they have been suffering from a kind of "low level, constant trauma" - and that people found it particularly hard not to be able to involve patients' relatives in their last days of life.

"We know from other pandemics that the psychological needs of staff slowly emerge," she says. "So there's the initial stress, but over time, people slowly start to change the relationship with the job - they become more avoidant, exhausted and flattened in mood. And that's the thing we're quite worried about.

"When life for the UK goes back to normal, it won't go back to normal for healthcare professionals who will be left with long-lasting impacts."

At some point, perhaps when we have a vaccine, we will hopefully move into a post-coronavirus world. Until then, hospitals will need to divide their care between Covid and non-Covid areas. Spare a thought for those critical care staff destined to spend every working day in full PPE for the foreseeable future. The clapping for carers has stopped, but the impact on staff will continue long into the future.

Follow @BBCFergusWalsh, external on Twitter