Coronavirus: Would you spit in a tube every week to end the pandemic?

- Published

What if there was a way of returning life to what it was like before coronavirus? No more social distancing, no face coverings, no fear of Covid-19. Of course the reason for all the restrictions is an attempt to bear down on the virus, and to minimise its spread. What we need is a fast and reliable way of spotting those around us who are infected.

The first problem is that fewer than one in four people testing positive for coronavirus have symptoms on the day they get tested.

That highlights the risk of the virus being spread by people who aren't aware they are infected.

The second issue is the test itself. The current gold standard means of detecting coronavirus involves a swab of the back of the throat and up the nose. Maybe I'm unduly sensitive but I found sticking the long cotton bud around my tonsils and up my hooter a bit unpleasant, making me retch. It's all over in a couple of seconds, but I'm not sure I'd want to have it done every week, as has been proposed for NHS front-line staff.

A third problem is time. The swab, or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test has to be sent to a lab and takes a few hours to process. Nine out of 10 people who attend one of the drive-in centres get their result back within 24 hours. But it's not yet a while-you-wait service.

So what we need is a rapid, easy and reliable test for coronavirus.

Some fast-turnaround swab tests are being trialled, which would be a big step forward.

But saliva tests could be a real gamechanger, external.

Imagine if all you had to do was spit into a tube to find out if you have coronavirus.

OK, it's not quite as simple as that. The saliva sample has to be sent to a laboratory, but the result can be turned around far quicker than a swab test.

Jayne Lees and her family are part of a four-week trial of saliva tests under way in Southampton.

I watched as Jayne and her three teenage children, Sam, Meg and Billy, sat round their kitchen table, spat on a spoon and tipped the spit into a test tube.

"A swab test feels quite invasive, especially if you are not feeling very well," says Jayne. "The saliva test is so much easier."

More than 10,000 GP and other key workers and their families in the city are involved in the project.

"We think saliva is a really important fluid to test," says Keith Godfrey at the University of Southampton, who is helping to co-ordinate the trial, external.

"The salivary glands are the first place in the body that the virus infects. It seems people become positive in their saliva before the rest of their breathing tubes.

"If we are seeking to pick up people in the early course of the infection, this may be the way forwards."

The success of the trial depends on how accurate the saliva test is at detecting coronavirus.

The samples from the Southampton study are being processed at the Animal and Plant Health Agency government laboratories in Surrey. The samples are added to a solution and heated to release the genetic material of the virus. The method, known as RT-Lamp, takes around 20 minutes, compared to several hours for PCR testing.

"We are very excited," says Prof Ian Brown, head of virology. "We had some major breakthroughs in the past few weeks, in terms of overcoming technical challenges in being able to use the saliva test."

This is where things get interesting. If the pilot trial goes well, the entire city of Southampton, more than 250,000 people, could be offered weekly saliva tests.

"If we're looking to reopen society and the economy, this may be a way of monitoring the presence of the virus in communities and picking up outbreaks before lockdowns are needed," says Prof Godfrey.

The whole of the UK could be offered weekly spit tests

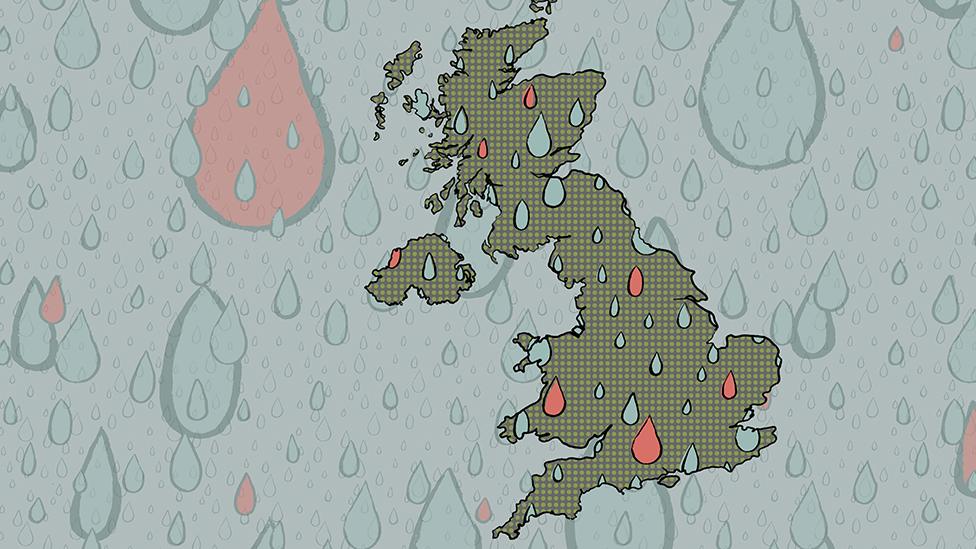

Some would like things to go even further. A group of scientists led by Prof Julian Peto of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine suggests that the entire population of the UK should be offered weekly spit tests, external for coronavirus.

They argue that the Covid-19 epidemic could be "ended and normal life restored" if mass surveillance was carried out. This would mean a huge ramping up of laboratory testing. Currently the government says it can carry out 300,000 tests a day, but that would need to rise to 10 million a day.

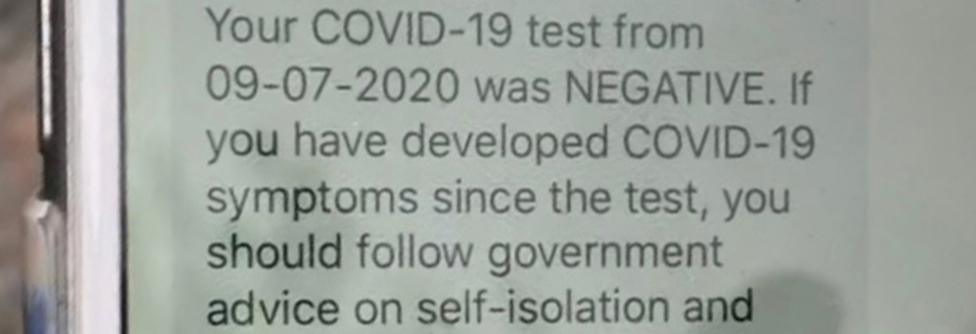

The way it would work is this: you do your spit test and send it off. Within 24 hours you get a text with the result. If it's positive then you and your family have to self-isolate. Restaurants and other public venues could ask for evidence of a recent negative test before allowing people entry. The hope is that early identification of those infected would rapidly bring the epidemic to a halt.

Of course it would be expensive, perhaps £1bn per month. But that is a tiny fraction of the impact of coronavirus on the economy. The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) suggests the crisis is likely to cost more than £300bn in this financial year, and perhaps even more.

Compliance would be an issue. How many of us would be prepared to spit in a tube every week? It would be a faff. But if the flip side was that all social distancing could be ended, wouldn't you jump at the chance?

As the BBC's medical correspondent, since 2004 I have reported on global disease threats such as bird flu, swine flu, Sars and Mers - both coronaviruses - and Ebola. I've been waiting much of my career for a global pandemic, and yet when Covid-19 came along, the world was not as ready as it could have been. Sadly, we may have to live with coronavirus indefinitely.

If it worked it would mean an end to face masks and one-way systems in shops, an end to isolation for millions of elderly and vulnerable people. You could hug your friends and grandparents again.

Something less ambitious but more targeted could also have a major impact. Schools could test pupils and staff on a weekly basis. Regular spit tests could also be performed in care homes or in hot spot areas. Labs could be set up in airports, so that arriving or departing passengers could be tested while they waited.

A lot is riding on the Southampton trial. One issue which may complicate things is that the incidence of coronavirus in the city has been falling. Jayne Lees and her family have twice tested negative so far. I suspect the same applies to all, or nearly everyone else taking part.

In order for the study to work, it needs to be able to identify positive samples as well as negatives.

But Jayne's children are among those hoping such hurdles will be overcome and mass saliva testing becomes the solution.

"It would be great, we could get the pandemic over and done with," says Sam, 19. "It would change people's lives."

Follow @BBCFergusWalsh, external on Twitter

SOCIAL DISTANCING: What are the rules now?

YOUR QUESTIONS: Our experts have answers

LOOK-UP TOOL: How many cases in your area?

THE R NUMBER: What it means and why it matters