Coronavirus testing: What's going wrong?

- Published

People queue for tests in Southampton

People up and down the country have been blocked from getting coronavirus tests in recent days, as appointments were paused with the system struggling to cope. Yet the government says capacity is higher than ever.

So what's going on in the UK's testing system?

Rising demand

Demand for tests has soared, no-one disputes that. What isn't clear is by how much. It's hard to know exactly - the figures aren't capturing all the people who've tried to book and haven't been able to get a test.

The combination of people returning from holiday and children going back to school will have put pressure on the system. And early autumn will have brought other respiratory viruses, with symptoms similar to coronavirus - perhaps especially in children.

For many, the message that it's essential to get a test if you have symptoms, will have sunk in. Dozens of people have told the BBC of doing so out of a feeling of civic duty.

It's something the government appears to have "underestimated" the impact of with the rise in cases also coming sooner than thought, says Sir John Bell, of Oxford University.

At the same time, sources have expressed concerns about the "worried well" - people applying for tests even if they don't have the relevant symptoms. Health Secretary Matt Hancock has claimed a quarter of people wanting tests do not have symptoms, and so are ineligible. When this was queried, the government said this figure was not a formal count.

But it has pointed to reports of whole school year groups being told to get tested, and people asking for tests before and after going on holiday.

Empty drive-throughs

There is no shortage of swabs, testing centres and staff. There are almost 400 testing centres in total across the UK, including drive-through and walk-in sites, mobile units set up in hotspots and satellite sites at hospitals and care homes.

But getting an appointment at one of these has been a challenge, even though pictures have emerged of sites with hardly any people getting tested.

Limited lab capacity means the releasing of new appointments is being held back. That's because once you take a swab, there's a narrow window of time to process it in before it becomes invalid. If the labs can't get to it in time, because they are dealing with yesterday's tests, that swab will be wasted.

So when labs get behind, there's no point opening up new appointments to test people.

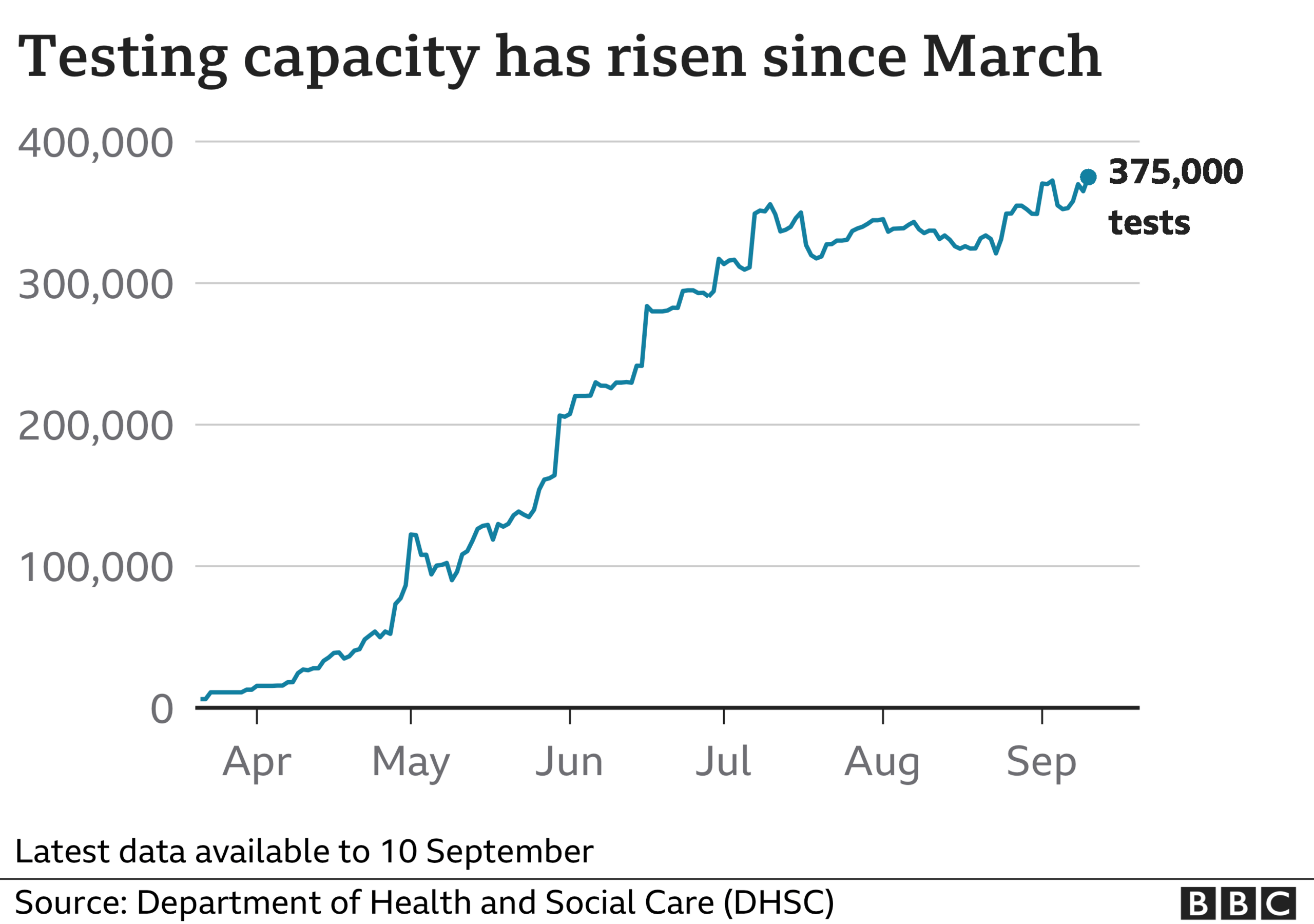

Testing capacity is rising

The government says testing capacity - which it defines as how many can be processed in the lab each day - is higher than ever. This is true. The capacity has grown rapidly, with latest figures showing nearly 375,000 tests a day can be processed.

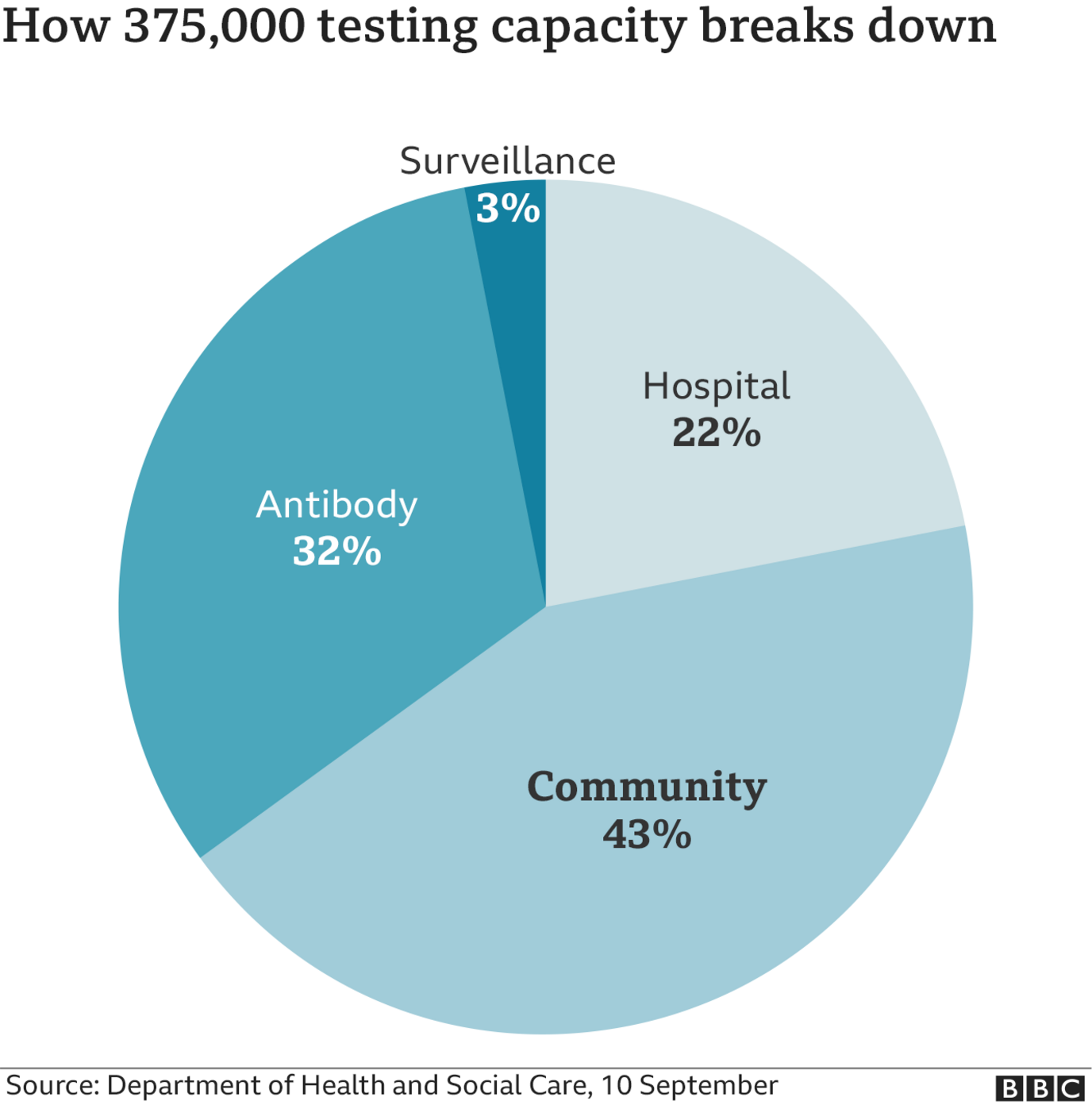

But this covers a number of different types of tests.

There are four "pillars" to the testing programme. The first is hospital testing, which is processed in hospital and university labs and reserved for patients and staff.

The second is the testing n the community - and is the element of the system that there is currently so much focus on.

The other two are an antibody testing programme, which looks at whether people have had the virus previously, and a surveillance programme run by the Office for National Statistics. This is considered to be an essential way of keeping track of the spread of the virus.

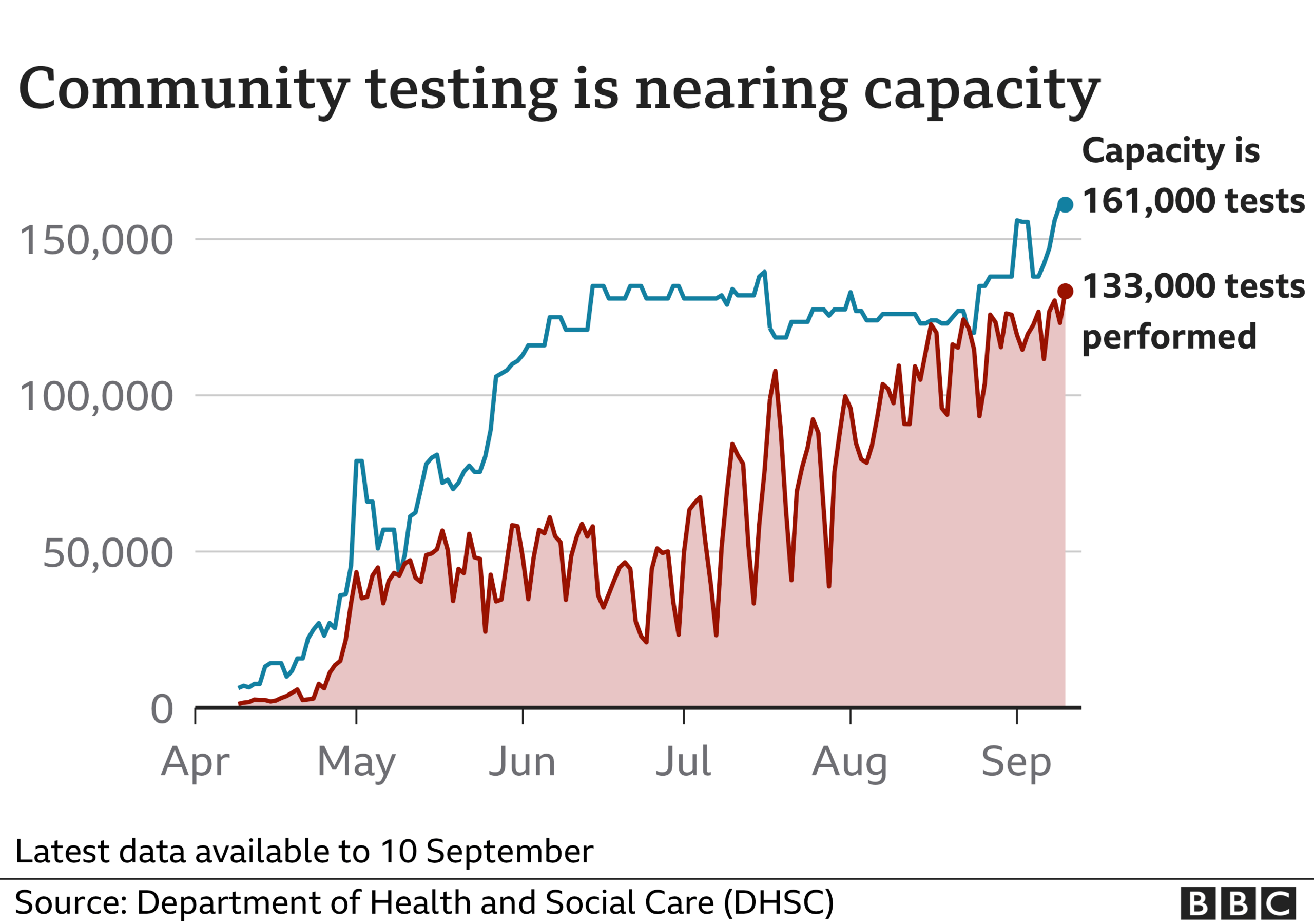

But the community labs are maxed out

Community testing capacity represents less than half the total.

And once we dig down more into this data, it becomes clear why tests have had to be rationed.

Nearly all the community testing is processed at one of five mega-labs. Back in August it was clear they were close to capacity - in fact all the testing capacity was used up on 23 August.

And this goes to the heart of the problem.

These labs were built in super-quick time. Ministers often refer to it as the biggest diagnostic testing expansion in history. That is because the UK had very few diagnostic testing facilities of this type. So it chose to centralise the system at these large labs and has worked with a variety of partners, including private companies and universities, to run them.

What's going on in the labs?

Prof Gordon Dougan, from the University of Cambridge, says it is not surprising they have run into problems and struggled to increase capacity to keep pace with demand. Despite "valiant efforts, the system is not robust enough" and is vulnerable to failure at multiple levels from sourcing equipment to finding the right staff, he says.

It is understood that one of the biggest limitations is hiring enough qualified people to carry out the tests.

YOUR QUESTIONS: We answer your queries

THE R NUMBER: What it means and why it matters

LOCAL LOCKDOWNS: What happens if you have one?

TEST AND TRACE: How does it work?

FURLOUGH: What happens when the scheme ends?

This has become a particular issue as academics and post-graduate students have returned to their usual roles. Labs have been unable to offer academic staff contracts. More experienced staff have had to go back to their institutions.

This has led to Prime Minister Boris Johnson writing letters to universities asking them to lend their staff and students for a little longer. It's not clear how many, if any, have agreed to this.

In order to process more tests, labs will need more space, machines and people. This is happening, but it seems not fast enough to keep up with demand.

What next?

Lab capacity is being increased. A sixth mega-lab in Newport is in the process of opening. A seventh near Loughborough will follow suit in the coming weeks.

This should have a big impact on capacity. But meanwhile, the government has said it will have to prioritise - that means making sure hospitals, care homes and areas with outbreaks can get access to testing.

Even when these new labs are fully up and running, there are concerns demand will still outstrip supply. Cases of coronavirus and other respiratory illnesses are going up, so it seems inevitable more people will be seeking access to tests.

An analysis by Health Data Research UK warned that if just 80% of people with annual coughs and fevers applied for a test, capacity could be exceeded for the whole winter.

Problems getting hold of tests could be a persistent problem in coming months.

Have you been affected by testing problems? Share your experiences by emailing haveyoursay@bbc.co.uk, external.

Please include a contact number if you are willing to speak to a BBC journalist. You can also get in touch in the following ways:

WhatsApp: +44 7756 165803

Tweet: @BBC_HaveYourSay, external

Please read our terms & conditions and privacy policy

If you are reading this page and can't see the form you will need to visit the mobile version of the BBC website to submit your question or comment or you can email us at HaveYourSay@bbc.co.uk, external. Please include your name, age and location with any submission.