Covid: The second wave is here - but how bad will it be?

- Published

The warning by the prime minister and his senior officials at Wednesday's televised briefing was stark.

Things, they said, are heading in the "wrong direction", leaving the UK at a "critical moment". Infections are on the rise and so too are hospital admissions and deaths.

There can be no doubt the second wave is now well and truly here. What remains to be seen is just how bad it will be.

UK not on doomsday trajectory

Last week chief scientific adviser Sir Patrick Vallance floated the idea that the UK could face 50,000 cases a day by mid-October if the rises seen in late August and September carried on.

It was based on cases doubling every seven days. But it is already clear we are not on that trajectory, although the picture is somewhat muddied by the continued problems people have accessing testing.

But the idea that we may be seeing relatively slow growth is re-enforced by the results of the latest React study, which is part of the government's wider surveillance programme. These suggest the R number - a measure of how fast infections are spreading - may have actually fallen.

However, what is providing most concern is the local peaks in the north-west and north-east of England, where there are much higher rates of infection.

Liverpool, Manchester and Newcastle have close to 10 times the level of infection than average.

It was a point picked up by chief medical adviser Prof Chris Whitty, who pointed out that other countries such as Italy had seen more localised outbreaks in the first wave, while the UK saw outbreaks seeded in nearly all parts of the country.

This, he said, raised the prospect of the second wave being more "highly concentrated" in fewer areas.

But cases are still rising everywhere - and, as always, things can change quickly.

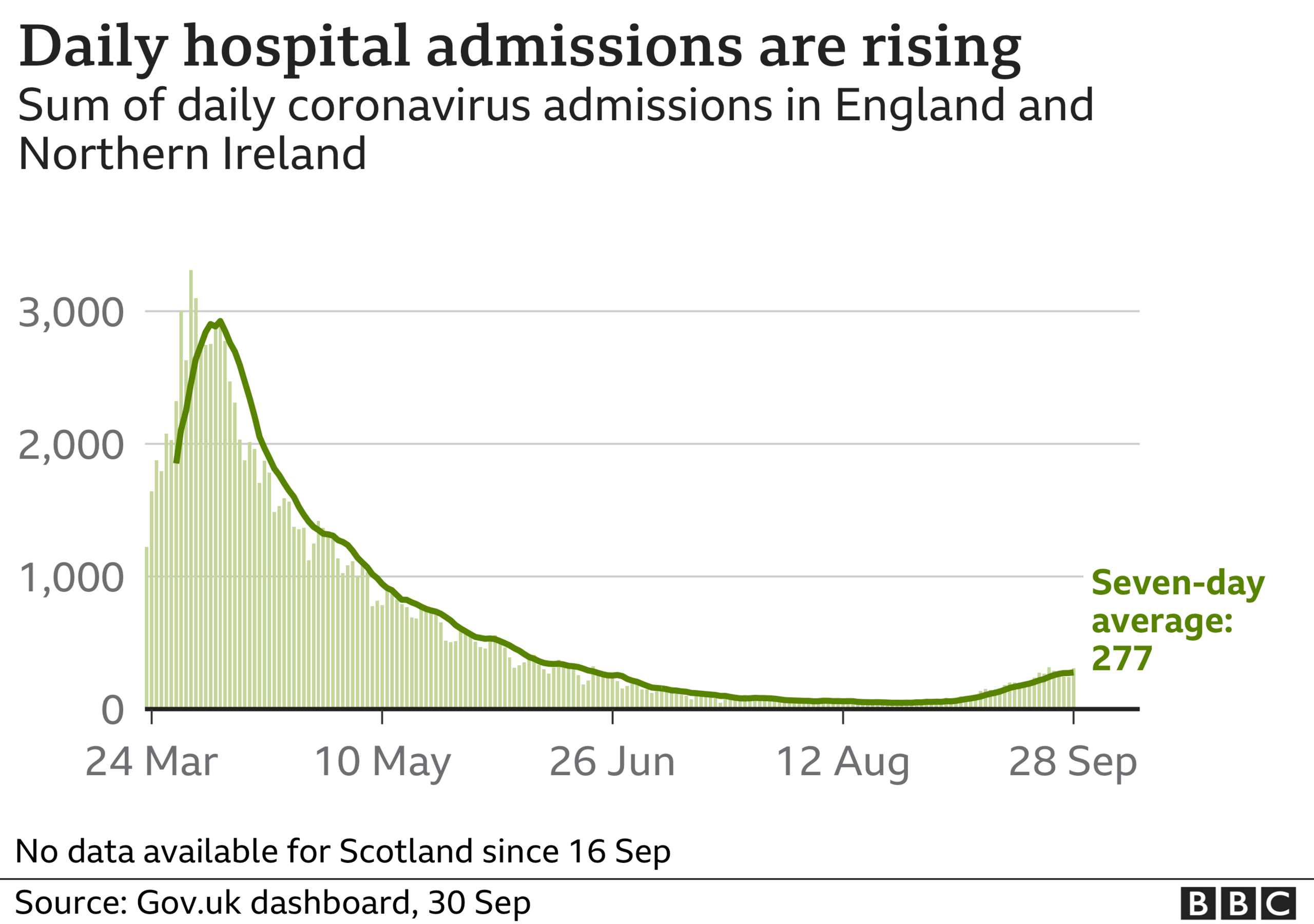

Hospital cases rising more slowly

Given the problems with testing, hospital admissions are arguably a much better metric than cases.

What is more, they are a measure of people who become seriously ill. Most people only have mild symptoms.

The trajectory is certainly upwards, but not sharply, and the numbers are nowhere near where they were at the peak.

In fact, the past few days show the numbers of people being admitted to hospital have dropped in England and Northern Ireland. (The way data is collected in Scotland and Wales means including their recent data is problematic.)

That is not to say they won't continue rising.

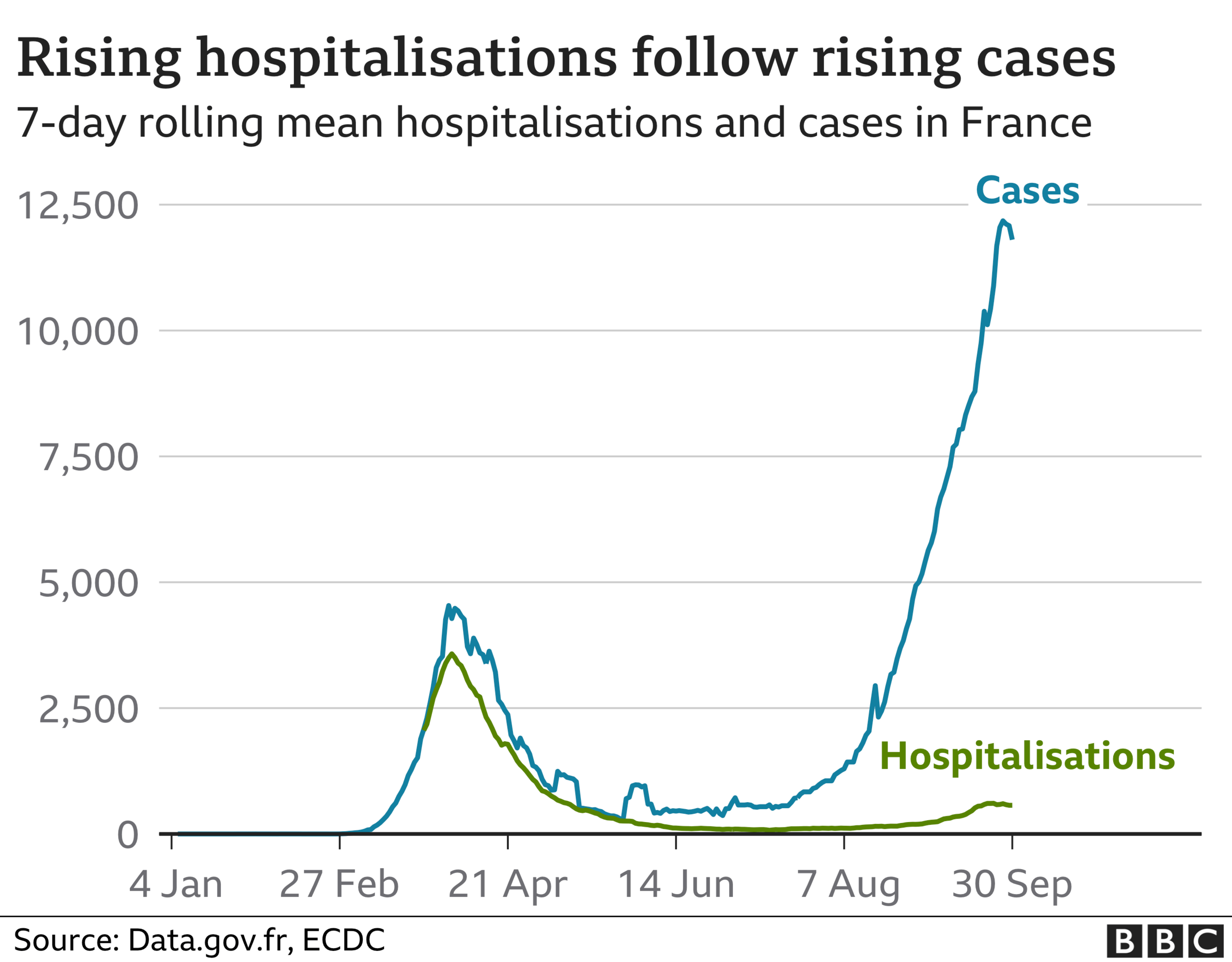

The experience of France, where cases started increasing earlier than in the UK, gives us some idea of what to expect: a gradual upward trend.

Prof James Naismith, director of Oxford University's Rosalind Franklin Institute, a medical research unit, says hospitalisations appear to be doubling every two weeks in the UK.

That, he says, will undoubtedly result in significantly more deaths and long-term illness in the coming months.

But again it is a long way from what was seen in the spring, when hospital cases doubled every five days at one point.

What does this mean for winter?

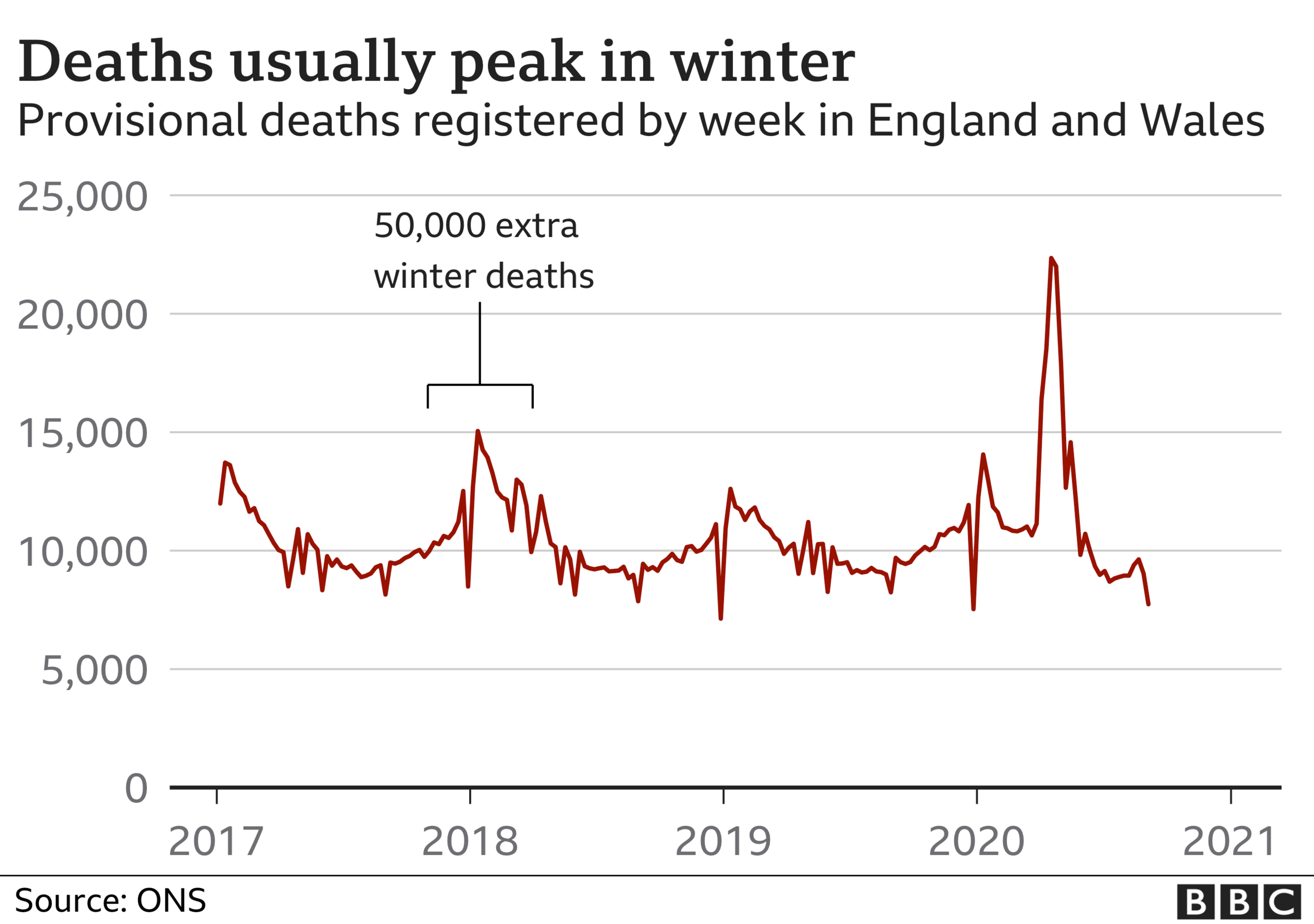

It seems unavoidable the numbers being brought into hospital will continue to climb.

This always happens for respiratory illnesses during this period. And the same, sadly, happens with deaths.

Some winters are, of course, worse than others.

December 2017 to March 2018 saw an extra 50,000 "winter deaths" in England and Wales - that is above what was being seen during the rest of the year. When you compare it with the winters before, there were 15,000 more deaths.

It was cold, there was a virulent strain of flu, and the vaccine that year was not particularly effective.

Given there is a new virus circulating that has a disproportionate effect on the most frail in society, most expect this winter to be worse than that.

Sir Mark Walport, a former chief scientific adviser to the government, believes crucial to what happens next will be "our behaviour" and how we all adhere to the rules on social distancing and self-isolation.

But there are other factors which mean the UK is in a stronger position than earlier in the year, so the deadly toll seen in the spring can and should be avoided.

A combination of better treatments for the seriously ill, the social-distancing measures introduced across society, and the fact the UK is better prepared to protect the most vulnerable.

There is more testing and PPE available for care homes, while vulnerable groups in the community will be taking more precautions than they were when the UK walked blind into the first wave. It is now pretty clear the virus was spreading widely before the alarm was raised in March.

The odds are certainly stacked in our favour more than they were six months ago.

This is - as Dr Simon Clarke, an infectious disease expert at the University of Reading, says - a "small silver lining".

But none of it should detract from the fact that it is only going to get more difficult from here on in.

Follow Nick on Twitter, external

- Published28 July 2020