Covid: How busy are hospitals as the second wave rolls in?

- Published

- comments

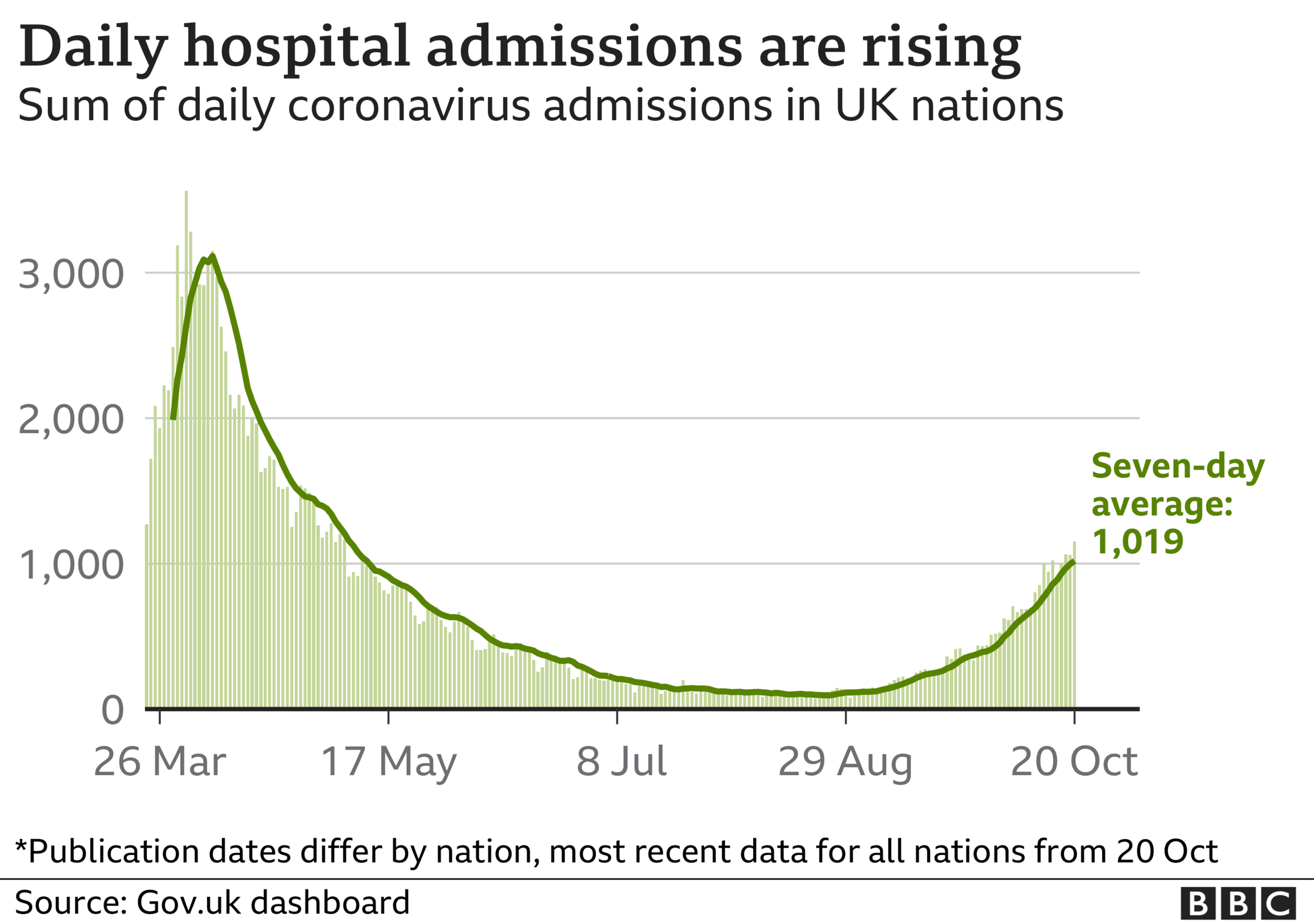

The second wave is placing an ever greater toll on UK hospitals. There are more than 1,000 Covid admissions a day - 10 times the rate at the end of summer.

Hospitals have started cancelling routine treatments, as happened during the first peak, with hospitals in Leeds this week following others in announcing some treatments will have to stop.

But just how busy is the NHS? And how much Covid can it take?

Cases still well below the peak

Admissions are up, but still nowhere near the numbers seen in the spring. At one point, more than 3,000 patients a day were being admitted.

Instead, we have seen a gradual rise - the numbers doubling every two weeks or so, compared with every four days at one stage of the first wave.

But consider what happens in more normal times. Winter typically sees more than 1,000 people a day admitted to hospital for respiratory problems.

Yet, this time, what we do not know is how much other viruses - flu, in particular - will add to the workload. An encouraging sign from the southern hemisphere earlier this year was that the flu season was very mild.

There are big regional differences

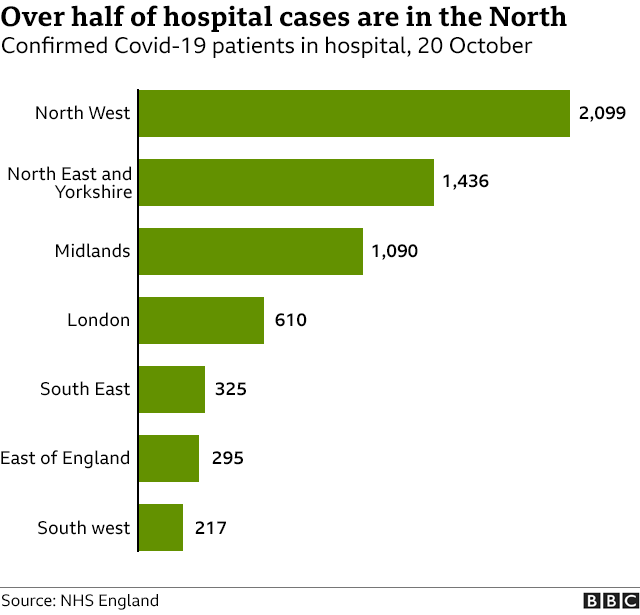

Despite the rising number of admissions, only about one in 15 UK hospital beds are occupied by a Covid patient. This national picture masks what is happening at a more local level. Hospitals in hotspot areas are much busier.

Look at the distribution of cases across the English regions.

Hospitals in the North West are currently caring for a third of England's Covid patients. Indeed, at some hospitals in the region, one in four beds is being used by someone fighting the virus.

That is taking its toll.

The number of Covid patients in Liverpool's hospitals has already exceeded that seen during the peak, says Dianne Brown, chief nurse at Liverpool University Hospitals. This, she says, has been "mentally, physically and emotionally exhausting" for staff.

The NHS is trying to do more

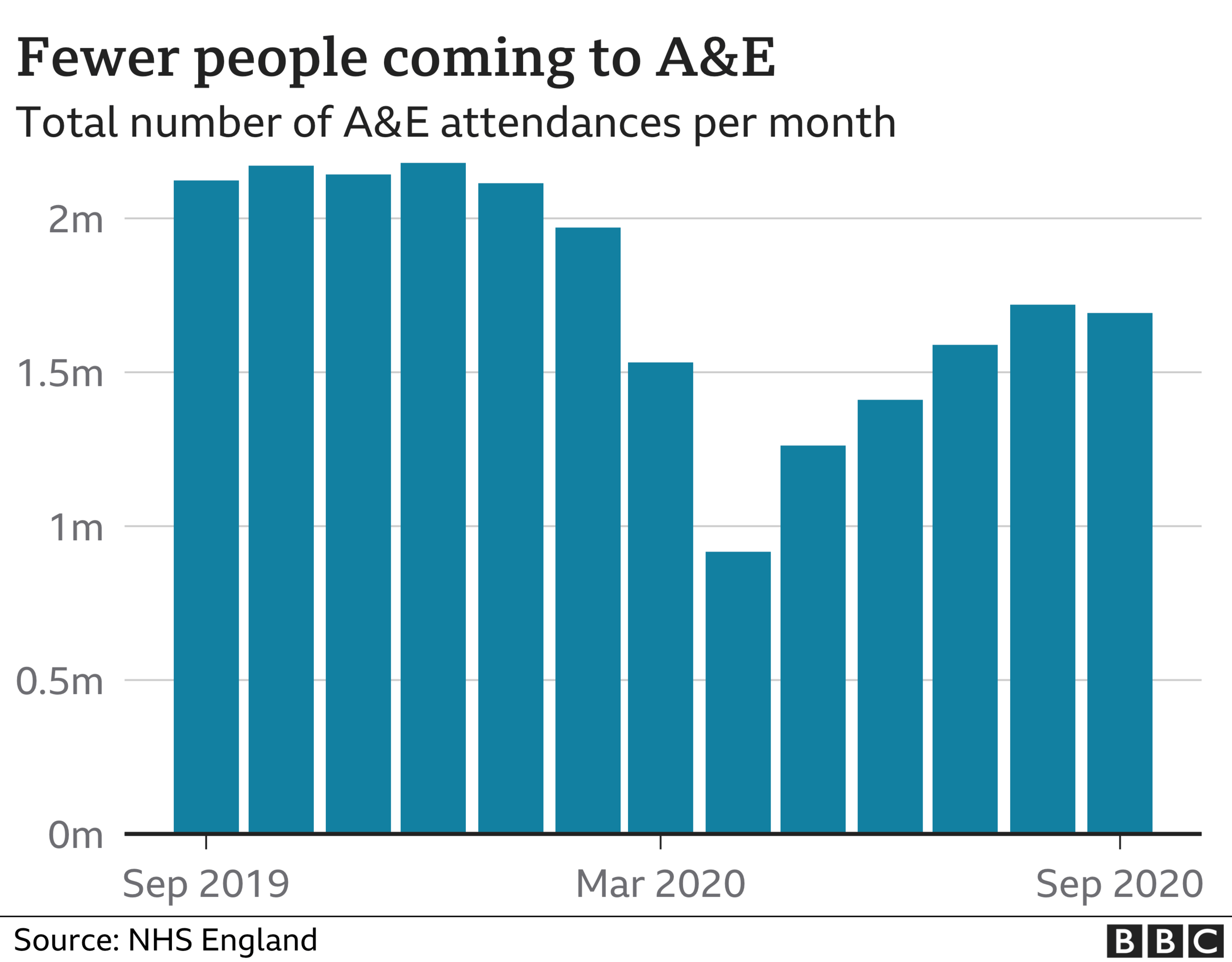

One crucial difference between then and now is that more non-Covid work is being done. Numbers of routine operations, A&E attendances and cancer treatments dropped significantly during the first wave, but have started climbing since.

This, of course, is a difficult balancing act. And for some trusts - local healthcare groups - it is proving a step too far. In the past week alone hospital bosses in Nottingham, Birmingham and Bradford have announced some of the routine work they are doing will have to be cut back before the Leeds announcement on Tuesday.

Nottingham University Hospitals chief executive Tracy Taylor says she had to act after a "dramatic increase" in cases effectively meant she was losing an extra ward every day to new Covid admissions.

But hospitals are probably far from full

What we can't say - because up-to-date figures are not being published by NHS bosses - is exactly how full hospitals actually are. In recent years, hospitals tend to have had about 90% of beds occupied at any one time.

In the summer, when the last audit was done, this had dropped to below 70% - there were few Covid cases and levels of non-Covid work were still below normal. Even taking into account the rise in Covid admissions, it probably leaves hospitals with thousands more beds than normal at this time last year.

But Chris Hopson, of NHS Providers, which represents health managers, says this distorts the "very difficult" job hospitals have in managing social distancing, PPE requirements and the need to segregate Covid and non-Covid patients.

"Hospitals effectively have between 10% and 30% less capacity than they would normally. You cannot expect every bed to be full."

One of the problems, he says, is that the NHS has so little wriggle room, having less space, equipment and beds than hospitals in other western European countries.

England's NHS medical director Prof Stephen Powis says there are measures in place to combat this with a "landmark deal" in place with the independent sector to carry out routine treatments and the network of field hospitals, known as Nightingales in England, available if needed.

In fact, the one in Manchester is expected to start taking non-Covid patients in the coming weeks to ease the pressure in the north west.

How much Covid can the NHS take?

The crucial question.

The aim of protecting the NHS was one of the main reasons for the national lockdown in the spring. As always there is a big focus on critical care capacity. The UK has close to 5,000 intensive care beds, but increased this by three-quarters in the first wave by converting operating theatres and recovery rooms into temporary facilities.

The NHS never got anywhere near needing all of them.

Critical care capacity has shrunk back to the normal levels and, even in the hardest hit regions, "surge capacity" has not been dipped into on any sort of scale.

But Nicki Credland, who chairs the British Association of Critical Care Nurses, says it would be wrong to assume this means the NHS is in the clear.

Increasingly patients are being treated with oxygen therapy on the wards, she says, rather than relying on mechanical ventilators as was done in the first wave.

"This can be done… for most patients, but it still needs highly trained staff."

And that, she says, is the crux of the problem.

"We may have the beds, we have the equipment and we may have all the space in the Nightingales - but we have a finite amount of staff. It won't take much this winter for things to reach crisis point."

Follow Nick on Twitter, external

THREE TIERS: How will the system work?

SOCIAL DISTANCING: Can I give my friends a hug?

LOOK-UP TOOL: How many cases in your area?

- Published28 July 2020