Covid-19: Oxford University vaccine is highly effective

- Published

The Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine is currently in the final stages of testing

The coronavirus vaccine developed by the University of Oxford is highly effective at stopping people developing Covid-19 symptoms, a large trial shows.

Interim data suggests 70% protection, but the researchers say the figure may be as high as 90% by tweaking the dose.

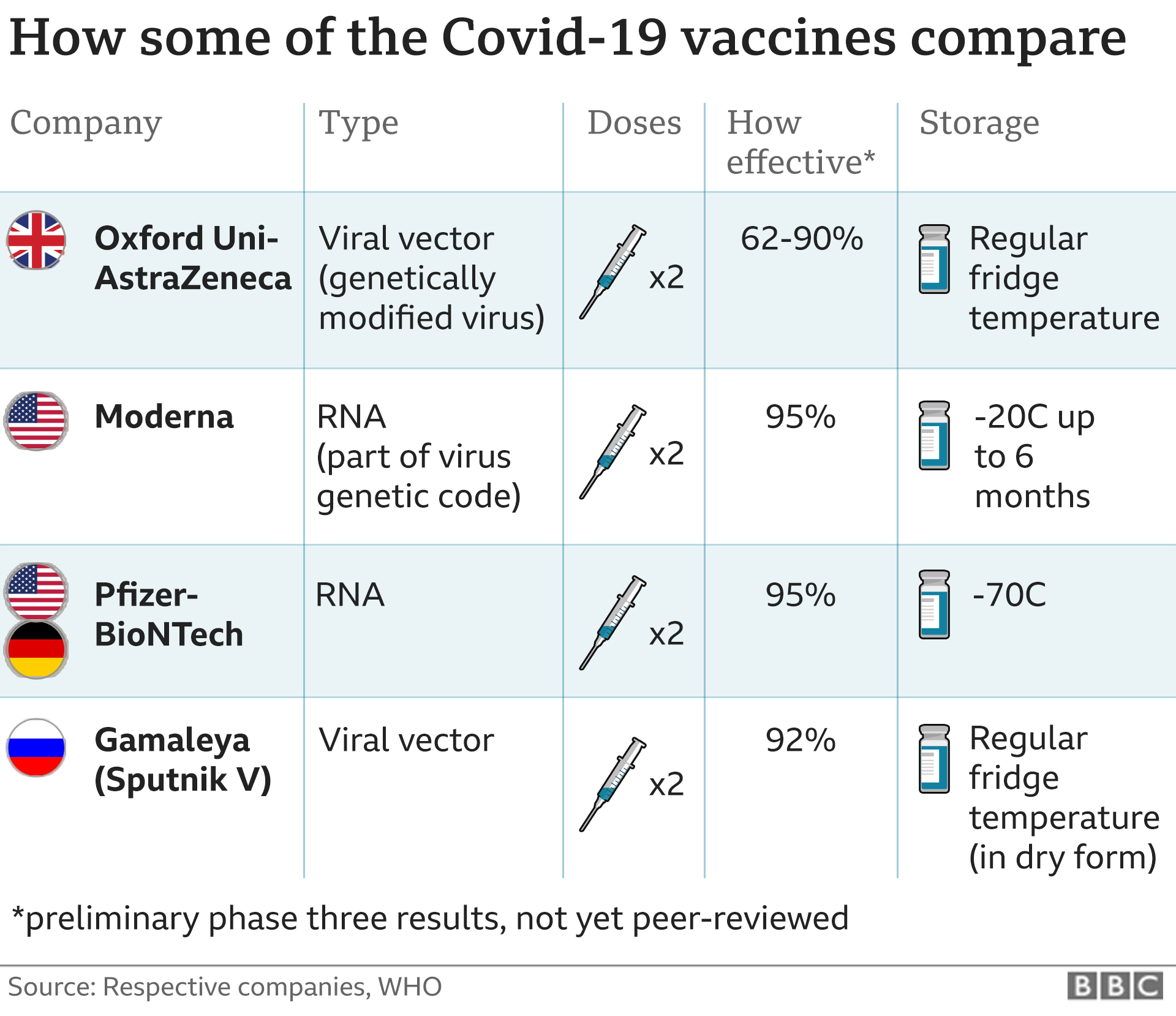

The results will be seen as a triumph, but come after Pfizer and Moderna vaccines showed 95% protection.

However, the Oxford jab is far cheaper, and is easier to store and get to every corner of the world than the other two.

So the vaccine will play a significant role in tackling the pandemic, if it is approved for use by regulators.

"The announcement today takes us another step closer to the time when we can use vaccines to bring an end to the devastation caused by [the virus]," said the vaccine's architect, Prof Sarah Gilbert.

The UK government has pre-ordered 100 million doses of the Oxford vaccine, and AstraZeneca says it will make three billion doses for the world next year.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson said it was "incredibly exciting news" and that while there were still safety checks to come, "these are fantastic results".

Speaking at a Downing Street briefing on Monday evening, Mr Johnson added that the majority of people most in need of a vaccination in the UK might be able to get one by Easter.

And Prof Andrew Pollard - director of the Oxford vaccine group - said it had been "a very exciting day" and paid tribute to the 20,000 volunteers in the trials around the world, including more than 10,000 in the UK.

AstraZeneca's Mene Pangalos says Covid vaccine is 'clearly effective'

What did the trial show?

The vaccine has been developed in around 10 months, a process that normally takes a decade.

There are two results from the trial of more than 20,000 volunteers in the UK and Brazil.

Overall, there were 30 cases of Covid in people who had two doses of the vaccine and 101 cases in people who received a dummy injection. The researchers said it worked out at 70% protection, which is better than the seasonal flu jab.

Nobody getting the actual vaccine developed severe-Covid or needed hospital treatment.

Prof Andrew Pollard, the trial's lead investigator, said he was "really pleased" with the results as "it means we have a vaccine for the world".

However, protection was 90% in an analysis of around 3,000 people on the trial who were given a half-sized first dose and a full-sized second dose.

Prof Pollard said the finding was "intriguing" and would mean "we would have a lot more doses to distribute."

The analysis also suggested there was a reduction in the number of people being infected without developing symptoms, who are still thought to be able to spread the virus.

Laura Foster explains why the Oxford vaccine matters

When will I get a vaccine?

In the UK there are four million doses of the Oxford vaccine ready to go. But nothing can happen until the vaccine has been approved by regulators who will assess the vaccine's safety, effectiveness, and that it is manufactured to high standard. This process will happen in the coming weeks.

It is also unclear who will get this vaccine or the other vaccines the government has ordered.

However, the UK is preparing to press the go button on an unprecedented mass immunisation campaign that dwarfs either the annual flu or childhood vaccination programmes.

Care home residents and staff will be first in the queue, followed by healthcare workers and the over-80s. The plan is to then to work down through the age groups.

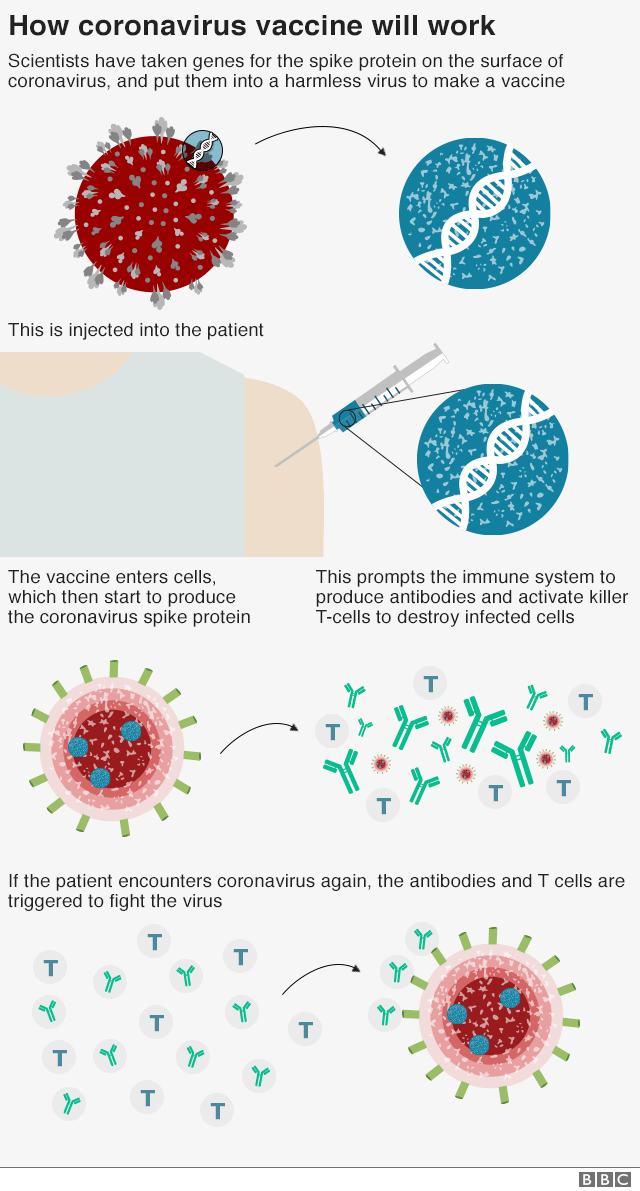

How does it work?

It uses a completely different approach to the vaccines from Pfizer and Moderna, which inject part of the virus's genetic code into patients.

The Oxford vaccine is a genetically modified common cold virus that used to infect chimpanzees.

It has been altered to stop it causing an infection in people and to carry the blueprints for part of the coronavirus, known as the spike protein.

Once these blueprints are inside the body they start producing the coronavirus' spike protein, which the immune system recognizes as a threat and tries to squash it.

When the immune system comes into contact with the virus for real, it will know what to do.

Why is the low dose better?

There is not a straightforward answer.

One idea is the immune system rejects the vaccine, which is built around a common cold virus, if it is given in too big an initial dose.

Or a low then high shot may be a better mimic of a coronavirus infection and lead to a better immune response.

Are the results disappointing?

After Pfizer and Moderna both produced vaccines delivering 95% protection from Covid-19, a figure of 70% is still highly effective, but will be seen by some as relatively disappointing.

But this is still a vaccine that can save lives from Covid-19 and is more effective than a seasonal flu jab.

It also has crucial advantages that make it easier to use. It can be stored at fridge temperature, which means it can be distributed to every corner of the world, unlike the Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna vaccines, which need to be stored at much colder temperatures.

The Oxford vaccine, at a price of around £3, also costs far less than Pfizer's (around £15) or Moderna's (£25) vaccines.

And the Oxford technology is more established, so the vaccine is easier to mass produce cheaply. AstraZeneca has also made a "no-profit pledge".

Elisa Granato was one of the volunteers given the Oxford vaccine

What difference will this make to my life?

A vaccine is what we've spent the year waiting for and what lockdowns have bought time for.

However, producing enough vaccine and then immunising tens of millions of people in the UK, and billions around the world, is still a gargantuan challenge.

Life will not return to normal tomorrow, but the situation could improve dramatically as those most at risk are protected.

Health Secretary Matt Hancock told BBC Breakfast we would be "something closer to normal" by the summer but "until we can get that vaccine rolled out, we all need to look after each other".

What's the reaction been?

Prof Peter Horby, from the University of Oxford but not involved in the trial, said: "This is very welcome news, we can clearly see the end of tunnel now. There were no Covid hospitalisations or deaths in people who got the Oxford vaccine."

Dr Stephen Griffin, from the University of Leeds, said: "This is yet more excellent news and should be considered tremendously exciting. It has great potential to be delivered across the globe, achieving huge public health benefits.

England's chief medical officer, Prof Chris Whitty, expressed an "absolutely massive thank you" to people up and down the country who are volunteering for studies into Covid-19.

"Because as we've repeatedly said, it's only science that is going to get us out of this hole," he said, adding that "it will be a long haul".

Follow James on Twitter, external"

What questions do you have about the Oxford University vaccine?

In some cases your question will be published, displaying your name, age and location as you provide it, unless you state otherwise. Your contact details will never be published. Please ensure you have read our terms & conditions and privacy policy.

Use this form to ask your question:

If you are reading this page and can't see the form you will need to visit the mobile version of the BBC website to submit your question or send them via email to YourQuestions@bbc.co.uk, external. Please include your name, age and location with any question you send in.

THE GLOBAL RACE TO FIND A VACCINE: How to Vaccinate the World