Oxford vaccine: How did they make it so quickly?

- Published

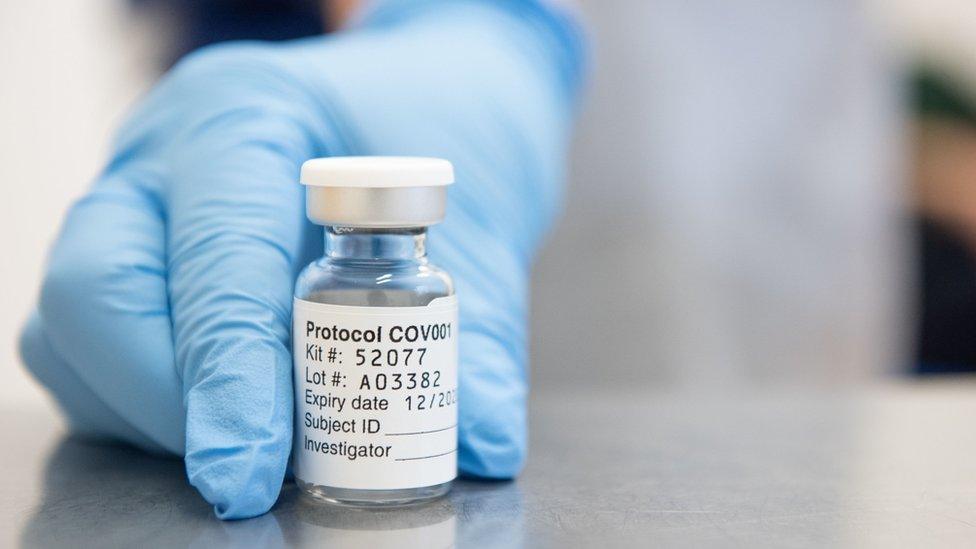

Trials of the vaccine have been carried out around the world

Ten years' vaccine work achieved in about 10 months. Yet no corners cut in designing, testing and manufacturing.

They are two statements that sound like a contradiction, and have led some to ask how we can be sure the Oxford vaccine - which has published its first results showing it is highly effective at stopping Covid-19 - is safe when it has been made so fast.

So, this is the real story of how the Oxford vaccine happened so quickly.

It is one that relies on good fortune as well as scientific brilliance; has origins in both a deadly Ebola outbreak and a chimpanzee's runny nose; and sees the researchers go from having no money in the bank to chartering private planes.

The work started years ago

We were planning how can we go really quickly to have a vaccine in someone in the shortest possible time

The biggest misconception is the work on the vaccine started when the pandemic began.

The world's biggest Ebola outbreak in 2014-2016 was a catastrophe. The response was too slow and 11,000 people died.

"The world should have done better," Prof Sarah Gilbert, the architect of the Oxford vaccine, told me.

In the recriminations that followed, a plan emerged for how to tackle the next big one. At the end of a list of known threats was "Disease X" - the sinister name of a new, unknown infection that would take the world by surprise.

The Jenner Institute at the University of Oxford - named after the scientist that performed the first vaccination in 1796, and now home to some of the world's leading experts - designed a strategy for defeating an unknown enemy.

"We were planning how can we go really quickly to have a vaccine in someone in the shortest possible time," Prof Gilbert said.

"We hadn't got the plan finished, but we did do pretty well."

The critical piece of technology

The central piece of their plan was a revolutionary style of vaccine known as "plug and play". It has two highly desirable traits for facing the unknown - it is both fast and flexible.

Conventional vaccines - including the whole of the childhood immunisation programme - use a killed or weakened form of the original infection, or inject fragments of it into the body. But these are slow to develop.

Instead the Oxford researchers constructed ChAdOx1 - or Chimpanzee Adenovirus Oxford One.

Scientists took a common cold virus that infected chimpanzees and engineered it to become the building block of a vaccine against almost anything.

Before Covid, 330 people had been given ChAdOx1 based-vaccines for diseases ranging from flu to Zika virus, and prostate cancer to the tropical disease chikungunya.

The virus from chimps is genetically modified so it cannot cause an infection in people. It can then be modified again to contain the genetic blueprints for whatever you want to train the immune system to attack. This target is known is an antigen.

ChAdOx1 is in essence a sophisticated, microscopic postman. All the scientists have to do is change the package.

"We drop it in and off we go," said Prof Gilbert.

January 1

We'd been planning for disease X, we'd been waiting for disease X, and I thought this could be it.

While much of the world was having a lie-in after New Year's Eve, Prof Gilbert noticed concerning reports of "viral pneumonia" in Wuhan, China. Within two weeks scientists had identified the virus responsible and began to suspect it was able to spread between people.

"We'd been planning for disease X, we'd been waiting for disease X, and I thought this could be it," Prof Gilbert said.

At this point, the team did not know how important their work would become. It started out as a test of how fast they could go and as a demonstration of the ChAdOx1 technology.

Prof Gilbert said: "I thought it might only have been a project, we'd make the vaccine and the virus would fizzle out. But it didn't."

A lucky break

It sounds strange to say it, almost perverse, but it was lucky that the pandemic was caused by a coronavirus.

This family of viruses had tried to jump from animals to people twice before in the past 20 years - Sars coronavirus in 2002 and Mers coronavirus in 2012.

It meant scientists knew the virus's biology, how it behaved and its Achilles heel - the "spike protein".

"We had a huge head start," Prof Andrew Pollard from the Oxford team said.

The spike protein is the key the virus uses to unlock the doorway into our body's cells. If a vaccine could train the immune system to attack the spike, then the team knew they were odds-on to succeed.

And they had already developed a ChAdOx1 vaccine for Mers, external, which could train the immune system to spot the spike. The Oxford team were not starting from scratch.

"If this had been a completely unknown virus, then we'd have been in a very different position," Prof Pollard added.

It was also lucky that coronaviruses cause short-term infections. It means the body is capable of beating the virus and a vaccine just needs to tap into that natural process.

If it had been a long-term or chronic infection that the body cannot beat - like HIV - then it's unlikely a vaccine could work.

On 11 January, Chinese scientists published and shared with the world the full genetic code of the coronavirus.

The team now had everything they needed to make a Covid-19 vaccine.

All they had to do was slip the genetic instructions for the spike protein into ChAdOx1 and they were good to go.

Money, money, money

The first bit was quite painful. There was a period when we didn't have any money in the bank.

Making a vaccine is very expensive.

"The first bit was quite painful. There was a period when we didn't have any money in the bank," said Prof Pollard.

They had some funding from the university, but they had a crucial advantage over other groups around the world.

On the site of Churchill hospital in Oxford is the group's own vaccine manufacturing plant.

"We could say stop everything else and make this vaccine," said Prof Pollard.

It was enough to get going, but not to make the thousands of doses needed for larger trials.

"Getting money was my main activity until April, just trying to persuade people to fund it now," said Prof Gilbert.

But as the pandemic tightened its grip on the world and country after country descended into lockdown, the money started to flow. Production of the vaccine moved to a facility in Italy and the money helped solve problems that would have otherwise held up the trials, including the logistical nightmare of lockdown Europe.

"At one point we had to charter a plane, the vaccine was in Italy and we had clinics here the next morning," said Prof Gilbert.

Unglamorous, but vital checks

Quality control is never the sexiest part of a project, but researchers cannot start giving an experimental vaccine to people until they are sure it has been made to a high enough standard.

At every stage of the manufacturing process, they needed to ensure the vaccine was not being contaminated with viruses or bacteria. In the past this had been a lengthy process.

"If we had not been thinking about how to shorten the time, we might have had a vaccine in March but not started trials until June."

Instead, once animal trials had shown the vaccine was safe, the researchers were able to begin human trials of the vaccine on 23 April.

Back-to-back trials

Since then the Oxford vaccine has been through every stage of trials that would normally take place for a vaccine.

There is a pattern to clinical trials:

Phase one - the vaccine is tested in a small number of people to check it is safe

Phase two - safety tests in more people, and to look for signs the vaccine is producing the required response

Phase three - the big trial, involving thousands of people, to prove it actually protects people

The Oxford vaccine has been through each of those stages, including 30,000 volunteers in the phase three trial, and the team has as much data as any other vaccine trial.

What hasn't happened is years of hanging around in between each phase.

The process is long, not because it needs to be and not because it's safe, but because of the real world.

Dr Mark Toshner, who has been involved in the trials at sites in Cambridge, said the idea that it took 10 years to trial a vaccine was misleading.

He told the BBC: "Most of the time, it's a lot of nothing."

He describes it as a process of writing grant applications, having them rejected, writing them again, getting approval to do the trial, negotiating with manufacturers, and trying to recruit enough people to take part. It can take years to get from one phase to the next.

"The process is long, not because it needs to be and not because it's safe, but because of the real world," Dr Toshner said.

Safety has not been sacrificed. Instead the unparalleled scientific push to make the trials happen, the droves of people willing to take part, and of course the money blew many of the usual hold-ups aside.

That does not mean problems will not appear in the future - medical research cannot make those guarantees. Usually, side-effects of vaccines appear either at the time they are given or a few months afterwards. It is possible that rarer problems could emerge when millions of people are immunised, but this is true of every vaccine that has ever been developed.

The next stage will be fast too

Plans for giving regulatory approval and manufacturing the vaccine have also been dramatically speeded up.

The UK already has four million doses of the vaccine ready to deploy. The Oxford team partnered with pharmaceutical giant AstraZeneca, and the manufacture of the vaccine started long before the results came in. At the time it was a gamble, but it has paid off big time.

Regulators, who would normally wait until after the trials were concluded, have also been involved early.

The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency in the UK has been conducting "rolling reviews" of the safety, manufacturing standards and effectiveness of the Oxford vaccine. It means a decision on whether the vaccine can be used will come early.

The Oxford vaccine has - like those of Pfizer and Moderna - arrived in record time to a world in desperate need.

Follow James on Twitter, external

- Published23 November 2020

- Published23 November 2020

- Published19 November 2020

- Published21 October 2020