Coronavirus: 'How long can we keep going like this? About a week'

- Published

WATCH: ICU hospital staff "scared, sad, petrified, worried"

I'm standing in what should be an operating theatre - but instead it's been converted into an intensive care unit for Covid-19 patients on ventilators.

This is the first time I have seen it full of patients like this. Normally this theatre would be busy with major cancer surgery, but that's been transferred to another building.

A children's recovery area, still decorated with colourful stickers of cartoons, is once again filled with desperately sick adults. Every day, more wards are being transformed into ICU - ready for the next influx of patients.

'Scared, sad, petrified, worried'

We have been given access to University College Hospital, in central London. This is the same intensive care unit that I first visited in April, during the first peak.

It is one of the busiest hospitals in the capital and intensive care here is expanding across a hospital that is under pressure like never before, from a relentless rise in Covid admissions.

I am struck by the toll the pandemic is taking on staff. It's immense - both physically and mentally. They are shell-shocked. "My emotions are all over the place. Scared, sad, petrified, worried," one ICU nurse tells me.

I asked one of the consultants who I've met several times in the last year, Dr Jim Down, how long they can keep going like this - and the answer was stark. "At this rate, about a week. After that we really need to see it slow down or we're going to see the care we can deliver suffering."

They have got three times as many critically ill patients in the hospital as normal. The number of Covid admissions to London hospitals has doubled in just two weeks - they're more stretched now than at the peak last April. Senior staff are worried.

Dr Alice Carter compares it to an elastic band that is close to snapping. "It gets to a point where you stretch so far it never returns back to its baseline. I think that's probably where we are now. It's not going to take much more for that elastic band to break, and that's the real fear for us at the moment."

Dr Alice Carter: 'It's not going to take much more for that elastic band to break'

That could have very serious consequences, she adds. "If we get to that point, we can't offer anyone ICU, not just Covid patients, but anyone who has a traffic accident or a heart attack or a stroke - whatever it is, to take them in."

For 38-year-old Rachel Arfin, one of the three pregnant women in intensive care with Covid-19, treatment is more complicated. Her baby is due in five weeks and the staff have to monitor them both.

"They can't do anything that will harm the baby," she says. "All the time [they are] checking, monitoring the baby." She is reassured by the "beautiful sound" of her baby's heartbeat.

"They are looking after two people in one. They're saving lives," says Rachel. But her children - she has seven - keep asking when she's coming home.

Rachel Arfin's baby is due in five weeks - both are doing well

I've reported from here several times during the pandemic and am always struck by the professionalism and dedication of staff. It's always quiet and calm, but that belies what's actually happening. This is a system under strain like never before.

The warning signs are clear, the NHS is on the brink. Unless infection rates fall, soon it will have a serious impact. The pressure on staff is unrelenting. I saw two nurses in tears.

Compared to when I visited in April, it's a lot busier. In some ways, it's more structured - they now know what they're dealing with. They've got new treatments, such as the drug dexamethasone, which they didn't have last time. And many of the staff have now had the first dose of the vaccine.

But other aspects don't get any easier, such as the emotional burden of breaking bad news over a telephone or video call. It is very different to being able to hold someone's hand.

Staff say they don't know which patients to help first

ICU staff have incredibly high standards. They're used to doing everything meticulously and perfectly. And they're doing all they can. But sometimes they go home and feel guilty that they can't do more. The impact on nurses - the bedrock of care in intensive care - is visible.

The highly specialised staff are usually one-to-one with patients. Deputy sister Ashleigh Shillingford is looking after three or four ventilated patients at a time, with one other junior member of staff. It's emotional and often devastating work.

"We are so stretched we have to prioritise and prioritising care is not the NHS that I grew up in - we shouldn't have to choose which patient gets what care first." She says she's never had to make decisions like these before.

"You just don't know who to help first. The patients are losing their lives at a dramatic speed, we're not just getting old people," she says, "these are young people that we're getting."

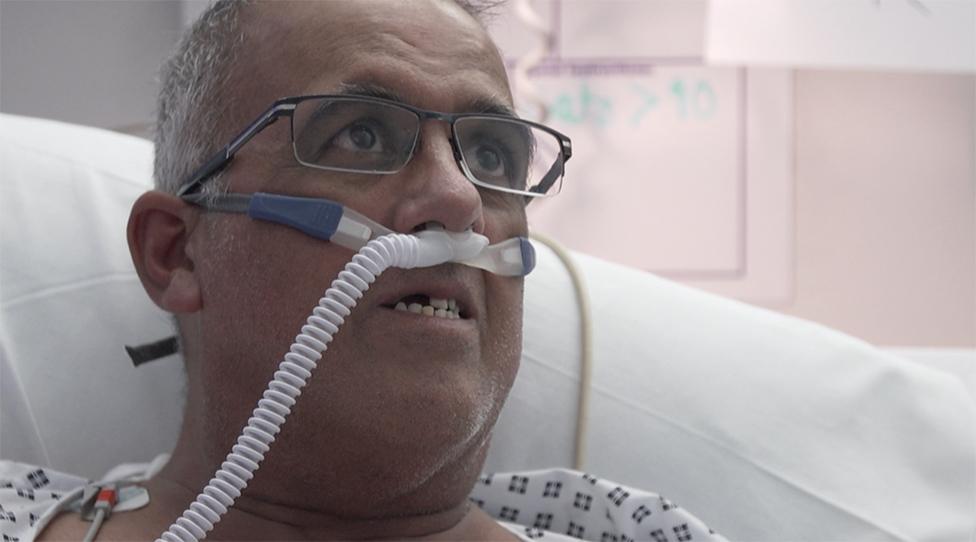

Gerald Williams, 58, is awaiting chemotherapy for lung cancer and had been shielding, but he still caught coronavirus. "All of a sudden, out of the blue, Covid came knocking on my door and it's frightening - you don't know how you're getting your next breath," he says.

Gerald Williams had been shielding but he still caught coronavirus

He wants to get home to his daughters, the youngest of whom is 13. And he's annoyed at those who don't take it seriously. "People are moaning and groaning. Even in A&E. They need to get a life. Don't be idiots, forget about meeting your mate, stay home. No-one is invulnerable."

For now the Trust is coping better than many others in London and is still taking Covid patients from other hospitals. But the next few weeks could be the biggest challenge the NHS has ever faced - and it will be its doctors and nurses who will bear the brunt for all of us.

Follow @BBCFergusWalsh, external on Twitter

As the BBC's medical editor, Fergus Walsh has been reporting on the Covid-19 pandemic and its immense impact on the UK.