Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine: Bogus reports, accidental finds - the story of the jab

- Published

Prof Teresa Lambe, who designed the vaccine over a weekend

In the early hours of Saturday 11 January, Prof Teresa Lambe was woken up by the ping of her email. The information she had been waiting for had just arrived in her inbox: the genetic code for a new coronavirus, shared worldwide by scientists in China.

She got to work straight away, still in her pyjamas, and was glued to her laptop for the next 48 hours. "My family didn't see me very much that weekend, but I think that set the tone for the rest of the year," she says.

By Monday morning, she had it: the template for a new experimental coronavirus vaccine. The first death from the new virus was reported around the same time, but it was still a month before the disease it causes was named Covid-19.

Lambe's team at Oxford University's Jenner Institute, led by Prof Sarah Gilbert, was always on the lookout for Disease X - the name given to the unknown infectious agent that could trigger the next pandemic. They had already used their experimental vaccine system against malaria and flu and, crucially, against another type of coronavirus, Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome (Mers). So they were confident it could work again.

That weekend was the first step on a journey to create a vaccine at lightning speed, for a disease that would, in a matter of months, claim more than 1.5 million lives. I have been following the efforts of the Oxford scientists since the start. There have been dramas along the way, including:

a rush to charter a jet when a flight-ban prevented vaccine from getting into the country

dismay at totally false reports on social media that the first volunteer to be immunised had died

concern that falling infection rates over the summer would jeopardise the hope of quick results

how an initial half-dose of the vaccine unexpectedly provided the best protection

an admission from the chief of Oxford's partner, drug company AstraZeneca, that it would have run the trials "a bit differently".

In the middle of January Prof Andrew Pollard, the director of the Oxford Vaccine Group, which runs clinical trials, shared a taxi with a modeller who worked for the UK government's Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies. During the journey, the scientist told him data suggested there was going to be a pandemic not unlike the 1918 flu.

"I went from someone who was aware of a small outbreak in China, which was of academic interest, to realising that it was going to change our lives. It was a chilling moment," Pollard says.

Prof Sarah Gilbert, the architect of the Oxford vaccine

Pollard got in touch with Gilbert and found her team at the Jenner Institute was already working on a vaccine. They agreed to collaborate on a clinical trial.

By February the virus had spread to more than two dozen countries, including the UK and the US. There had been more than 1,000 deaths in China.

But getting funding for trials was still a struggle. It was all Gilbert thought about, getting up at 04:00 to "write the grant application trying to persuade somebody that money I'd been awarded for a different project would actually be better spent on this project," she says.

The team behind the Oxford University vaccine discuss their work

It was another month before the UK was put into lockdown, and the government announced funding to support clinical trials and manufacturing. This meant the vaccine could go into production.

The first doses were made at the university's own bio-manufacturing facility after Prof Catherine Green had created a cell culture from which it could be grown, using Lambe's blueprint.

The science behind the vaccine is fascinating. It is created from a modified virus that causes the common cold in chimpanzees, which has had a tiny bit of genetic material removed so that it can't trigger infection in humans. Into this gap is inserted a fragment of the genetic code for coronavirus. This forms the vaccine. The technical term is a viral vector vaccine.

Such vaccines are grown in human cell culture which has a gene added to allow the viral particles to multiply at an enormous rate. Billions and billions are grown in bioreactors, and then purified. One of the team said it was like the recipe for Coke - once you knew the secret, and followed a formula, it could be done anywhere. Having seen the procedure, with all the technicians, working on different parts of the recipe, I prefer to think of it as a bit like a Vaccine MasterChef.

But lockdown brought significant challenges. Getting hold of PPE was a logistical nightmare, and Green was reduced to making hand sanitiser in the lab. Her team worked round the clock, doing double shifts, seven days a week.

"We didn't wait for the results of one stage before we went on to the next stage," she says. "So we took a risk... We still did the checks and if the checks had come back as a fail, we'd have had to throw away all the things we'd done."

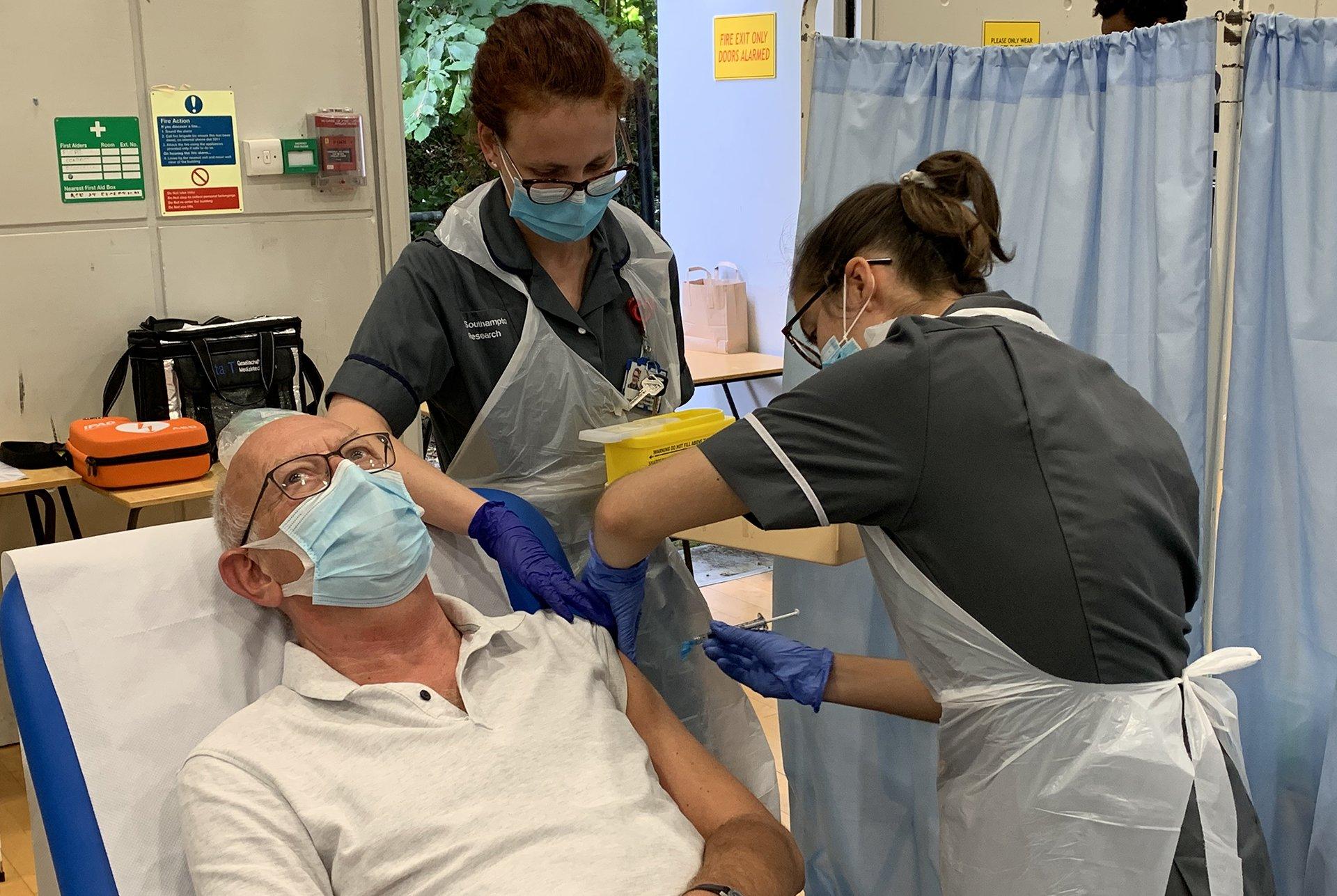

The checks did not fail, and after seven weeks they had enough doses of the vaccine to start the first trial. By this stage 10,000 volunteers had been recruited - all of them signing up within a matter of hours. Elisa Granato, a microbiologist, and Edward O'Neill, a cancer researcher, were the first two to receive Oxford's trial jab in April.

For Lambe, the vaccination of the first individuals was a monumental step. "I remember walking home from the lab and almost breaking down because we had a vaccine and got it into somebody's arm," she says.

The team waited 48 hours to check Granato and O'Neill had had no serious adverse reactions. With both doing well, they immunised a further six volunteers, and then gradually ramped up the numbers.

Elisa Granato was the first volunteer to be injected

But only a few days later there were shocking reports on social media that the first volunteer, Granato, had died.

It wasn't true. I spoke to her that day, and she told me she had never felt better. I posted a bit of the interview online, external. It helped quash the story, but not completely. Bizarrely, there were suggestions the interview might be fake and she really needed to hold up that day's newspaper to the camera as "proof of life".

"It was very upsetting," says Gilbert. "A lot of work had to be done, for her sake as well as for the trial's sake, to make it clear that this was just fake news."

Disinformation spreads fast and has the potential to undo months of hard work. Green found it very stressful. "Oh God it's awful! To think how malicious that can be, how people are really spreading nasty things… that doesn't feel fair because my team were all doing their best," she says.

As the trial grew, it was clear that Oxford's small manufacturing facility would not be able to keep up with demand. The team decided to outsource some of the manufacturing to Italy. But when the first batch was ready, there was a snag - the Europe-wide lockdown meant there were no flights to airlift it from Rome.

"Eventually we chartered a plane to bring 500 doses of vaccine because it was the only way we could get it here in time," says Green.

This is a really important part of the story which ended up being highly significant months later.

The Italian manufacturers used a different technique to Oxford to check the concentration of the vaccine - effectively how many viral particles are floating in each dose. When the Oxford scientists used their method, it appeared that the Italian vaccine was double strength. What to do? Calls were made to the medical regulators. It was agreed that volunteers should be given a half measure of the vaccine, on the basis that it was likely to equate to something more like a regular dose. This was partly a safety issue - they preferred to give them too little rather than too much.

But after a week, the scientists became aware that something unusual was going on. The volunteers were getting none of the usual side-effects - such as sore arms or fever. About 1,300 volunteers had only received a half-dose of the vaccine, rather than a full one. The independent regulators said the trial should continue and that the half-dose group could remain in the study.

The Oxford team bristle at any suggestion that there was a mistake, error, call it what you will. Perhaps the most accurate characterisation is that the volunteers were inadvertently given a lower dose. In months to come, they would be the stellar group in terms of vaccine efficacy.

From the start, the team at Oxford had had the goal of creating a vaccine that could help the world. To do that they would need billions of doses - something only industry could provide.

Sir Mene Pangalos, of the Cambridge-based pharmaceutical giant AstraZeneca, suggested the company could help.

But there was a potential hitch - Oxford insisted the vaccine should be affordable, which meant no profit for the pharmaceutical company. "Not usually the way big pharma works," says Pollard.

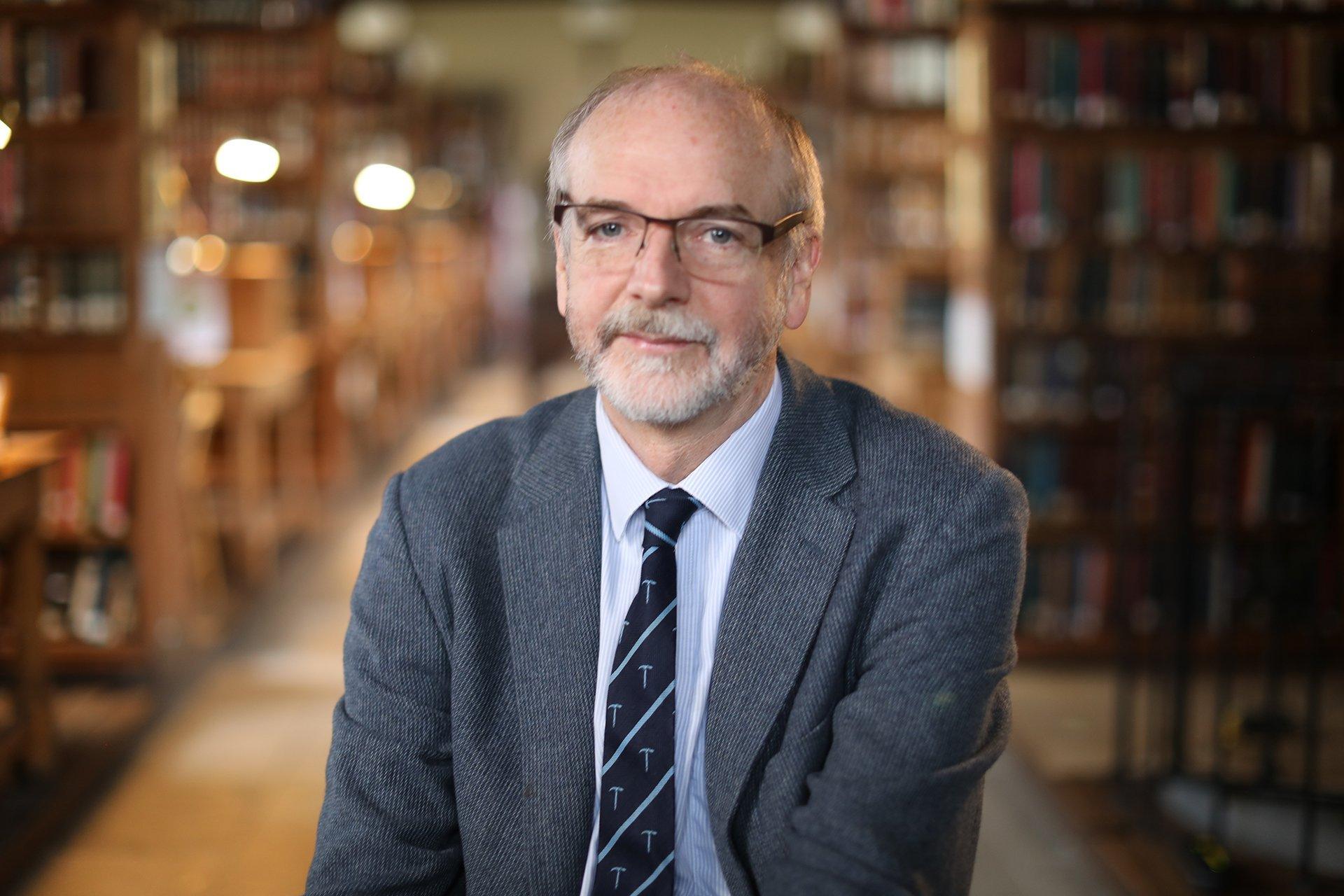

Prof Andrew Pollard

After intense negotiations, they reached a deal at the end of April. The vaccine would be provided on a not-for-profit basis worldwide, for the duration of the pandemic, and always at cost to low- and middle-income countries.

Most importantly of all, AstraZeneca agreed to take on the financial risk, even if the vaccine turned out not to work.

In May, in a huge vote of confidence, the UK government agreed to buy 100 million doses and provided nearly £90m in support.

By then there were nearly a dozen coronavirus vaccines in human trials around the world.

There's a mixture of anticipation, tinged with: Oh, I really hope it works!

At the start of summer, levels of coronavirus infection were falling in the UK. While this was good news for society, it made life more difficult for the trial, which relied on volunteers being exposed to coronavirus in order to figure out if the vaccine would protect them.

"There was a real risk that we wouldn't be able to get the answers that we'd hoped for really quickly," says Pollard.

They decided to expand to 19 sites around the UK.

For a vaccine that was intended for global use, it was important to test it in other countries too, to see how it worked in different populations. Trials began in South Africa and Brazil - which would soon have the second-highest death toll after the United States.

There is not one vaccine that can do the whole world, so the more the merrier

On 20 July, the initial results were released, showing whether the vaccine had stimulated the immune systems of the first 1,000 volunteers. The team was feeling the pressure.

"I've worked in vaccines for long enough to know that most vaccines actually don't work. And it's the worst feeling in the world to have such high expectations and then to see nothing," says Prof Katie Ewer, who leads the team studying T-cell response.

It was good news, though. The vaccine appeared to be safe, and had triggered the two-pronged immune response they were hoping for - producing antibodies which neutralise the virus, and T cells which can kill cells which have become infected. But the data also led to a change of strategy. Until then, the Oxford team had hoped to produce a vaccine that could be delivered in a single dose, so there was more vaccine to go round.

However, 10 participants who were given two doses showed a much stronger immune response, so all volunteers were invited back for a booster, to maximise the chances of protection.

Although these early results were promising, at this stage there was still no evidence to show whether the vaccine would actually protect against Covid-19.

What's more, up until this point it had only been tested on adults under the age of 55. Now older volunteers could be enrolled.

Unlike other vaccines being trialled, the Oxford team had been taking weekly swabs from all volunteers to check whether they were infected but showing no symptoms. If the vaccine could prevent silent transmission it could stop them from unwittingly passing on the virus. "That's a big deal. Because that means the virus could be stopped in its tracks," says Pollard.

Intriguingly, when the trial results came out, there were indications it may partly suppress transmission of the virus. But more evidence is needed.

By the end of the summer, trials of the vaccine were running in six countries including the UK, Brazil, South Africa and the United States. Nearly 20,000 volunteers had been recruited. But on 6 September suddenly everything stopped.

A participant had developed a rare neurological condition.

"In a clinical trial of tens of thousands of people, stuff happens," says Pollard. "People develop illnesses, there will be people who develop cancers and who develop neurological conditions - the difficulty... is to work out whether it's associated with the… vaccine.

An independent safety review did not find any reason to suspect the illness had been caused by the vaccine. But they couldn't rule it out either. The volunteer is still part of the trial and is recovering.

Safety regulators in the UK, Brazil and South Africa gave the green light for the trials to resume within days, but it was six weeks before they were allowed to resume in the US.

All this came amidst a climate of anti-vaccine sentiment - not just online, but with demonstrations taking place around the world.

Transparency and openness about the vaccination process is one way of overcoming such mistrust. This is partly why the extremely busy team of scientists has given the BBC access to their labs over the past year.

In November, two other vaccine trials published their results. They were astonishing. First Pfizer-BioNTech, then a week later Moderna, announced its vaccines were about 95% effective. The team in Oxford were encouraged.

Until then there was uncertainty that any vaccine could work on Covid-19, says Lambe. "There are so many infectious diseases out there that we can't impact."

Finally, on 21 November, the independent data safety committee was ready to reveal the Oxford-AstraZeneca findings. But the results were surprising - and more complex than expected.

Whereas Pfizer and Moderna had one efficacy figure from one big trial each, the Oxford jab ended up with three numbers: 70% overall, with the two full doses giving 62% protection while the smaller group, who were given that initial half dose had the highest protection, had 90%. It was a result no-one had expected.

Crucially, no-one who got the vaccine was hospitalised or got seriously ill due to Covid. Whereas in the control group there were 10 serious cases and one death.

The fact that those who had unwittingly been given the initial half dose from Italy showed stronger protection is intriguing. It may be caused by the immune system being primed more gradually, but the scientists can't yet explain it. Also, all the volunteers in this group were under 55.

Within days, concern was voiced. AstraZeneca accepts that the US regulator, the FDA is likely to hold off approval for now - the company is half-way through recruiting 30,000 volunteers for an American trial.

"We will take them through the data set but my assumption is that they will want to see the US data as well," says Mene Pangalos.

Here, the data is with the UK regulator - everyone is waiting for its decision.

Even at the lowest level of efficacy, the Oxford vaccine passes the effectiveness test with flying colours. The overall effectiveness of 70% is better than most flu vaccines.

Perhaps the main area of debate will be over older adults. There isn't much efficacy data yet from older age groups, since seniors were recruited later. This information will come. There is clear evidence however that the immune response to the vaccine does not decline with age, as it does against other vaccines like flu. This suggests, but doesn't prove, that the jab will offer protection in the elderly.

"Look, I think there is no doubt that we would've run the study a little bit differently if we'd been doing it from scratch, but ultimately we've done as good a job as we possibly can to translate that in to the data set that we can provide to the regulators around the world for approval," says Pangalos.

"The processes we've gone through are the same and just as rigorous as in normal times."

Last week, the Oxford team published an analysis of their trial data in a medical journal - the Lancet, external. This transparency has reassured experts.

While the Pfizer vaccine is already being rolled out, the Oxford-AstraZeneca one has a crucial advantage - its vials can be stored and transported at normal fridge temperature.

This is game-changing, says Sir Jeremy Farrar, the head of Wellcome Trust. "If you have to store vaccines on dry ice that brings additional challenges of how to get it into villages in the UK, let alone villages in sub-Saharan Africa and Brazil."

The UK has preordered millions of vaccine doses which, together, will be more than enough to give every adult in the UK two doses next year. Four million doses of the Oxford vaccine are ready to be handed over to the NHS.

Numbers of orders/pre-orders

100m of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine

40mof the Pfizer-BioNTech

7mModerna

The government hopes by Easter most over-65s and vulnerable groups will be protected. A chance for life to finally return to normal.

How does it feel to have got this far in a little under 12 months?

"It's a relief at this stage, says Gilbert, "that all of the work that people have done during the year and all of the money that's been spent on manufacturing large amounts of this vaccine, is not going to go to waste."

It was worth it! Because we worked really hard. I think we all had a little cry

On the day the results were made public, Green came home to find a colleague had left a magnum of English sparkling wine on her doorstep. But she hasn't had a chance to get together with enough people to drink it yet.

"It's a bit overwhelming to feel that the sacrifices we've made paid off and we did something big. It was worth it, because we worked really hard, I think we all had a little cry," says Green.

Pangalos hopes the vaccine means he will be able to visit his mother in Greece - they haven't seen each other since last Christmas.

The other members of the team haven't seen much of their families either, even when living in the same house. "My son said something the other day that really impacted me," says Lambe. "I was apologising for being late home from work again and he said, 'It's OK mummy, you're doing it for everybody. It's not just me you need to look after.' And that did bring a tear to my eye."

Over the course of the year it's been an emotional journey for everyone working on the vaccine,

But in the end it was the cold, hard science that really made the difference.

"I think science has been the exit strategy for this pandemic and vaccines are at the heart of that scientific endeavour," says Farrar. "It's been remarkable, there's never been a year of progress scientifically like this in my lifetime."

Follow @BBCFergusWalsh, external on Twitter

Viewers in the UK can watch Panorama: The race for a vaccine at 21:05 on BBC One on 14 December, or catch up later online.