Covid: Why won't vaccinating the vulnerable end lockdown?

- Published

- comments

The prime minister says it is too soon to say whether lockdown will be lifted in the spring.

But with the most vulnerable to be offered vaccination by mid-February, what is standing in the way?

The NHS will still be at risk

Lockdown looks to be having an impact on infection levels with the number of new cases starting to fall.

But there are only tentative signs this has filtered through to a slowing of new admissions to hospital.

And even if they start coming down, the overall number of patients in hospital will remain high as patients are being discharged at a much slower rate than they are coming in.

Chris Hopson of NHS Providers, which represents hospital bosses, predicts hospitals will remain under the current "intense pressure" perhaps until the end of February.

With no headroom in the NHS, ministers will be cautious about lifting many of the restrictions, especially with the threat of the new faster-spreading variant.

Vaccine supply is fragile

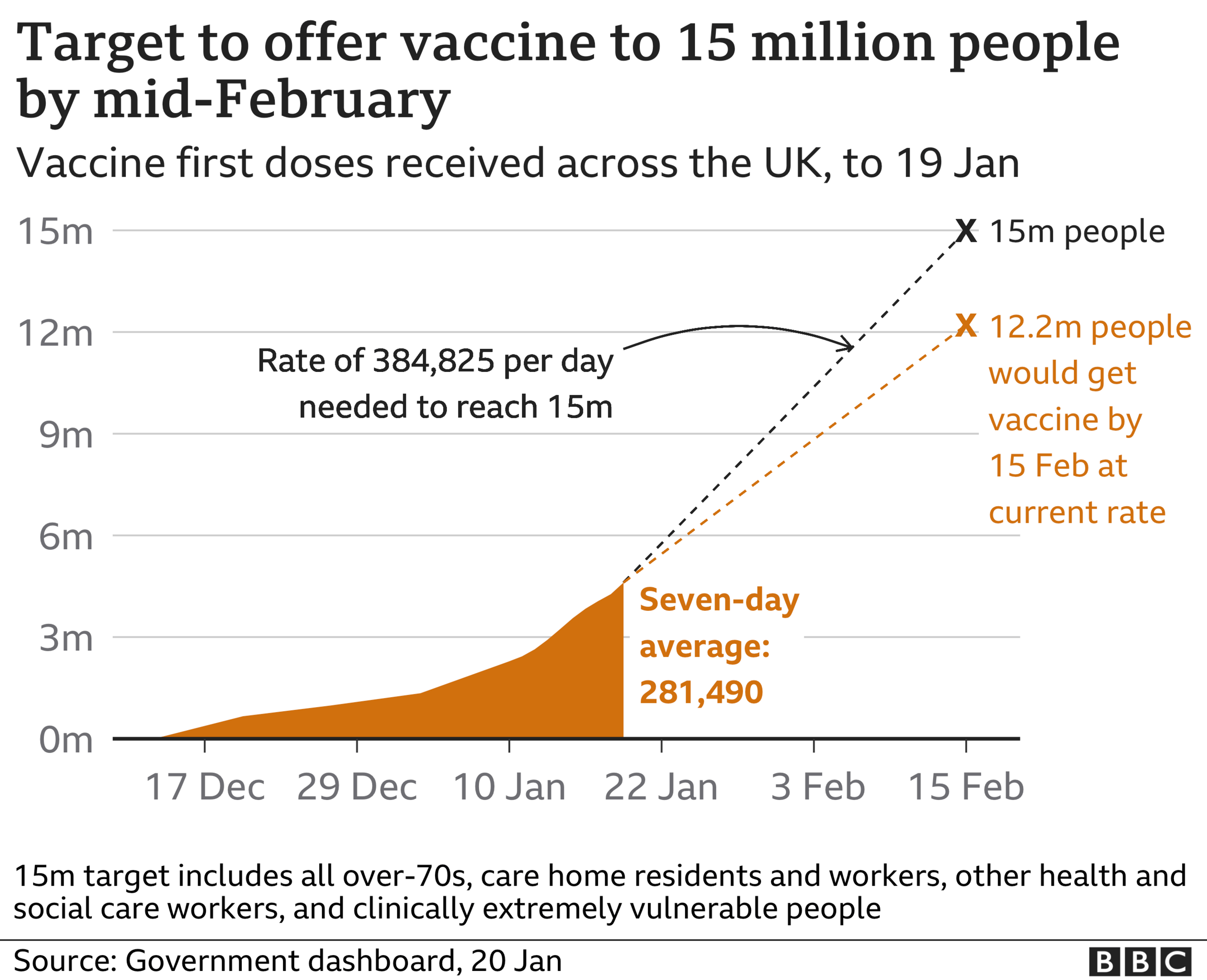

There are no guarantees the government will meet the mid-February target.

The UK has certainly made a good start. Per head of population, only Israel, Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates have vaccinated more.

Over the past week more than two million people have received their first dose.

That puts the government on track for achieving its aim of offering a vaccine to everyone over 70, the extremely clinically vulnerable and frontline health and care workers.

But the supply chain remains fragile. Pfizer has announced a slowdown in manufacturing for the next couple of weeks so it can upgrade its facilities and ramp up production in the spring.

The UK is less reliant on the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine than other countries, as we manufacture the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine here.

There are millions of doses already made but not all of it has been through the final packaging process or safety checks.

Ensuring this happens will be crucial to allowing the NHS to keep its foot on the accelerator, especially as the vaccination clinics will have to start factoring in giving second doses from late February onwards.

Those close to the programme say it will be "touch and go" especially if extra supplies of the Pfizer vaccine do not come back on stream as quick as the company is saying they will.

There will be lots of vulnerable still at risk

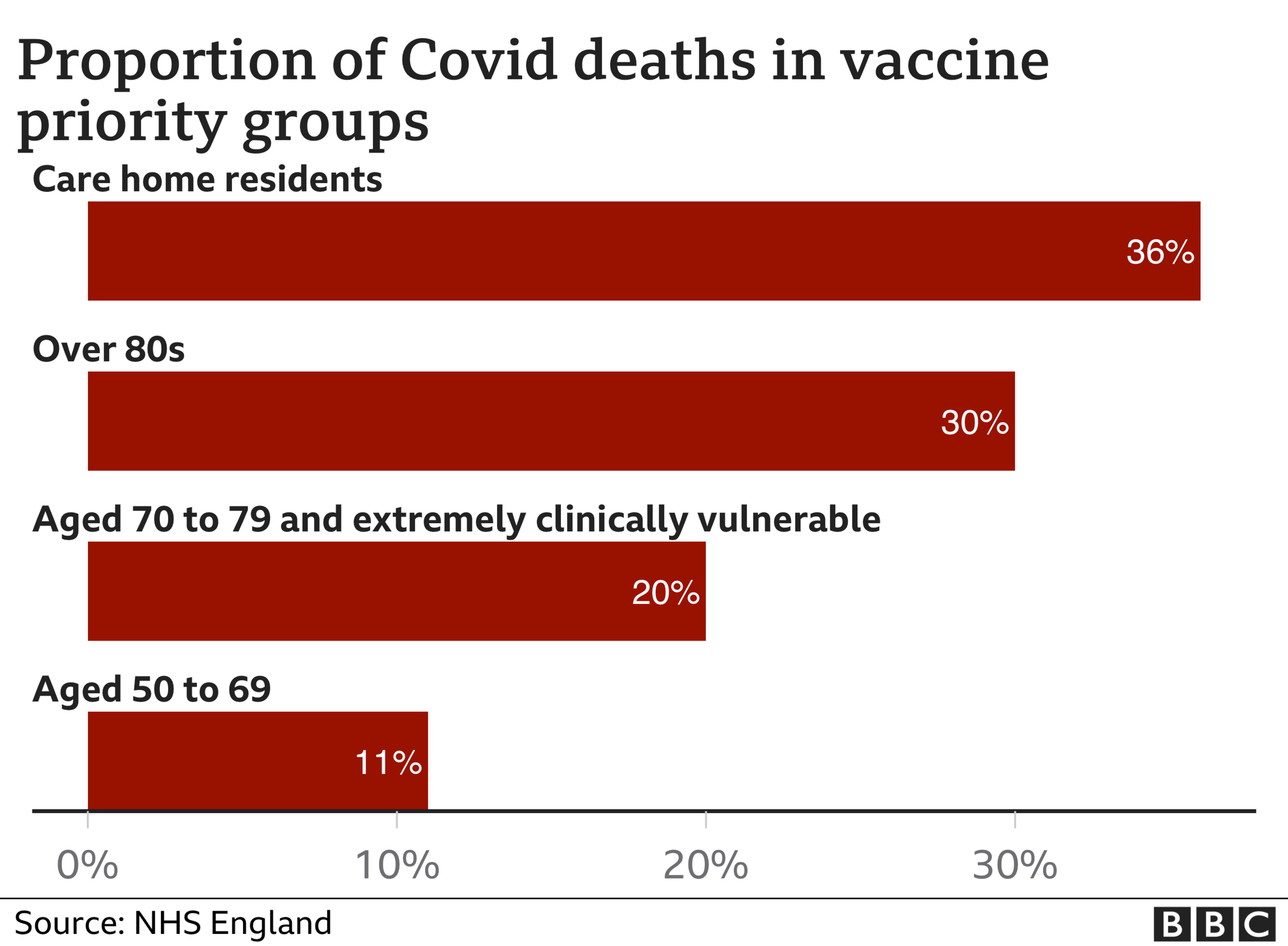

Even if the supply is good, there will still be lots of vulnerable people.

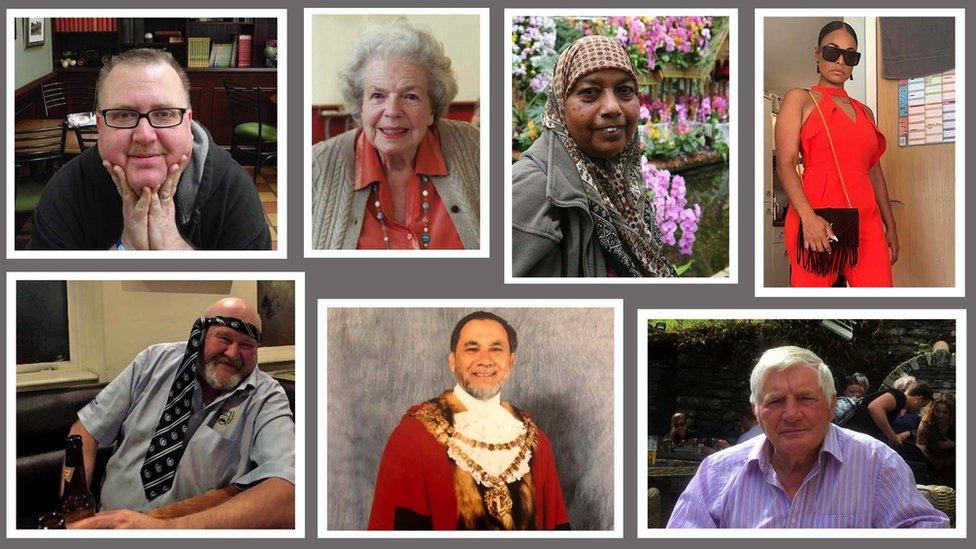

Nearly 90% of Covid deaths have been in the groups due to get the jab by mid-February.

But no vaccine is 100% effective and uptake will not be 100%.

What is more there will still be many vulnerable people in the over-60s age group.

As we get further into spring, everyone over the age of 50, as well as younger adults with health conditions, will be offered a vaccine.

But even that may not be enough, according to some.

Modelling by the University of Warwick suggests that, even with 85% uptake, a complete lifting of restrictions in April could lead to very high levels of deaths.

"Vaccines are not a panacea," says Prof Matt Keeling, who led the research.

And for younger age groups, who are at little risk of dying from the virus, there is still the risk of long-Covid, he says.

Although he acknowledges there is still little hard data to quantify this, some studies have suggested one in 10 suffers long-lasting symptoms from infection.

The big unknown - vaccine and transmission

The factor that could have a significant impact on spread is whether vaccination stops transmission.

The trials showed the vaccines were good at stopping symptoms developing.

But it is not yet known whether those who have been vaccinated will still be able to pass the virus on.

Most people expect there will be some disruption to transmission but how much is not clear - and will not be for months.

Tough judgements will have to be made

But on the other side of all this is the huge impact lockdown has.

The first priority will, of course, be the re-opening of schools.

Russell Viner, president of the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, says everything must be done to make this happen.

He says while schools contributed to spread of the virus, they were not a "significant driver", adding schools were closed for the "benefit of the population" but at great expense to children.

Once schools are open some tough calls will have to be made - and this is where the debate is going to rage.

Backbench Tory MPs are putting the pressure on the prime minister with the Covid Recovery Group calling for a "gradually unwrapping" of society from early March.

In the end, it is going to come down to what society is willing to tolerate.

UK chief medical adviser Prof Chris Whitty has spoken about "de-risking" Covid.

His point is that we will reach a situation at which the level of death and illness caused by Covid is at a level society can "tolerate" - just as we tolerate 7,000 to 20,000 people dying from flu every year.

Sociologist Prof Robert Dingwall, who advises the government on the science of human behaviour, believes that point will be reached sooner rather than later.

"I think we will see a pretty rapid lifting of restrictions in the spring and summer.

"There are some sections of the science community that want to pursue an elimination strategy - but once you start seeing fatality levels down at the level of flu I think the public will accept that."

Related topics

- Published11 November 2020

- Published5 July 2023

- Published5 July 2022

- Published30 April 2020