Coronavirus doctor's diary: Will Covid be with us forever, like flu?

- Published

The antibodies that protect against infection with Covid-19 fade over time, so it's likely that vaccination will not provide a permanent defence. Covid could become an illness like flu, says Dr John Wright of Bradford Royal Infirmary - one that flares up in society at regular intervals, and that people have more than once.

Four million people in the UK have now tested positive for Covid and one of the burning questions they are asking is: will they get it again? Some viral infections such as measles, mumps or chickenpox only infect us once. They trigger an immune response that provides a lifetime of antibody protection. Some viruses such as flu are masters of disguise, mutating rapidly to escape the detection from our immune surveillance. Other viruses like the common cold, and other endemic coronaviruses, have forgettable faces that fade from our immune memory and come back to visit us year after year.

Just before Christmas I wrote about my surprise at having a possible reinfection with Covid. With 100 million people infected worldwide the number of reinfections appeared to be vanishingly small.

As medical students we immerse ourselves in textbooks full of rare and exotic diseases and in our innocence we then spend our early years diagnosing them in all the patients that we see, only to be gently reminded by our teachers that what is common is common. There is an old medical aphorism for this: when you hear hoofbeats, don't look for zebras.

So when I received my positive PCR result, my first instinct was to ignore the zebra and assume that my first positive antibody test, last summer, had found antibodies arising from common seasonal coronaviruses similar to Covid, not from Covid itself.

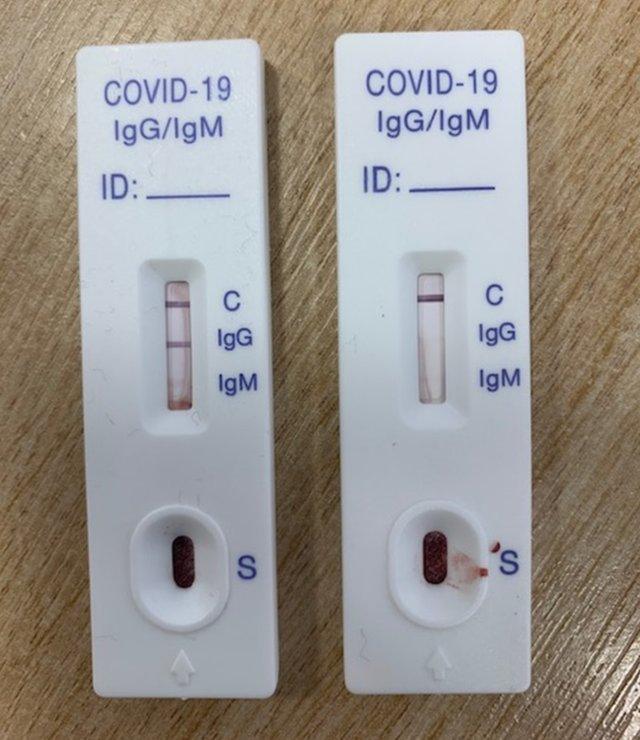

My positive test for previous infection (left) and my colleague Dinesh Saralaya's negative one

Results from the recent national Siren study, external have made me rethink. Back at the start of the pandemic Susan Hopkins, an infectious diseases expert, realised that lots of healthcare workers were getting infected, but the lack of testing availability meant that they did not have confirmed PCR (antigen) results. She was being asked about the risk of reinfection and the possibility of issuing "antibody passports" that would allow people who had recovered from Covid to carry on their normal lives.

She realised that she didn't have the answers and so did what all good scientists do, set up a research study, which got under way in June.

Healthcare workers were among the most at risk during the first wave, so provide a rich soup to study Covid infections. She and her team devised a study of 10,000 NHS staff to follow up for 12 months and as the urgency of the research grew, the study expanded to include 50,000 staff all across the UK.

Those in the study, which is still continuing, get PCR and antibody tests for SARS-CoV-2 every two to four weeks.

Susan Hopkins (left) taking part in a Downing St virtual news briefing on 1 February

In the first set of results, published in January, about one-third of them turned out to have antibodies for the virus, confirming previous infection during the first wave of the pandemic, and the remaining two-thirds had remained clear of infection.

Susan Hopkins found that almost 1% of staff who had evidence of prior infection became reinfected in just the initial five months of the study. Most of these staff had been asymptomatic in their first infection, and so probably had mild infections with immune responses that that faded quickly, but about 25% had a full Covid syndrome and yet still got reinfected. So the severity of the initial illness did not necessarily protect against subsequent infection. Crucially, the study also highlighted that previous infection did not prevent the risk of future transmission of the virus.

The study also found that some people lose their antibodies really quickly, and others lose them more slowly over time.

These results are likely to be a precursor of what happens to our antibodies with vaccines, and so it is becoming clearer that we are unlikely to reach zero Covid. Rather, we will see ongoing outbreaks as our immunity waxes and wanes. One analogy being used foresees the current forest fire of cases becoming a bonfire, then a pile of smouldering embers, and after that just smoke - followed by small fires sparking up, perhaps in the winter months. Previous infection or vaccination will not necessarily protect you.

It may become a feature of lives, like seasonal flu.

Front-line diary

Prof John Wright, a doctor and epidemiologist, is head of the Bradford Institute for Health Research, and a veteran of cholera, HIV and Ebola epidemics in sub-Saharan Africa. He is writing this diary for BBC News and recording from the hospital wards for BBC Radio.

Listen to the Coronavirus Front Line, on the BBC World Service

Or read the previous online diary entry: Why are some of Bradford's elderly residents refusing the vaccine?

This is likely to be an unsettling thought for those who had severe symptoms, for example Jennie Marshall-Hamad, a nurse manager in charge of a female Covid ward. When I last wrote about Jennie, in April, she had sent her four-year-old boy, Zedi, to live with her mother in order to dedicate herself to her work.

A month later she caught the virus. She was unwell for two weeks, and had begun to recover when fatigue and breathing problems set in, keeping her off work for more than three months. She's still attending the long Covid clinic and taking care to get enough rest between shifts.

"I've never been poorly in my life and it's such a big thing that's affected me massively," she says.

Jennie Marshall-Hamad lived apart from her son throughout the first wave

The vaccine provides a degree of confidence. Jennie says she feels safer on the wards, but she remains careful. Like other hospital staff, she takes lateral flow tests twice a week "to reassure us that we're OK" and she still only sees her grandparents - who are in their 90s - from the garden.

Eighty per cent of the staff on her ward have now had Covid, Jennie says, and they will all by now have had the vaccination too.

So how will this combination of immune challenges - infection and vaccination - affect risk of future infection? The Siren study should be able to tell us this, while also showing how single doses of vaccines differ from two doses.

It will also be able to investigate the risk of reinfection with new variants such as the Kent variant and help us understand to what extent our immune response to one type of virus protects us against others.

But it seems highly likely that as more variants emerge across the world, the genetic mutations in the virus will make it a moving target for our body's defence system, and for vaccine manufacturers.

Follow @docjohnwright, external, radio producer @SueM1tchell, external and @hamad_jm, external on Twitter