Covid: UK death rate 'no longer Europe's worst' by winter

- Published

- comments

The UK death rate during the second wave of the pandemic was not the worst in Europe - but it remained one of the 10 worst-affected countries.

By the end of June 2020, the UK had the highest excess mortality in Europe, according to figures from the ONS.

But by December it had been overtaken by Poland, Spain, Belgium, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic and Slovenia.

Nevertheless, the UK had one of the highest excess death rates among people under the age of 65 in 2020 at 7.7%.

Excess mortality is the number of deaths by any cause that happen over and above the average for that time of year.

Meanwhile, the government's separate daily UK coronavirus figures show the number of deaths within 28 days of a positive coronavirus test are continuing to fall.

On Friday, the UK reported a further 101 deaths and 4,802 cases, according to the data., external Last Friday, 175 deaths and 6,609 cases were recorded.

The UK saw 7% more deaths than normally expected during 2020. Within the UK, England's death rate was 8% above expected levels across the whole year, Scotland's was 6%, Northern Ireland 5% and Wales 4%.

The Office for National Statistics figures cover up to 18 December so do not include deaths from this year. About a third of the UK's Covid deaths have happened since then.

Only Bulgaria recorded a higher rate for under-65s - 12.3% - among the countries analysed by the ONS.

Dr Annie Campbell, from the ONS, said the figures showed the pandemic had not "exclusively" affected the oldest age groups in the UK.

For deaths among all age groups Poland ended 2020 with the highest rate (11.6% above the five-year average), followed by Spain (10.6%) and Belgium (9.7%).

England ranked seventh on this list (7.8%) with the UK eighth (7.2%).

All-cause mortality allows countries to be compared more easily, even if they record Covid-19 deaths in different ways. It also reflects the indirect impact of the pandemic, such as deaths from other causes that might be related to delayed access to treatment.

The figures also take account of the average age of a country's population and the average level of deaths in recent years.

LOOK-UP TOOL: How many cases in your area?

LOCKDOWN RULES: What are they and when will they end?

NEW VARIANTS: How worried should we be?

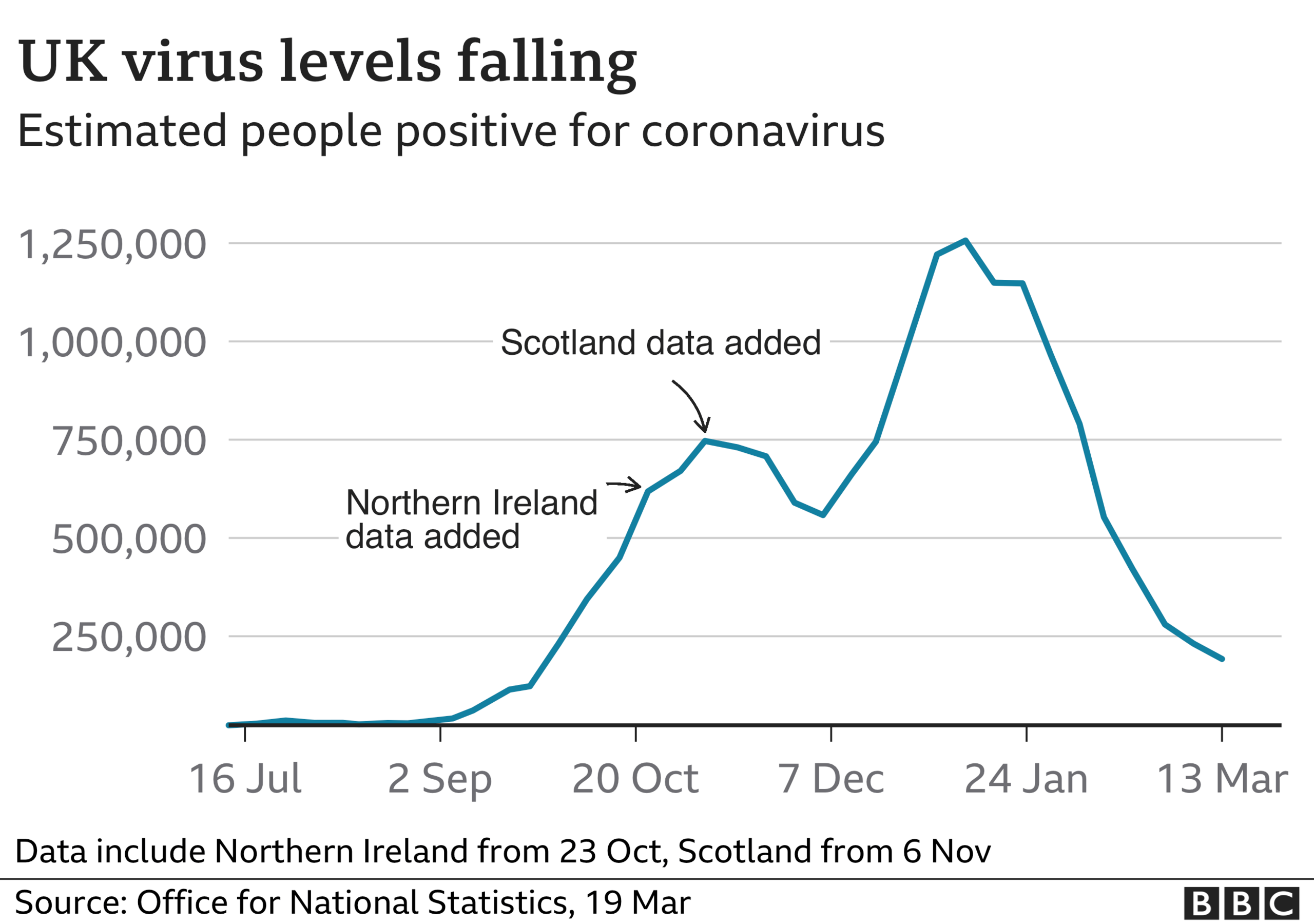

Meanwhile, separate ONS figures suggest infection levels have continued to decrease across England and Wales but have "levelled off" in Northern Ireland and increased in Scotland.

An estimated one in 335 people in the UK had Covid-19 in the week to 13 March, according to the figures, down from one in 280 last week.

In England, the figure is at its lowest since the week to 24 September, when the estimate stood at one in 470.

The ONS results, based on tests from people whether or not they had symptoms, also show:

In England about one in 340 people was estimated to have the virus, down from one in 270 the previous week

In Wales the figure was one in 430, down from one in 365

In Northern Ireland it was one in 315, broadly similar to one in 310 the previous week

In Scotland it was one in 275 - up from one in 320.

The falls in England were driven by falls in the West Midlands, the East, South West and London, the ONS said. The rest of England has seen little change in infection rates and there are hints of an increase in the East Midlands.

The ONS said infections among secondary aged children had decreased and "appear to be levelling" for primary aged children.

However, it said the figures were from the first week since schools returned in England and therefore it was too early to say whether this had influenced infection rates.

The latest R number - which represents the average number people each infected person passes the virus on to - is between 0.6 and 0.9, according to the government's Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies.

Last week the figure was estimated at between 0.6 and 0.8.

When the figure is above one, an outbreak can grow exponentially, but when it is below one, it means the epidemic is shrinking.

It comes as Prime Minister Boris Johnson is to receive his first dose of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine after reassuring the public it was safe.

Several European countries are to resume using the AstraZeneca jab after the European Medicines Agency confirmed it was "safe and effective".

The regulator reviewed the vaccine amid fears about blood clots, but said it was "not associated" with an increased risk of clots and the benefits outweighed any risks.

LINE OF DUTY IS BACK: Get in on the action now

TEACH ME A LESSON: Why do we get ill and what does it mean for our bodies?

- Published26 January 2021

- Published5 July 2023

- Published5 July 2022