Dominic Cummings: What was on his whiteboard?

- Published

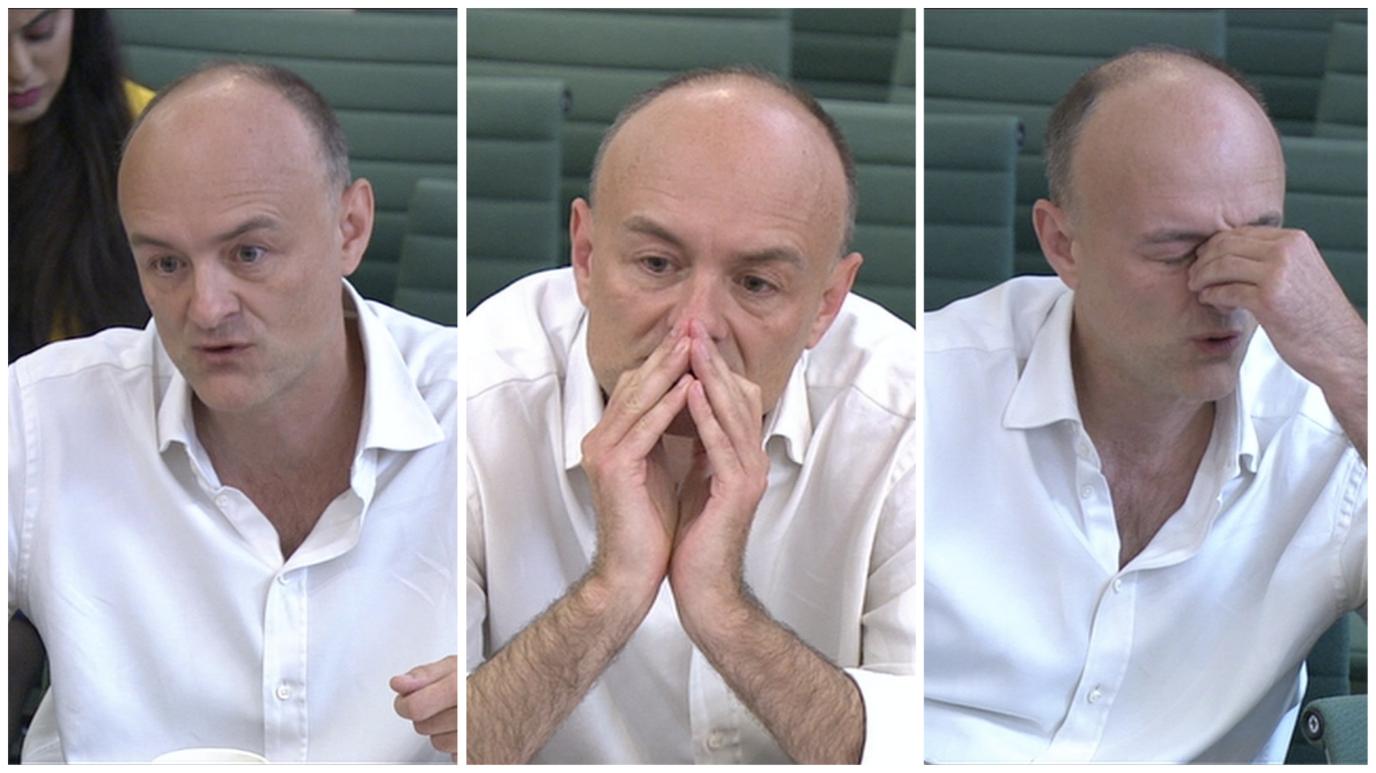

Before giving evidence to MPs on the handling of the pandemic, Dominic Cummings, former adviser to Prime Minister Boris Johnson, tweeted this photo of the whiteboard used to plan the government's early response.

Here, we unpick what it reveals about the priorities, thoughts and policy-by-whiteboard scramble of the government, as it tried to react to the fast-developing crisis.

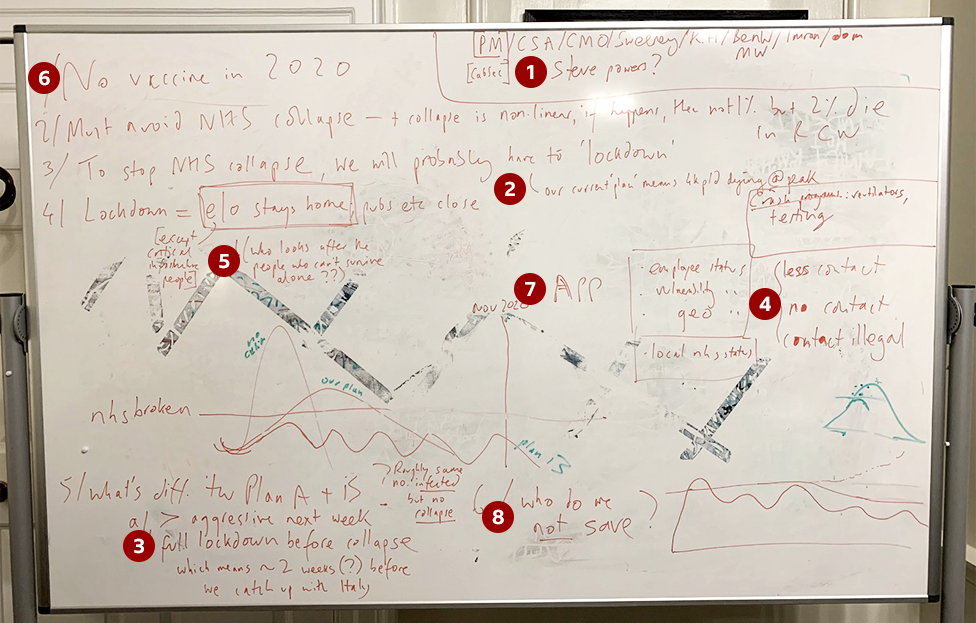

The key names

Some key names of people involved were listed at the top of the whiteboard. Among them were Mr Johnson, chief scientific and medical advisers Sir Patrick Vallance and Chris Whitty, Mr Cummings, and Ben Warner, a data scientist brought in from the Vote Leave campaign.

On 13 March, some of them met to draw up a plan.

The "plan" referred to here is presumably the government's strategy published on 3 March, to "contain", "delay" and then "mitigate" the epidemic. Focusing on hand hygiene and isolating people with symptoms, it only advised social distancing if the virus became "established".

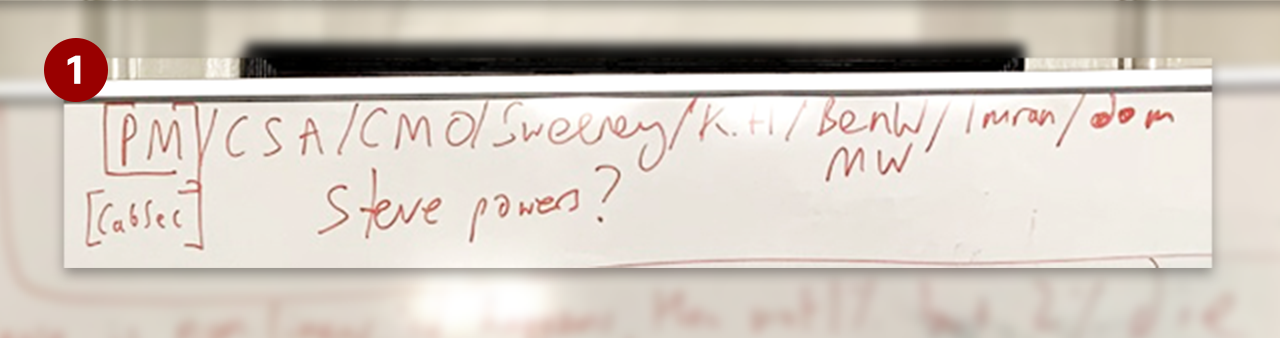

Plan shows 4,000 a day dying

But this scribble on a whiteboard, dated less than a fortnight after the "action plan" was published, seems to capture a moment of dawning realisation. The government's gradual approach - only acting once the data showed cases had already spread - would allow an unacceptable number of deaths.

Not only this, but an estimated 4,000 people a day dying of Covid would spell "collapse" for the NHS, which would be left unable to treat other, non-Covid, patients.

Though the government's plan, dubbed Plan A, would, according to these notes, prevent a huge unchecked spike in deaths, it would not push them down to a level with which the NHS could cope.

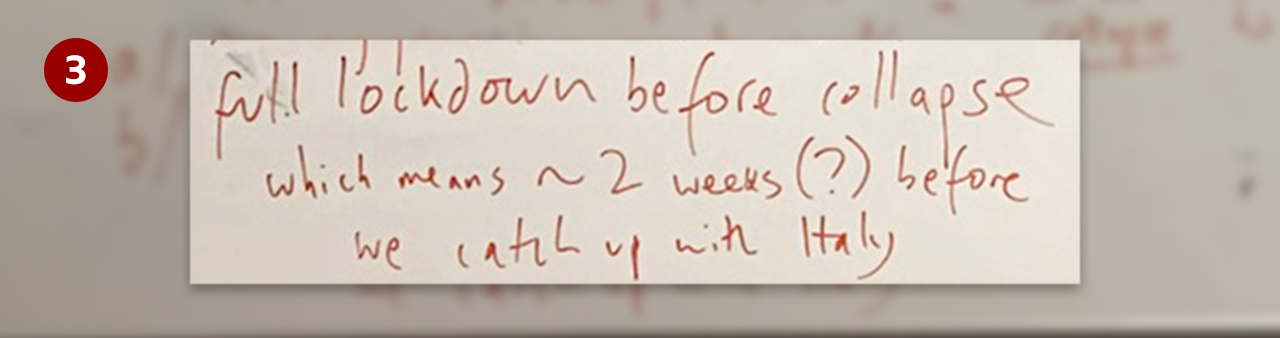

Full lockdown

Plan B - a full lockdown - would leave "roughly the same number" of people infected in the long run, but without the health service falling over.

At this stage the small number of cases in the UK was said to render a full lockdown disproportionate. Mr Cummings now says there was a failure to follow the example of east Asian countries like Taiwan and Singapore, which brought in tough measures before a problem could develop.

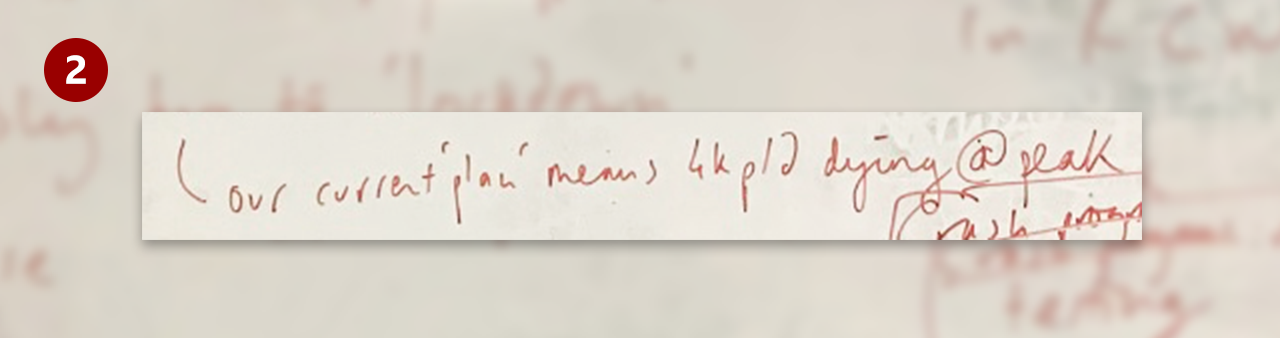

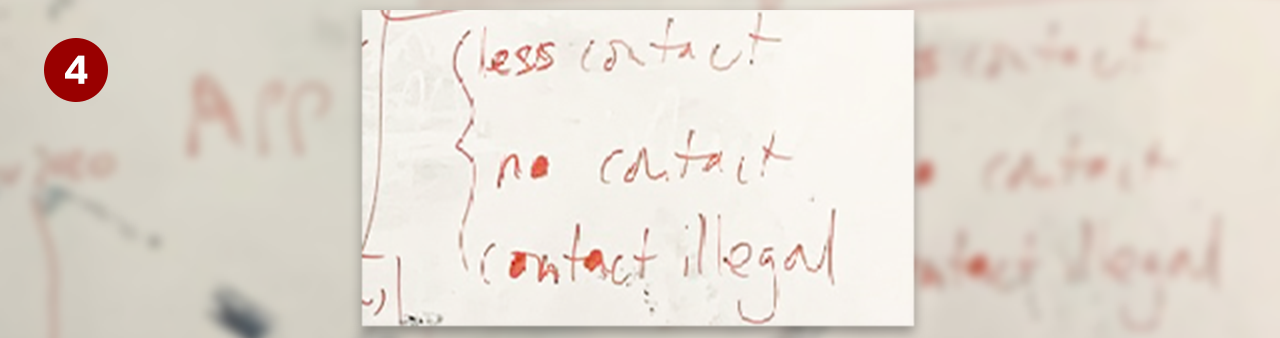

Social contact rules

We can see from this board that on 13 March deliberations were taking place over what potential future restrictions might look like - and what legal force would be put behind them.

And there was an example closer to home of what happened when you didn't act until cases of the virus had spread. Around the time the whiteboard plan was written, experts advising government began to talk of the UK as being two to three weeks behind Italy in terms of cases.

That's the time it took for a handful of cases to turn into a full-blown emergency with hospitals on the brink of collapse. The notes alongside this description of the so-called Plan B - "full lockdown" - make it clear Plan A, the government's current course, wasn't seen as enough to prevent the UK going the same way.

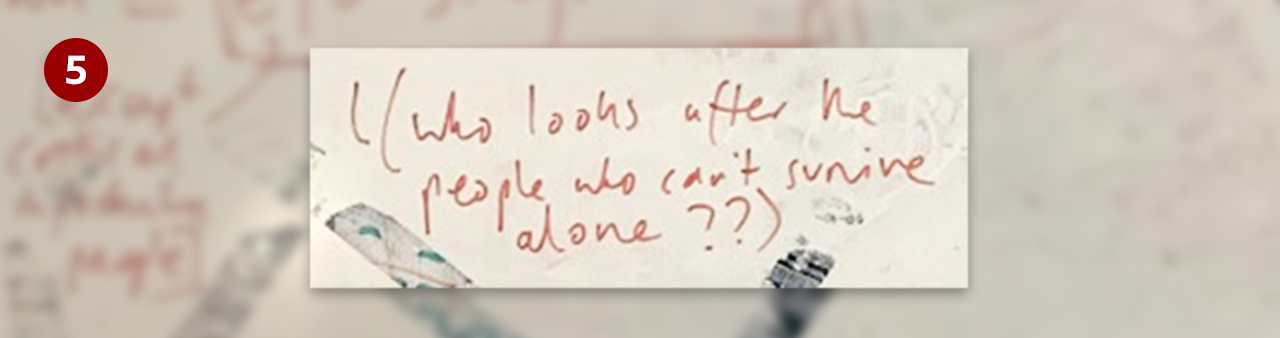

What about shielding?

The decision which would keep 60-odd million people in their homes for the best part of a year and shutter thousands of businesses appears as one sentence on the whiteboard: "Lockdown = everyone stays home, pubs etc close".

But the issue of shielding the clinically vulnerable in their homes, and making sure they could get food and medicine, is no more than a bracketed aside - (who looks after the people who can't survive alone??).

In evidence to the parliamentary inquiry on Wednesday, Mr Cummings said there was no plan for this group of people, with some officials unwilling to publish the number of a newly set-up shielding hotline because there was nothing to offer those who called.

Beneath the statement "everyone stays home", another footnote appears which would prove a matter of life or death for hundreds in essential jobs: "[except critical infrastructure people]".

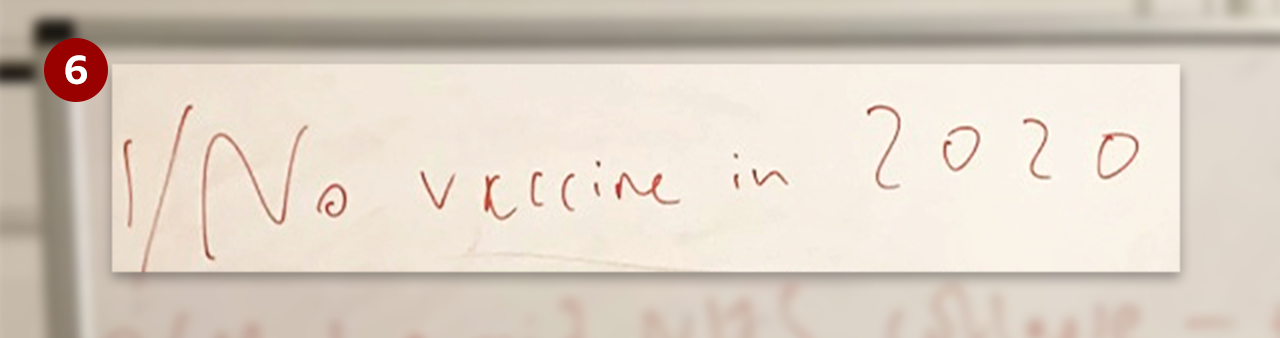

No vaccine in 2020

This assumption - which in the end turned out to not quite be true - was probably influential in decisions around lockdowns. The prospect of an interminable shutdown with no vaccination coming to the rescue may have encouraged advisers to consider other options.

The flawed idea that you could let the virus rip through the healthy population and therefore achieve "herd immunity" - where enough people have protection from the virus and so it dies out - took hold.

It was first explicitly discussed in public by Sir Patrick the day the whiteboard meeting took place. It had been mentioned a few days earlier by David Halpern, a behavioural psychologist with no expertise in immunology.

In reality, by December 2020 only about 10% of people in England had protective Covid antibodies, and nearly 100,000 were dead.

What about the app?

The idea of surviving the year without a vaccine is reflected elsewhere on the board - the need for a "crash programme" to quickly buy in ventilators and build up testing capacity is noted, while just the word "app" floats unattached in the middle.

This context-free reference could be to the NHS contact tracing app, which was seen as playing an important role in helping to control the virus after lockdowns ended - a role it never really lived up to.

Who do we not save?

The final line of the board is the starkest - the question of who would not be saved if the NHS came under threat.

While the NHS avoided being completely overwhelmed, this is not just a hypothetical scenario. Even with lockdown, campaigners have raised the alarm over claims some care homes and learning disability services placed blanket "do not resuscitate" orders on all of their residents. Care home residents were discharged from hospitals to infect their neighbours, in order to free up beds.

Nevertheless, this prospect of doctors having to make snap decisions about who lived or died if oxygen ran out - the horrors currently being suffered in India - may well ultimately have tipped the scales in favour of a lockdown.

Graphics by Tom Housden and Zoe Bartholomew

- Published26 May 2021

- Published26 May 2021