June 21: Why lockdown easing may be delayed

- Published

- comments

Monday was meant to be the moment when the government declared the pandemic was effectively over in England. The plan had been to give a week's notice that all restrictions would end on 21 June.

But the prospect of that happening is now looking increasingly unlikely following the rise of the Delta variant. Behind the scenes, government scientists have been warning ministers this week that caution is needed.

Why do we appear to be stumbling at the final hurdle?

A big surge in infections is coming

It was always expected that infection rates would rise at this point - allowing indoor mixing was the move that provides the most opportunity for the virus to spread.

And with Office for National Statistics data showing eight in 10 adults are currently testing positive for antibodies - a result of both vaccination and previous infection - there are still plenty of susceptible people for it to infect.

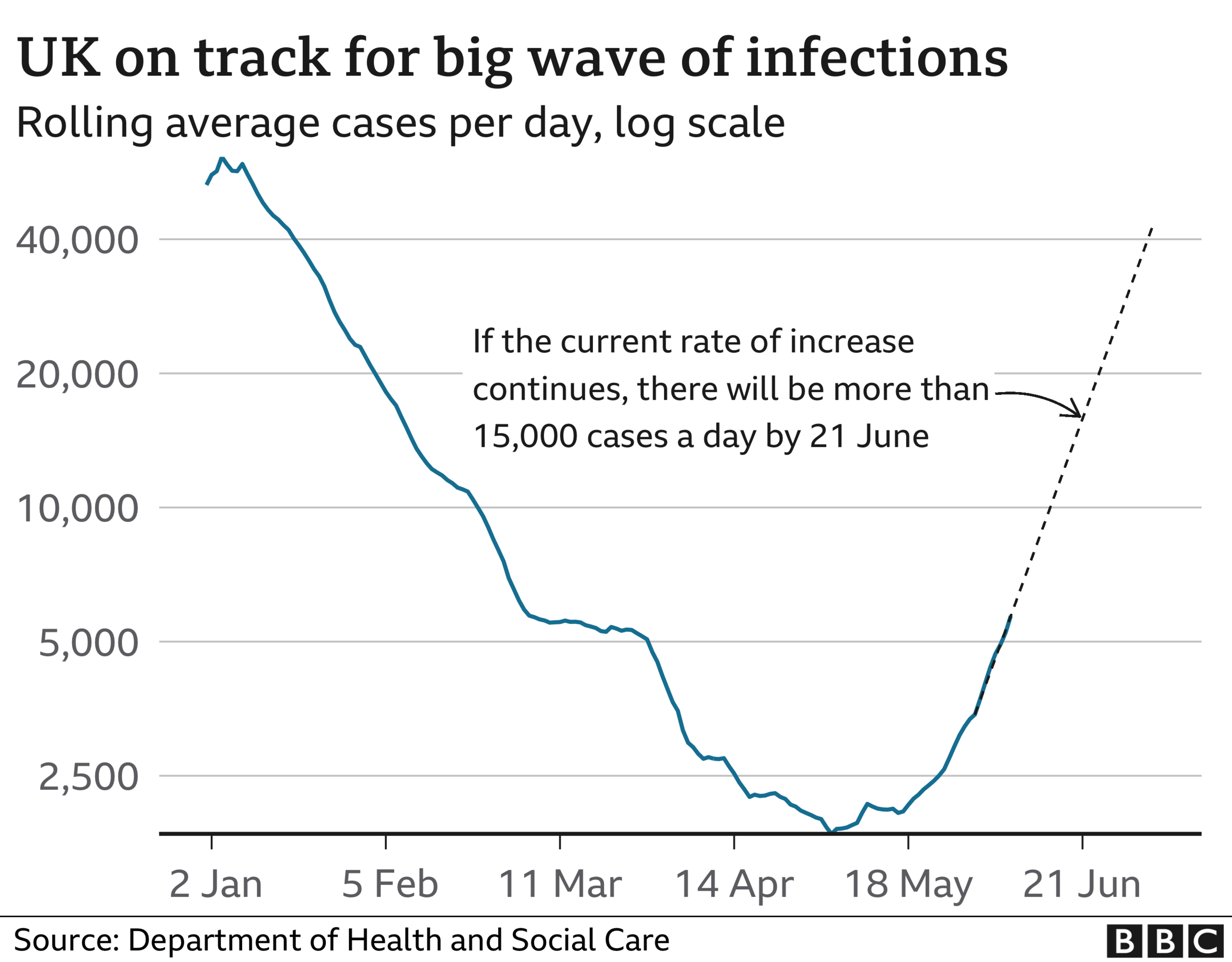

But what has become clear in the past few days is that the trajectory we are on is steeper than many had hoped, because of the more infectious Delta variant, thought to be 40% to 80% more transmissible than the Alpha variant, first identified in Kent.

At the current rate of growth the UK will hit 15,000 cases a day by 21 June and January levels of infections by late July - and that's without the further relaxation of restrictions due, which could drive up cases even more.

"It's very clear where infection rates are heading now - and it's not where we wanted to be or thought we would be just a few weeks ago. That's why we're concerned," says one of the scientists on Sage, the group which advises ministers.

But will hospitalisations follow suit?

What is less clear, however, is what this means for hospital cases.

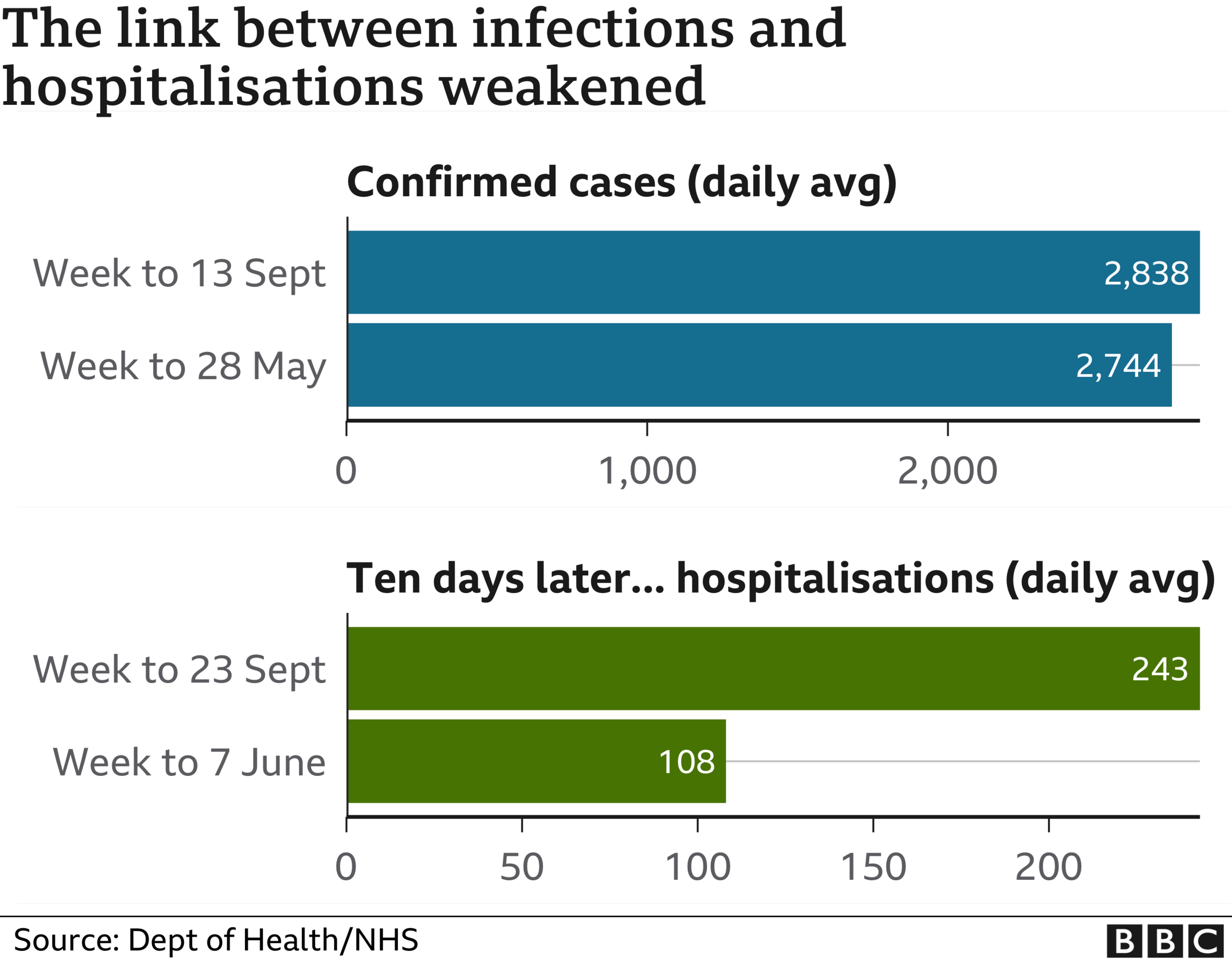

It is often said that vaccination has broken the link between infections and hospitalisations - and if people are not getting seriously sick, then it does not matter if infection levels rise.

But at this stage it appears to have weakened it rather than broken it. Admissions have already started rising, albeit not as fast as they did in September, the last time infections were rising at this rate.

The rate of hospitalisations appears to be less than half of what it was then, although there are only a few days of data to draw on so scientists cannot be certain. This is one of the reasons why they are asking ministers for more time to monitor the data.

But if we assume that link is right, it suggests 4% of cases being identified end up needing hospital treatment. That could equate to 2,000 admissions a day if we do reach January level infection rates - twice what the NHS would normally see in the depths of a bad winter for respiratory illness. A small percentage of a very big number can still be a big number.

However, the data on its own does not tell the full story. There is evidence the people being admitted to hospital are younger and less seriously ill than in previous waves, and so need less treatment and spend less time in hospital.

There seems to be very few doubled-jabbed patients despite those being the most at risk of serious illness - providing further confidence about just how well the vaccines work.

That in turn will mean many many fewer deaths. In a couple of weeks, scientists believe they will be able to give ministers a better idea of what is going to happen than they can now, meaning there will be greater confidence about the impact of a full unlocking.

A delay helps with vaccination

But as well as time to analyse the data, a delay also has the benefit of helping to vaccinate more people.

Evidence gathered by Public Health England shows that getting a second dose is crucial to stemming the spread of the Delta variant.

After one shot, both the Pfizer and AstraZeneca vaccines appear to stop about a third of infections caused by the Delta variant, compared with about half for the Alpha variant.

But for both the protection offered after a second dose remained high - showing that despite the variants every vaccination still brings us closer to ending the pandemic.

Currently just over half of adults are fully vaccinated while another quarter have received one shot. With half a million doses a day being given on average, those figures will be substantially higher in just a few weeks.

"There is a clear public health benefit to a delay as well as providing time to analyse the data," says Prof Neil Ferguson, one of the modellers analysing the figures for ministers.

How Bolton's experience offers hope

People queue for vaccination in Bolton, where there has been a surge in the new variant

Of course, if infection rates keep rising - and that in turn drags up hospital admissions albeit not at the same pace as before - there is a risk that could leave England waiting for months before restrictions end completely.

But there is good reason to hope the rise in cases may be over more quickly than it has been in previous waves and without the need for extra restrictions.

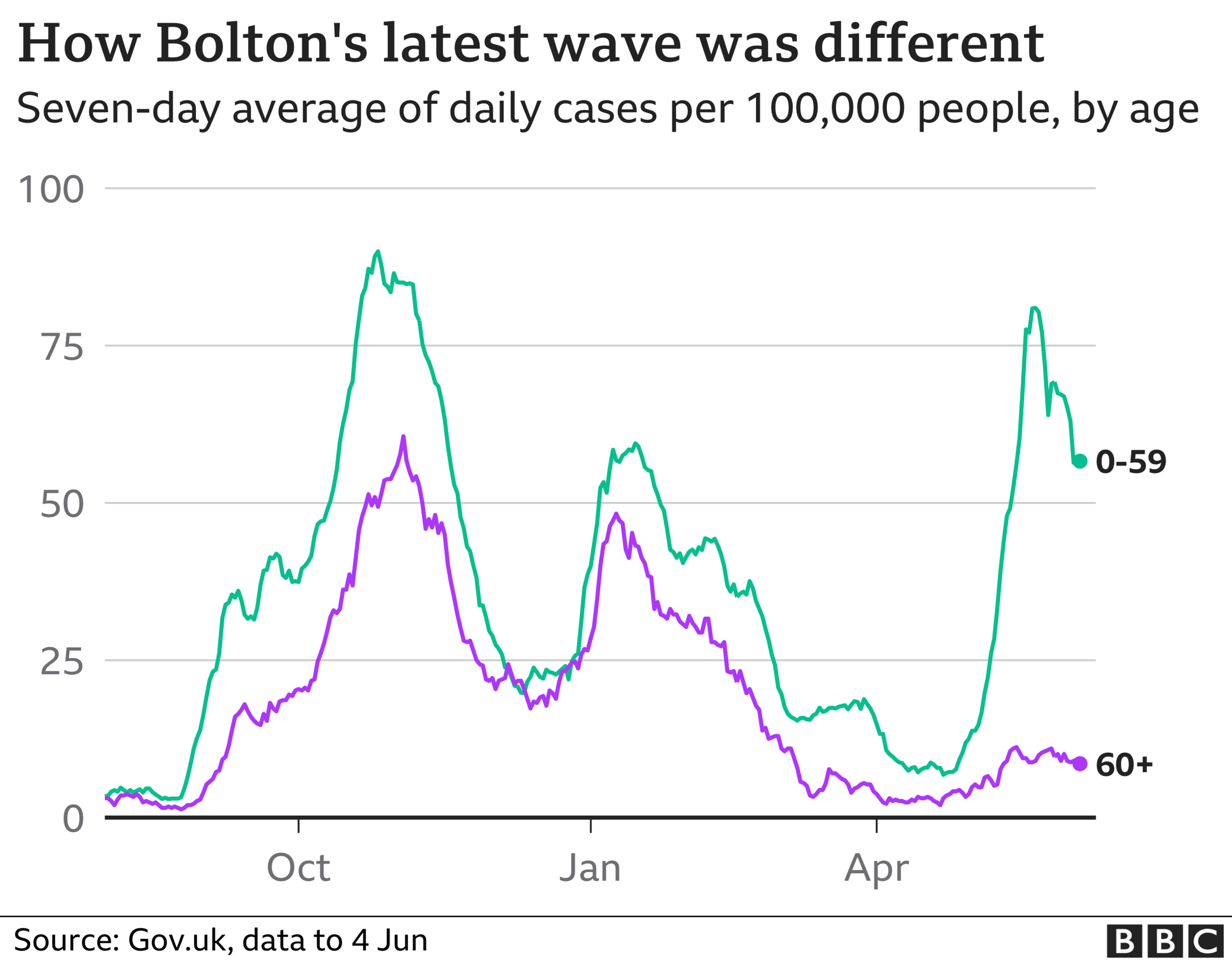

The evidence from Bolton offers some hope of that. Infections started rising rapidly in early May as the Delta variant took hold.

The wave though was quite different from what went before - with very low numbers of over-60s, the group that was mostly double-jabbed by that point, infected.

Infections spread quickly through younger age groups, but soon stopped.

Changes in behaviour, surge testing and the push on vaccinations that have taken place will have played a role, but so too did the wall of immunity the virus came up against.

Dr Adam Kucharski, an infectious diseases expert from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, believes infection levels may not take off significantly in some areas because of their high levels of vaccination.

"I think there will be quite big differences in infection rates between areas. In communities where immunity levels are high and contacts low, we may not see infection rates climb that much."

A delay to the complete ending of restrictions does not mean it will never come.

Follow Nick on Twitter, external

Related topics

- Published5 July 2023

- Published5 July 2022

- Published30 April 2020