Covid: Will 19 July unlocking gamble pay off or backfire?

- Published

- comments

Nearly all remaining Covid restrictions are coming to an end. But with infection rates and hospital admissions already rising sharply, it is a significant gamble.

One expert likens what is being done to taking the "control rods out of a nuclear reactor".

"This is going to make things worse than they are now and we don't know when it will peak," says Loughborough University data analyst Dr Duncan Robertson.

And that in many ways goes to the heart of the issue.

This is our first "natural wave" of Covid - all the others have been brought to an end through lockdown and restrictions. The plan is for this one to exhaust itself. So predicting what will happen is much more difficult.

The move has been given the personal backing of chief medical officer Prof Chris Whitty and a number of the scientists advising him. Infection rates were always going to rise at this stage of the roadmap - more mixing means it is easier for the virus to spread.

But with significant levels of immunity from vaccination and natural infection the hope is spread of the virus will be brought under control in the coming weeks.

Waiting longer could make things worse

Some have suggested the government should wait longer before taking this step. But infections are already rising so that will not halt the rise.

And, according to Prof Whitty, were we to wait any longer, there is a risk the peak of infections this summer wave could be pushed to the autumn, which could make things worse with flu and other viruses circulating.

But that does not mean government scientists do not have concerns. Behind the scenes, they have been questioning the policy on face masks, in particular, after ministers made big play of the fact mask-wearing would no longer be legally required. Not because it will dramatically alter the course of rising infections, but because of the message it sent out - that controlling infection no longer mattered.

This has led to a definite change of approach with ministers now stressing the need to keep wearing masks in crowded indoor places.

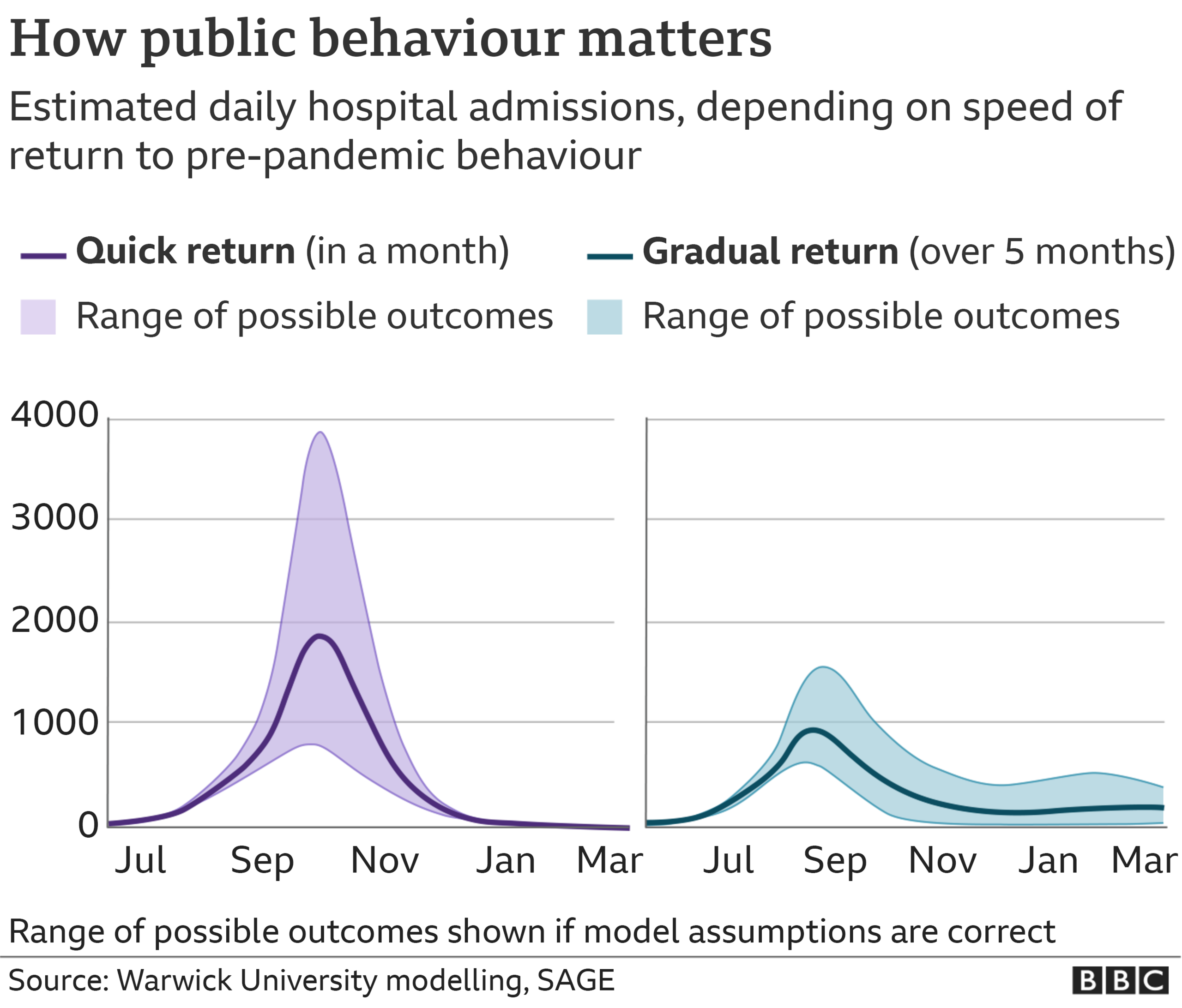

The reason is clear from the results of the latest modelling to be released. It looked at the impact of people returning almost immediately to normal behaviour, and compared it with a gradual resumption over months.

The results estimated the gradual approach could halve the summer peak and avoid what is called an overshoot - whereby the surge in cases means greater numbers become infected than need be, before this summer wave peaks. The modelling shows this is much more important in reducing the peak than simply delaying the lifting of restrictions.

It is why Prof Whitty has also referred to the importance of the public "going slowly" in the way they embrace new freedoms.

Prof Matt Keeling, a modeller at the University of Warwick, has gone even further. "If there is one message - the public is going to control the trajectory we are on," he said.

But this is just one of many unknowns, which explains the huge range around the central estimate that hospital admissions will peak this summer at 1,000 to 2,000 a day. (The winter wave just gone hit 4,000 in comparison.)

The cost of the summer wave

And if this does happen, it will come at a significant cost. While the vaccination programme has reduced the number of Covid deaths 10-fold, there could still be 100 to 200 deaths a day. About half of those are expected to be in unvaccinated people. It will also cause major disruption to the NHS. To put those summer figures into context, hospitals would expect to see about 1,000 admissions a day in the depths of winter, for all types of respiratory infections.

Will 19 July unlocking gamble pay off or backfire?

"We would get through it as we have before," says Dr Alison Pittard, of the Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine. "But it would be at the expense of elective care and other treatments."

Another consequence will be more people struggling with long Covid either because it takes them time to recover after being hospitalised or from persistent symptoms, such as fatigue and brain fog, which for a small minority appear to happen after milder illness.

Immunity will be way out

But, in the end, unless restrictions are re-introduced, this wave is only likely to come to an end when the wall of immunity - from vaccination and natural infection - is high enough. And when that happens, England could find itself in the very strong position, Sir Patrick Vallance, the government's chief scientific adviser, hinted last week. He said we were reaching the level of immunity where "big waves" may be in the past.

This does not mean herd immunity - given how infectious the Delta variant is and the changing nature of the virus, many experts now question whether this will be possible. Covid, they believe, is going to be around forever.

Instead, scientists expect some sort of equilibrium will be reached, whereby the R number, the average number of people an infected person passes the virus on to, will fluctuate around one.

This will see more manageable waves ebb and flow. And with vaccines offering good protection against serious illness, society will be more willing to tolerate the burden.

After all, in the most recent bad winter - 2017-18 - there were 300 to 400 flu deaths a day at the peak, external, more than is being predicted for this summer's Covid peak.

Will we get there in the coming months? It is, one of the key government modellers told me, really too close to call.

Follow Nick on Twitter, external

Are you still shielding and are concerned that restrictions are lifting in England? Or are you in favour of the decision taken? Share your experiences by emailing haveyoursay@bbc.co.uk, external.

Please include a contact number if you are willing to speak to a BBC journalist. You can also get in touch in the following ways:

WhatsApp: +44 7756 165803

Tweet: @BBC_HaveYourSay, external

Please read our terms & conditions and privacy policy

If you are reading this page and can't see the form you will need to visit the mobile version of the BBC website to submit your question or comment or you can email us at HaveYourSay@bbc.co.uk, external. Please include your name, age and location with any submission.

- Published5 July 2021

- Published5 July 2023

- Published5 July 2022

- Published30 April 2020