Covid: How vaccines changed the course of the pandemic

- Published

Margaret Keenan receiving the first approved vaccine outside of a clinical trial on 8 December last year

Exactly a year ago the first approved Covid vaccine was given outside of a trial.

The recipient was 91-year-old Margaret Keenan who received her jab at University Hospital Coventry.

Since then nearly 120 million jabs have been given in the UK, and more than eight billion across the world. Those vaccinations have changed the course of the pandemic.

Going into arms quickly

The UK had one of the fastest rollouts of Covid vaccines globally.

The approval of the Pfizer jab was quickly followed by the green light for the vaccine produced by AstraZeneca.

A third jab, made by Moderna, has also been used, although in much smaller numbers.

By the end of June, all adults had been offered a first dose and then by the end of September, a second dose. At that point people had also started being invited for booster jabs.

As well as reducing the risk of catching the virus, the vaccines also reduce the risk of an infected individual spreading the virus.

Coping with variants and waning

The vaccines, though, have had a lot to cope with - in particular new variants. But they have held up well.

The vaccines being used were based on the original Wuhan strain of the virus.

But by the time rollout began in the UK, a new faster-spreading variant, known as Alpha, had taken over.

That was then displaced by an even more infectious variant, Delta, which also had the ability to evade some of the immune response triggered by vaccines.

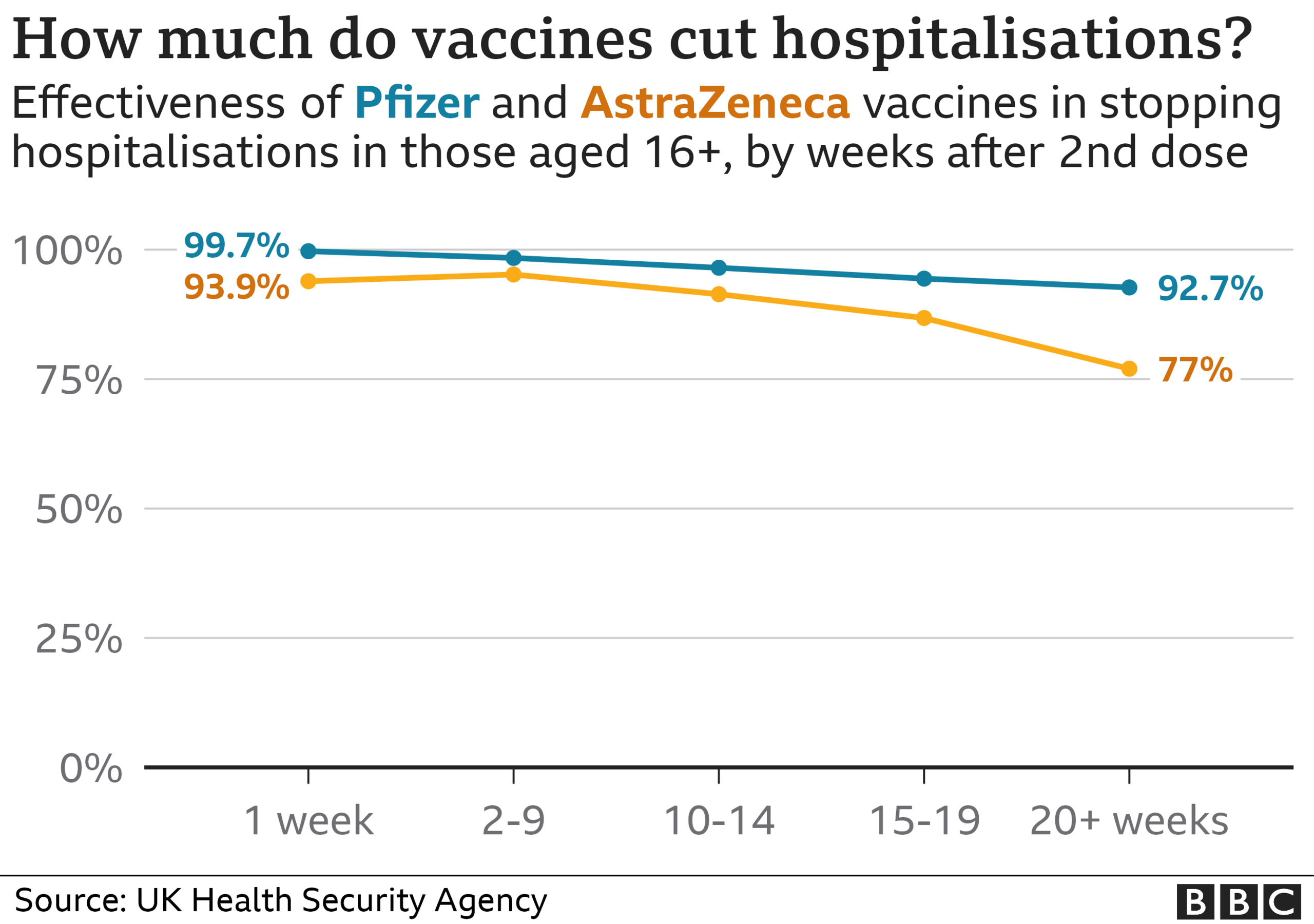

The effect of the vaccines also wanes over time, particularly in terms of preventing infection.

But despite all this, the evidence gathered in the UK in the autumn showed both the main vaccines in use remained very effective at preventing hospital admissions.

Saving thousands of lives

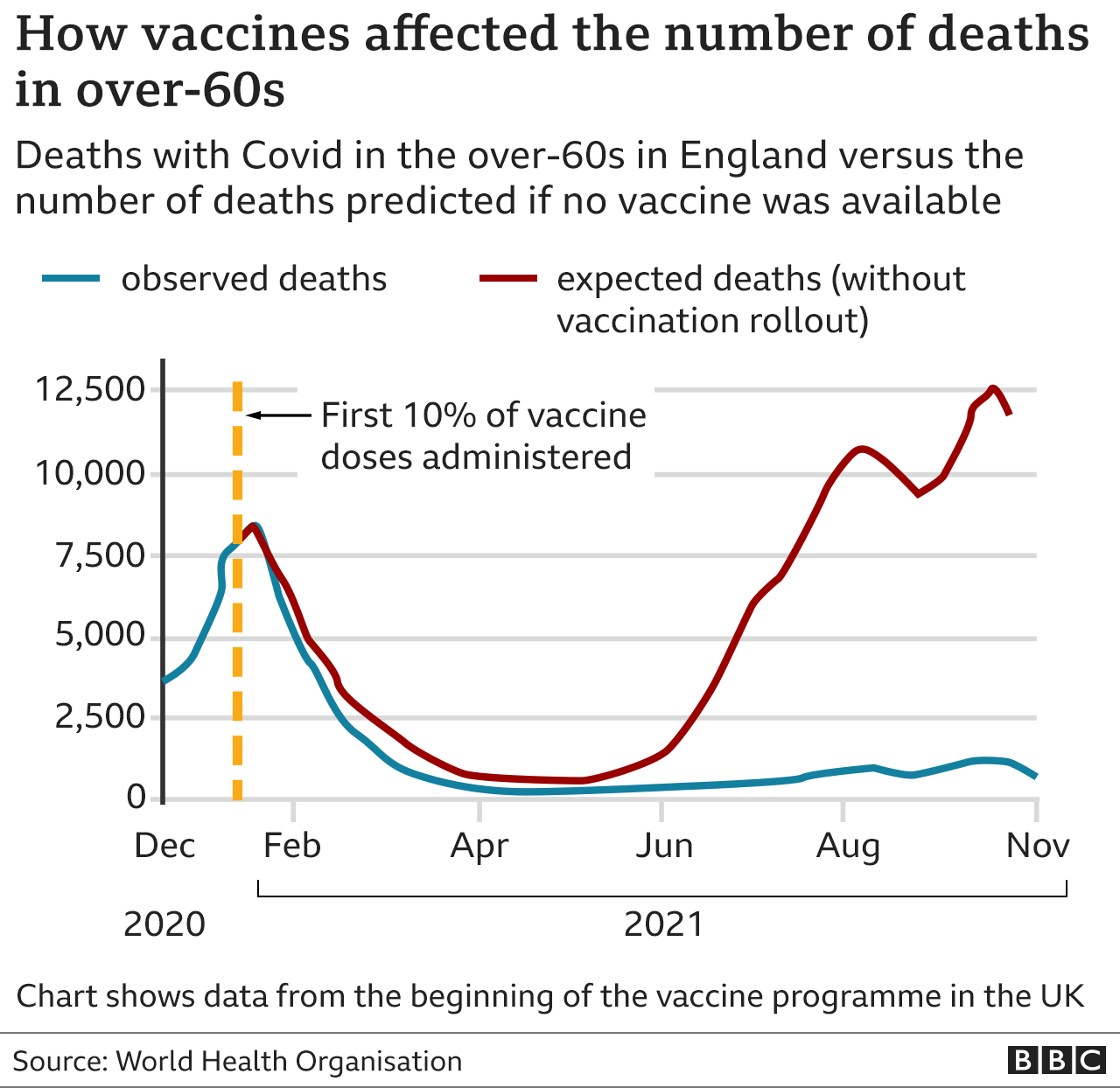

The ability to stop serious illness has saved countless lives as societies have opened up.

Researchers at the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control and World Health Organisation, external have been modelling how many deaths have been prevented, based on the infection rates seen as countries have relaxed restrictions.

They estimate vaccines saved 157,000 lives in England alone, and more than 470,000 across the 33 countries in Europe which were studied.

Researchers called the Covid vaccines a "marvel of modern science".

They have essentially transformed a continent reliant on lockdowns to one that has cautiously started returning to normal.

But the vaccines are now facing perhaps their biggest challenge yet - Omicron.

There are fears the new heavily mutated variant could get around some of the defences built up by the vaccines.

If the worst fears are realised, the vaccines may need to be updated. But many experts expect that won't be necessary and they will still provide pretty good protection, and help prevent severe illness.

Multiple vaccines now in use

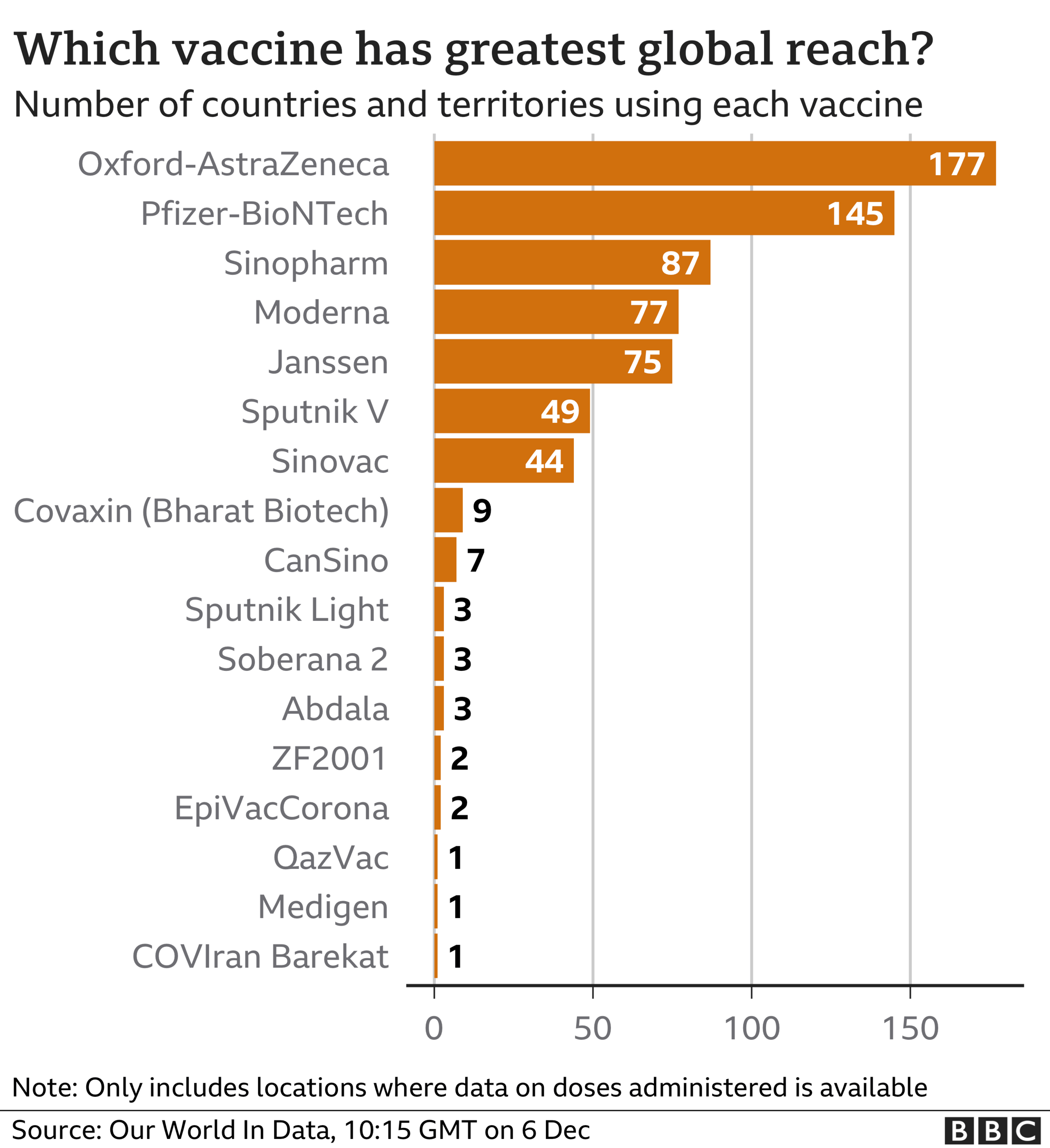

While the UK and much of Europe has been largely reliant on three vaccines, there are actually 17 recorded in use across the globe.

Pfizer and AstraZeneca have been by far the most commonly used.

The Russian-made Sputnick V and China's Sinopharm have both been used heavily, particularly in South America.

Some countries, including Iran with its COVIran Barekat and Kazakhstan with QazVac, have produced home-grown vaccines that have only been used on their own populations.

Poorer countries benefiting the least

But while vaccines have come to the aid of Europe and some other wealthy nations, the same cannot be said for the developing world.

More than 50 countries missed the World Health Organization deadline to have 10% of their populations immunised by the end of September.

Most were in Africa where there are still five countries with fewer than two doses administered per 100 people.

Supply has been a big issue. The biggest problem facing the vaccine-sharing Covax scheme was its dependence on the Serum Institute of India, the world's biggest vaccine-maker.

India halted vaccine exports in April in response to its own urgent needs, and other manufacturers faced issues ramping up production.

But hesitancy also plays a role. There have been cases of African countries having to throw away doses because they have not been used by their expiry date.

At the current rate of rollout it will take another five months to get three-quarters of the world vaccinated with at least one dose.

This can have significant consequences not just for the populations in the countries with low levels of vaccination, but also for the rest of the world.

The more virus that is circulating, the higher the risk of new variants.

Follow Nick on Twitter, external.

Data visualisation by Rob England and Sandra Rodriguez Chillida

LOOK-UP TOOL: How many cases in your area?

YOUR QUESTIONS: We answer your queries

VACCINE: When will I get the jab?

NEW VARIANTS: How worried should we be?

- Published15 September 2021

- Published11 November 2020

- Published5 July 2023

- Published5 July 2022

- Published30 April 2020