Omicron: Why tougher Covid measures may not be worth it

- Published

Heath experts are encouraging mask wearing

Infections caused by the new variant Omicron are rising rapidly, doubling every two to three days.

Modelling is warning hospital admissions could rise sharply.

Ministers across the UK are under pressure to bring in tougher measures.

There are strong arguments for those, but there are also reasons why trying to do more to suppress Omicron may not be worth it.

Omicron may be milder

Much has been made of suggestions that this variant is causing milder illness. In South Africa, reports are emerging that people are not as seriously ill in this wave as they were in earlier ones.

There is still uncertainty about this. But it is logical. Not because the virus has changed to become less severe, but because reinfections and infections post-vaccination are likely to be milder.

The immune system now recognises this virus and while it may not be able to prevent infection, it knows how to fight it.

"The balance of evidence," says Prof Paul Hunter, an expert in infectious diseases at the University of East Anglia, "certainly points to that."

Booster jabs have been shown to be effective against Omicron

If so, that puts the UK in a strong position to be able to deal with this wave.

Around 95% of the adult population has some immunity to the virus either through infection or vaccination or both, according to the Office for National Statistics.

Research by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, external published at the start of winter before Omicron emerged said such high levels of immunity meant we had the smallest pool of vulnerable people in Europe.

On top of that there is now the impact of the rapid rollout of boosters, which research suggests are vital to blunting the impact of Omicron.

Around 60% of those eligible have had one including nearly 90% of the most vulnerable.

Taken together, it is a very different picture from last winter when the lockdown allowed the rollout of the vaccination programme to get going and provide protection to the majority of the adult population.

Prof Hunter says the combined level of vaccine-induced and infection-induced immunity in the population now means the case for extra restrictions beyond what has been announced is much weaker than it was previously.

Tougher measures, he says, will not stop the epidemic, they will just extend it. "If you are waiting for vaccines or better treatments, suppressing the virus could be an advantage - but it's hard to see the argument for that now."

Protecting the NHS from being completely overwhelmed would, of course, necessitate action.

But Prof Hunter says he is "cautiously optimistic" that will not happen, believing the public will naturally start to curb their behaviour given the concern being expressed about Omicron.

And, once we get through this, he believes we will be in a much better position. "There will be other variants but exposure will have built up our immunity even further. We will see milder disease - until eventually it is something like the common cold."

So what are the chances of the NHS buckling in the coming weeks? While there are strong grounds to hope the proportion of infections leading to a hospital admission will be lower than it was previously, if infection levels rise too high the absolute numbers could still be much bigger than they are now.

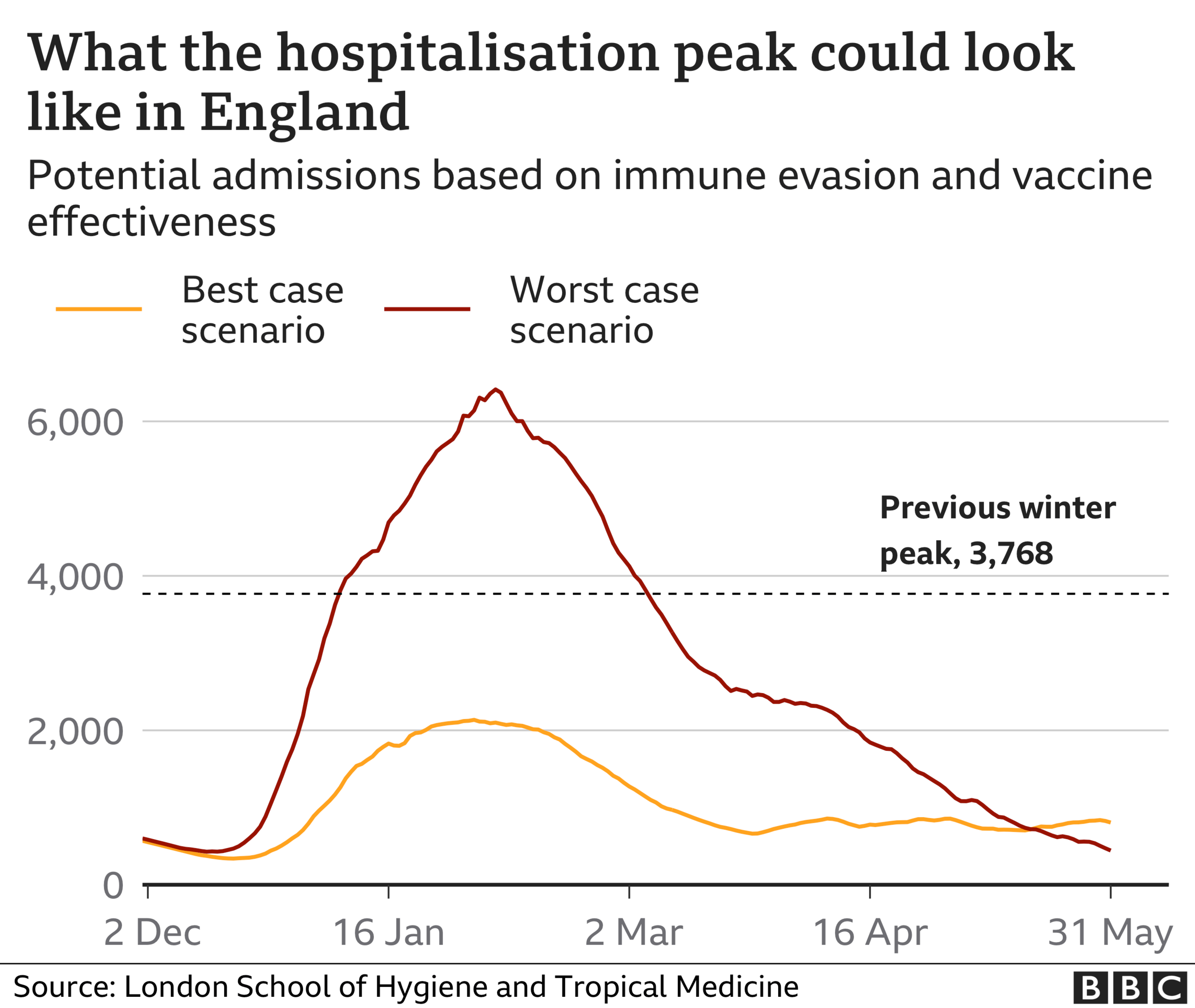

This much can be seen from the modelling published by the LSHTM.

It sets out what could be called the best and worst-case scenarios.

The best would see admissions peak at just over half the level of last winter, the worst would see admissions edge towards double.

Dr Raghib Ali, a clinical epidemiologist at University of Cambridge, and a front-line doctor, says given the levels of immunity in the population there is no need to panic yet.

"We need to keep calm," he says, and wait until we start getting a clear idea of what is happening with hospital admissions. "We should know soon."

He admits some further action may be needed to "flatten the peak" to stop hospitals getting overwhelmed.

But he believes the Christmas break and January may come to our aid as workplace mixing and travel reduces, although he stresses that taking precautions such as regular testing, mask-wearing and ventilating indoor spaces is essential.

"We have to be realistic, we are not going to stop Omicron."

Suppress it too much and arguably it will just delay deaths and serious illness - and may cause more overall harm than good when you consider the wider impact on health, education and the economy, he says.

NHS 'beyond full stretch'

The key, though, will be that the NHS can keep delivering care to those who need it.

Chris Hopson, of NHS Providers, which represents hospital bosses, says he is "very concerned" given what has already happened with patients facing longer waits for ambulances and A&E.

Care is already becoming "less safe", he says, and the service is being forced to run "beyond full stretch".

It is clear the peak in admissions needs to be towards the lower end of the modelling estimates for the NHS to have a chance of getting through the next few months.

And even if the wave of infections does not cause enough serious illness to overwhelm the NHS, University of Reading scientist Dr Simon Clarke says there could still be significant societal problems.

"Mass sickness of people who are not ill enough to end up in hospital, but who need to convalesce at home, could deliver a substantial shutdown of public services and slowing of economic activity," he says.

How long could this last? The UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) believes we are likely to be looking at a period of four to eight weeks where we will be battling the acute stage of the Omicron surge.

It will be, says Dr Susan Hopkins, UKHSA's chief medical adviser, a "very difficult" period.

Related topics

- Published15 September 2021

- Published11 November 2020

- Published5 July 2023

- Published5 July 2022

- Published30 April 2020