Omicron stats are huge, but look beyond them

- Published

- comments

In London, hospital admissions may have peaked

Covid infections have risen to unprecedented levels in recent weeks because of the Omicron variant.

But, as early evidence suggested it would, this variant is causing milder illness, for now at least.

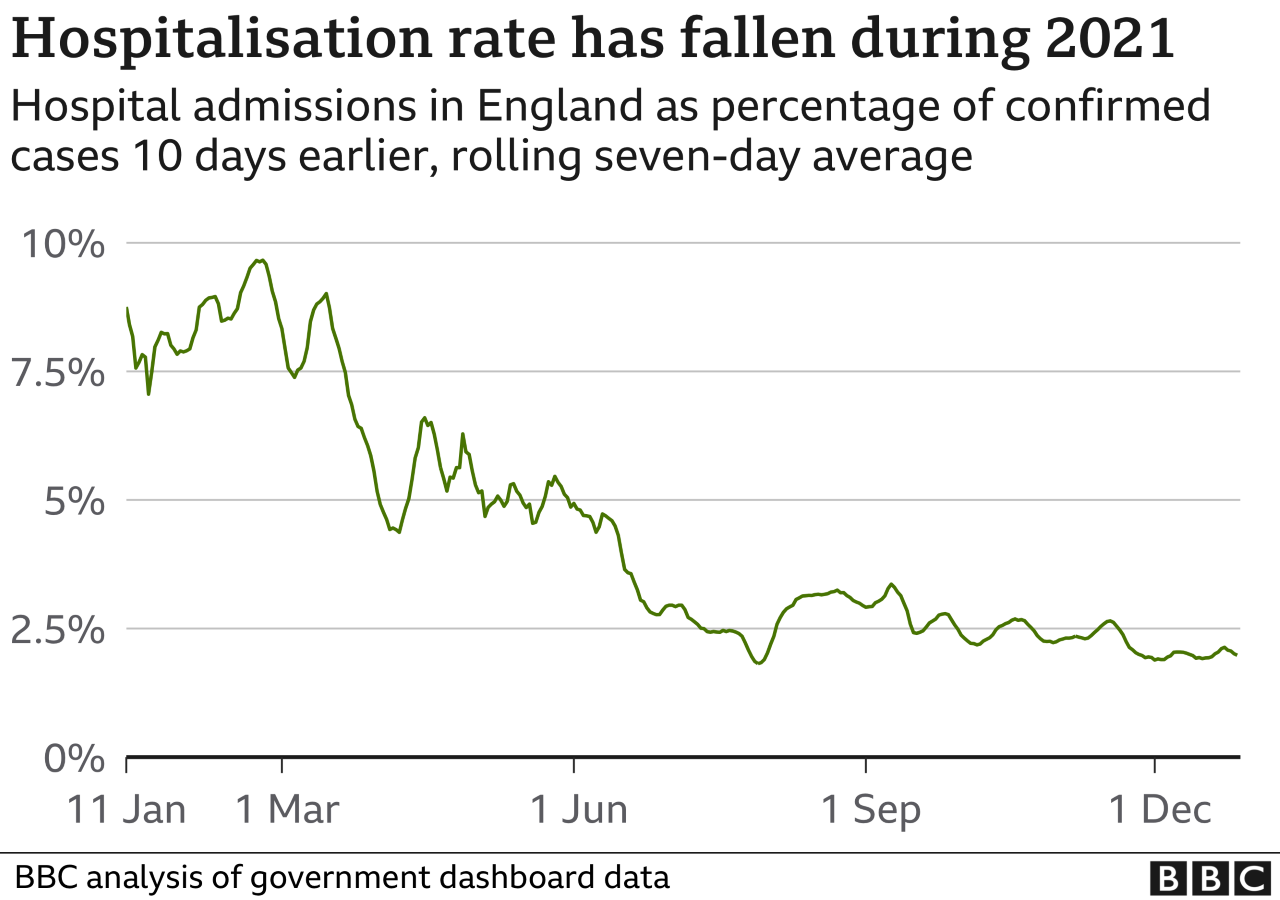

A fall in the proportion of detected cases ending in hospital is a good sign of this. It is now five times lower than it was a year ago.

This is largely thanks to a huge amount of immunity that has built up across the population either through vaccination or infection.

And with better treatments for those who do become ill, one way or another everyone is less at risk to some degree than they were previously.

Hospital cases still rising

But the sheer weight of infections means while Omicron is milder, patient numbers in hospital have been going up.

The total has doubled in just under a fortnight in England to more than 14,000. That, however, is still well under the 34,000 peak last winter when more than a third of beds were occupied by Covid patients. Rises are being seen elsewhere in the UK, although gaps in publishing data over the festive period make it hard to judge how quickly.

But to fully understand what's happening you need to look beyond the headline figures.

Hospital patients appear less sick

A hospital case this winter is not the same as one from earlier in the pandemic.

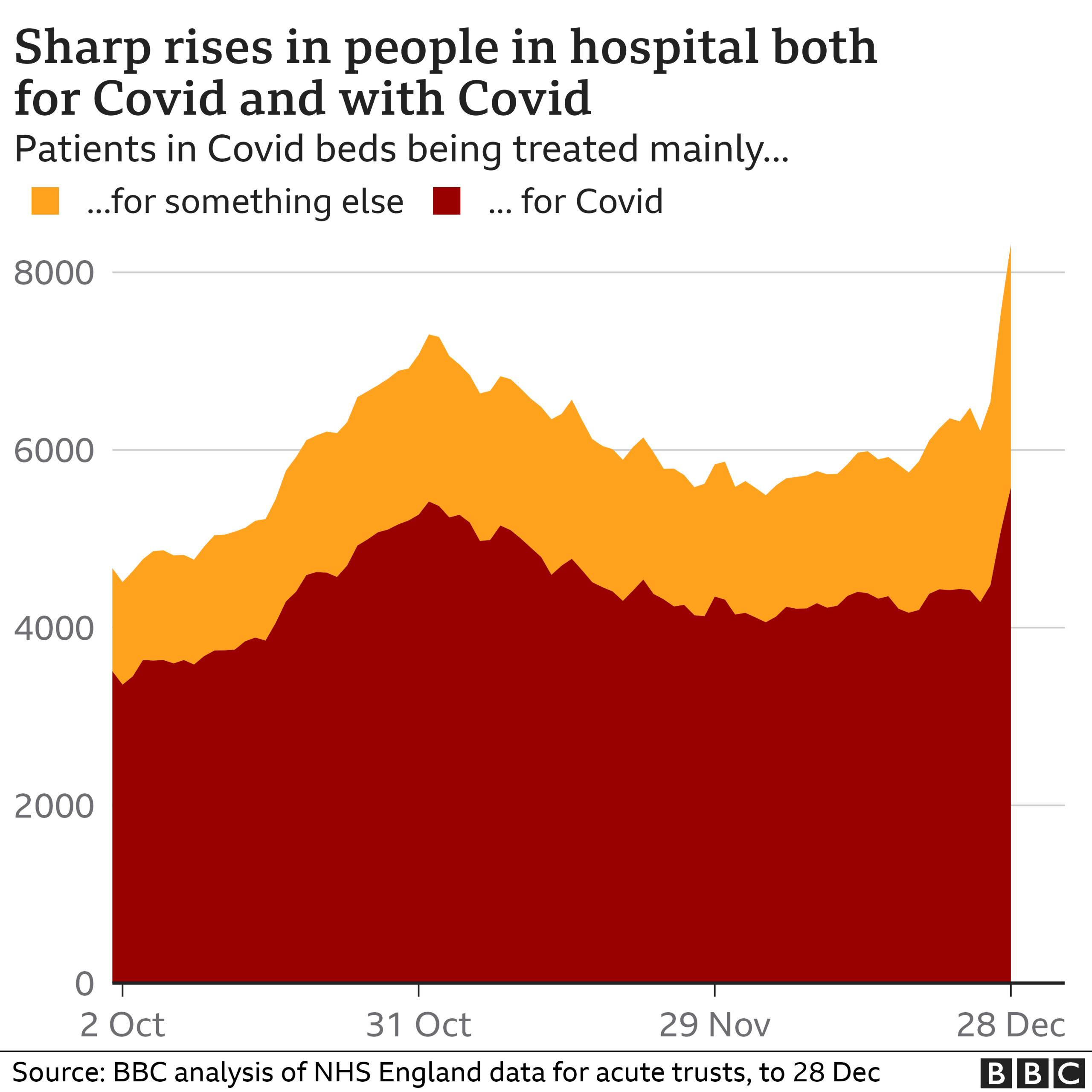

For one thing, a growing proportion of hospital patients with Covid are being treated for something else. They just happen to have the virus.

Latest data, from last week, suggested a third of those admitted to hospital in England were in this position. That's up from a quarter in the autumn. This data is not published in the UK's other nations but there is no reason to think it is any different.

Yet, as the chart above shows, the absolute number in hospital with Covid, and therefore severely ill, is still climbing. And even those who are not in primarily for Covid add pressure to the NHS because of the need for extra infection control measures.

Another sign of how Covid has changed is that the patients who are being treated for it are not getting as sick.

There have been early reports that patients are not spending as long in hospital and the numbers needing critical care has hardly changed. All this puts the NHS in a stronger position to cope.

But make no mistake, the pressures on the front line are severe.

Difficult month facing hospitals

The number of people coming to hospital ill with Covid is well above what the NHS would normally get for all types of respiratory infections combined - and the numbers are rising.

How high they will go is still uncertain. Much depends on whether there will be a big wave of older, frail patients being admitted if Omicron infections move from younger people into older age groups.

There is growing confidence this may not happen though as hospital bosses are reporting even the outbreaks in care homes are not translating into the hospital admissions you would expect. What's more, London as a whole may have already peaked. The boosters, it seems, are holding up.

If you can't see the lookup, click here

But the situation is further complicated by the high number of staff absences driven by large numbers having to isolate.

Again England has the most comprehensive data. Pre-pandemic NHS staff absence in winter was around 5%. The latest data shows it was 8% in the week up to Christmas.

The combined pressures have led at least half a dozen NHS trusts to declare major incidents - when demand exceeds capacity - in the past week.

Should more have been done?

All this begs the question why something more is not being done to suppress the wave in England - Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland all have tougher restrictions in place.

The problem now - illustrated by modelling produced for the government by Warwick University, external - is the window may already have passed. The research suggests even a return to lockdown with only schools open would have virtually no effect on hospitalisations if introduced today.

To have had a significant impact measures would need to have been introduced by Boxing Day or earlier, before Omicron had spread so much.

Even then the argument in favour of tougher action was unclear as infections and hospitalisations would rebound once restrictions were lifted. Largely all it would have achieved is delaying and spreading out illness.

That may have helped the NHS, but would have had to be balanced against wider costs of restrictions to society, the economy and mental health from another lockdown.

What does seem likely is the wave will come and go pretty quickly - even in other parts of the UK the restrictions in place are expected to only have a limited impact.

And once it does, experts believe the extra immunity acquired will mean the population will be even better protected for the future.

Data journalism by Christine Jeavans

Follow Nick on Twitter, external

Read more from Nick

Related topics

- Published5 July 2023

- Published5 July 2022