Fixing the NHS - a near impossible job for new PM?

- Published

Alarm bells are ringing loud and clear in the NHS - what will the new PM do to fix it?

On Monday we will find out who will be the new prime minister. But as summer makes way for autumn, the alarm bells are ringing loud and clear in the NHS.

And while the cost of living crisis has dominated the attention during the leadership contest, talk to anyone in the NHS and they will tell you they are worried what the coming months will bring.

Put simply, this summer has been worse than any winter this century. Dr Adrian Boyle, of the Royal College of Emergency Medicine, says the demise has been so sharp that the service is "struggling to perform even its central function - to deliver care safely and effectively".

It is easy to see why he and others are worried. Wherever you look, the system is on its knees. The waiting list for non-urgent treatment has ballooned, with nearly one in eight people in England currently waiting for care.

And those who are seriously ill are facing dangerously long waits. It is taking three times as long as it should for ambulance crews to reach heart attack and stroke victims.

Meanwhile, those who have suffered a cardiac arrest are waiting more than two minutes longer than they should - every minute's delay reduces the chances of survival by 10%.

But it is not only the ambulance service which is struggling. When patients come to A&E, long waits for a bed are becoming increasingly common, with those of 12 hours at a record level.

Put this all together, experts warn, and patients are at risk. The Association of Ambulance Chief Executives warned that in July alone, nearly 40,000 patients may have come to harm.

Problems years in the making

So what can be done about it? There is no simple solution. The problems being seen have been years in the making - they are not just pandemic-related.

Firstly, the NHS is drastically short of staff - one in 10 posts is currently vacant, the highest it has been since records began five years ago - and this limits the ability of the health service to expand services.

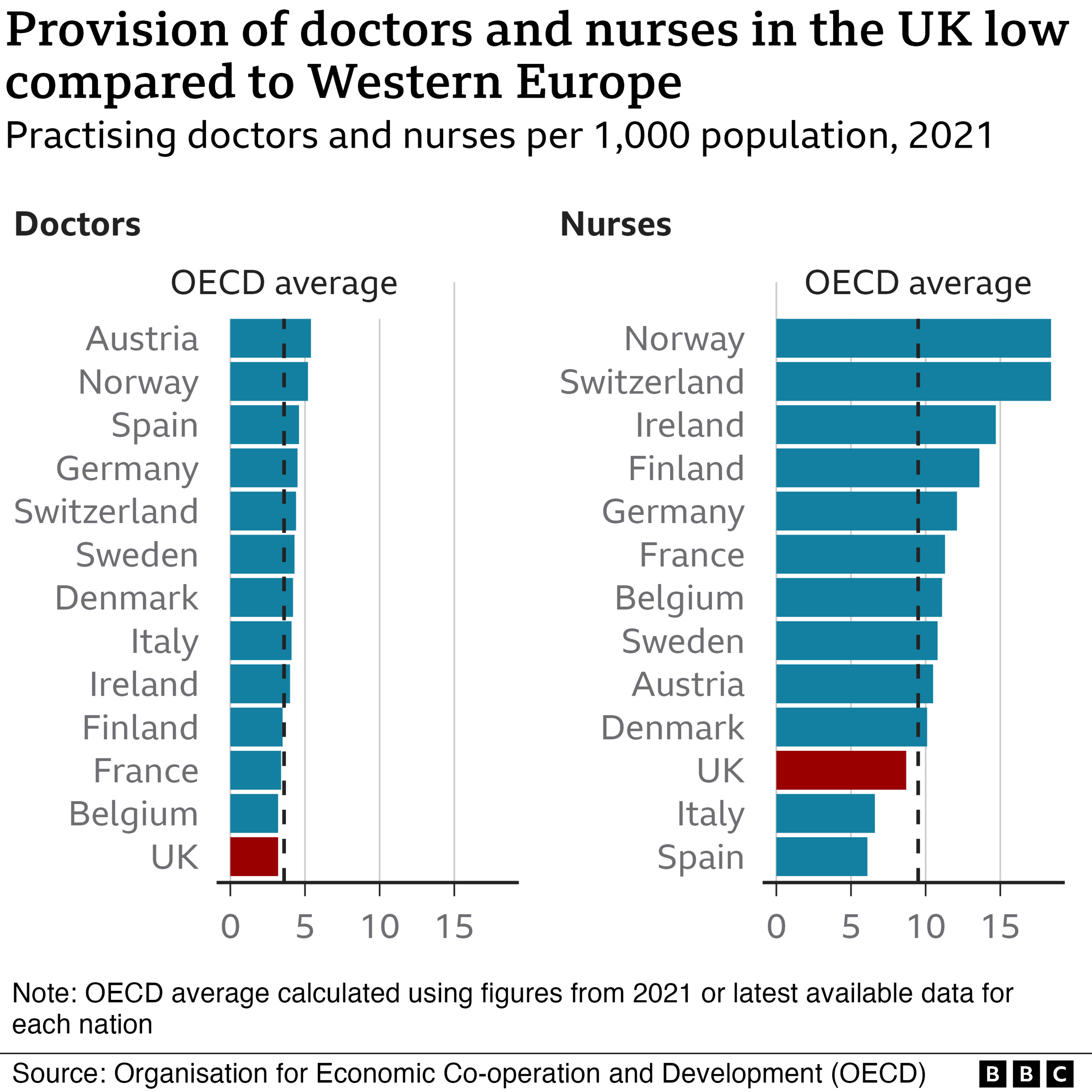

Many countries face shortages, but per head of population the UK has fewer doctors and nurses than many other Western European nations.

It takes time to train more and while the numbers entering training are now increasing, the NHS has certainly been hampered by decisions made in the mid-2010s when bursaries were taken away from nurses and there was limited action by ministers to boost the workforce.

Jeremy Hunt, who was health secretary during that period, is on record as saying it was probably his biggest single mistake of his stewardship of the NHS.

Does the NHS need more money? Many argue it does.

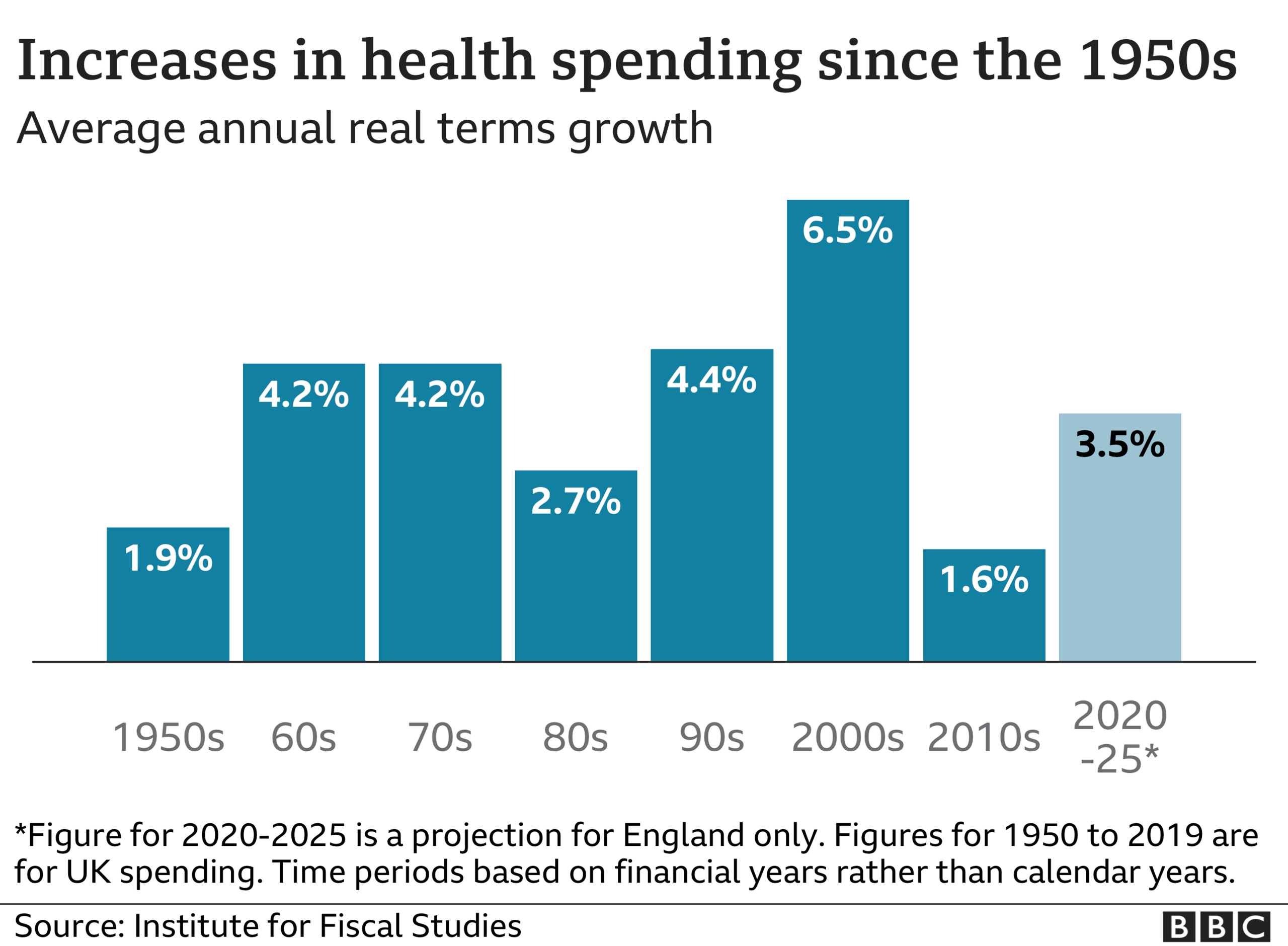

A decade of austerity saw the health service awarded much smaller rises than it has historically received, although the government has gone some way to rectifying that now.

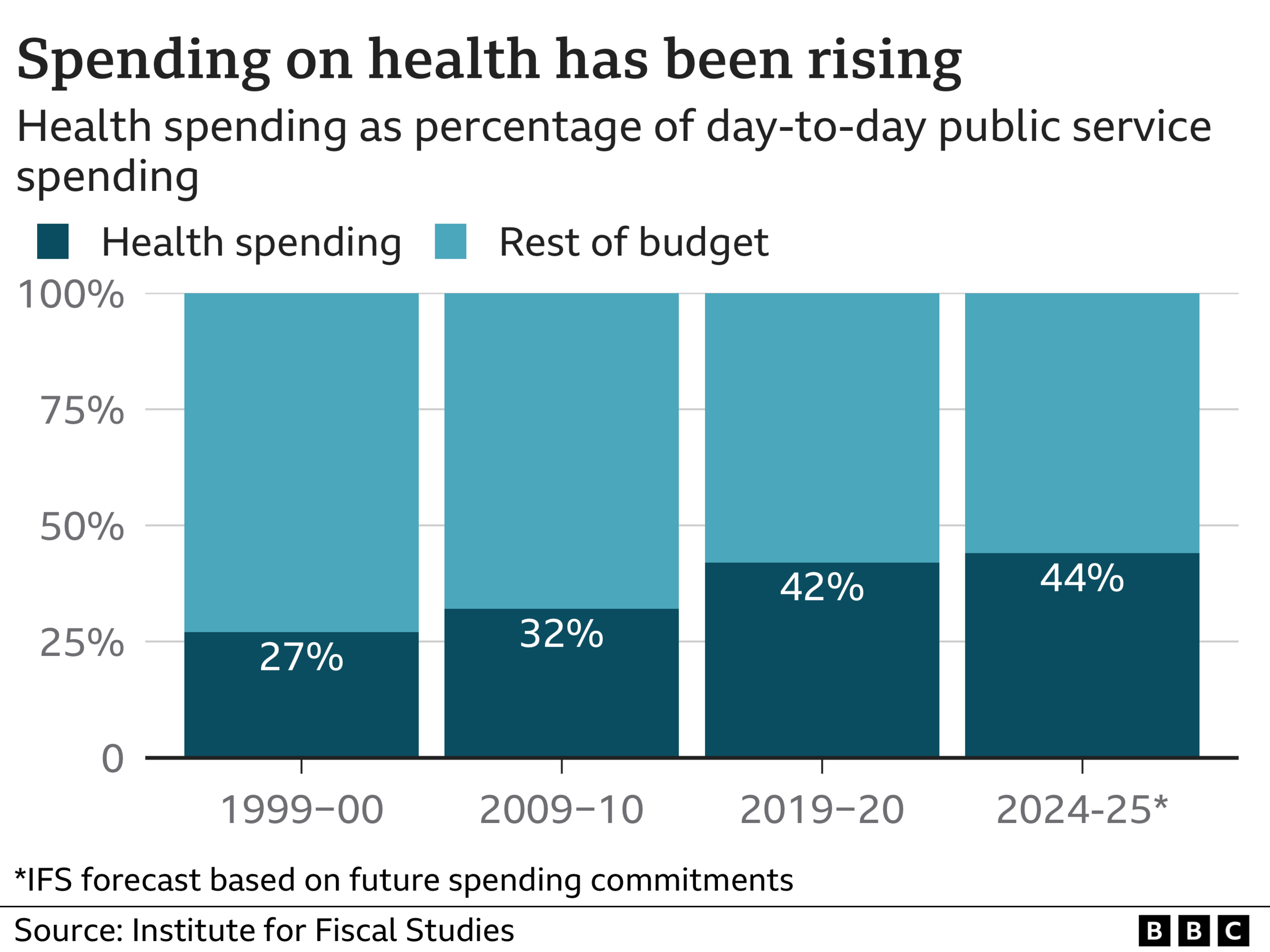

But in thinking about the budget, it is also worth considering just how much of day-to-day public spending is now diverted to the NHS.

At the turn of the century, the health service took just over a quarter. Now it is fast approaching a half.

'It is time to rethink approach to NHS'

There is clearly a limit to how much the budget can keep going up - resources are not infinite. It is a point made in a new book by former British Medical Association president Prof Sir David Haslam, chairman of the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence, the body which decides what treatments should be made available on the NHS.

In the book, Side Effects, in which he recounts his experience of being treated for cancer as well as his thoughts on the health service, he makes the case for continuing with a universal system that means no matter how rich or poor you are, you are entitled to the same treatment.

But he also says the time has come to rethink the NHS's purpose.

He points out that if the budget had been rising as quickly as it did in the 2000s, it would have been consuming close to 100% of gross domestic product by the mid-2070s.

The book goes on to lament the medicalisation of everyday life and our increasing anxiety about our health despite, in general, being healthier than ever.

And Sir David rebukes his fellow doctors for overtreating patients because of a risk-averse culture, which means it is easier to do something for patients than not, even if that means using ineffective medicines.

And, in particular, he is critical of the trend in medical science to pour more and more money into aggressively treating seriously ill patients who are close to death with ever more expensive treatments.

It is time, he says, to work out what the boundaries of the health system should be.

Social care more in need than NHS?

Indeed, some argue that instead of focusing on the NHS, the service may be most helped by increasing the funding given to another service.

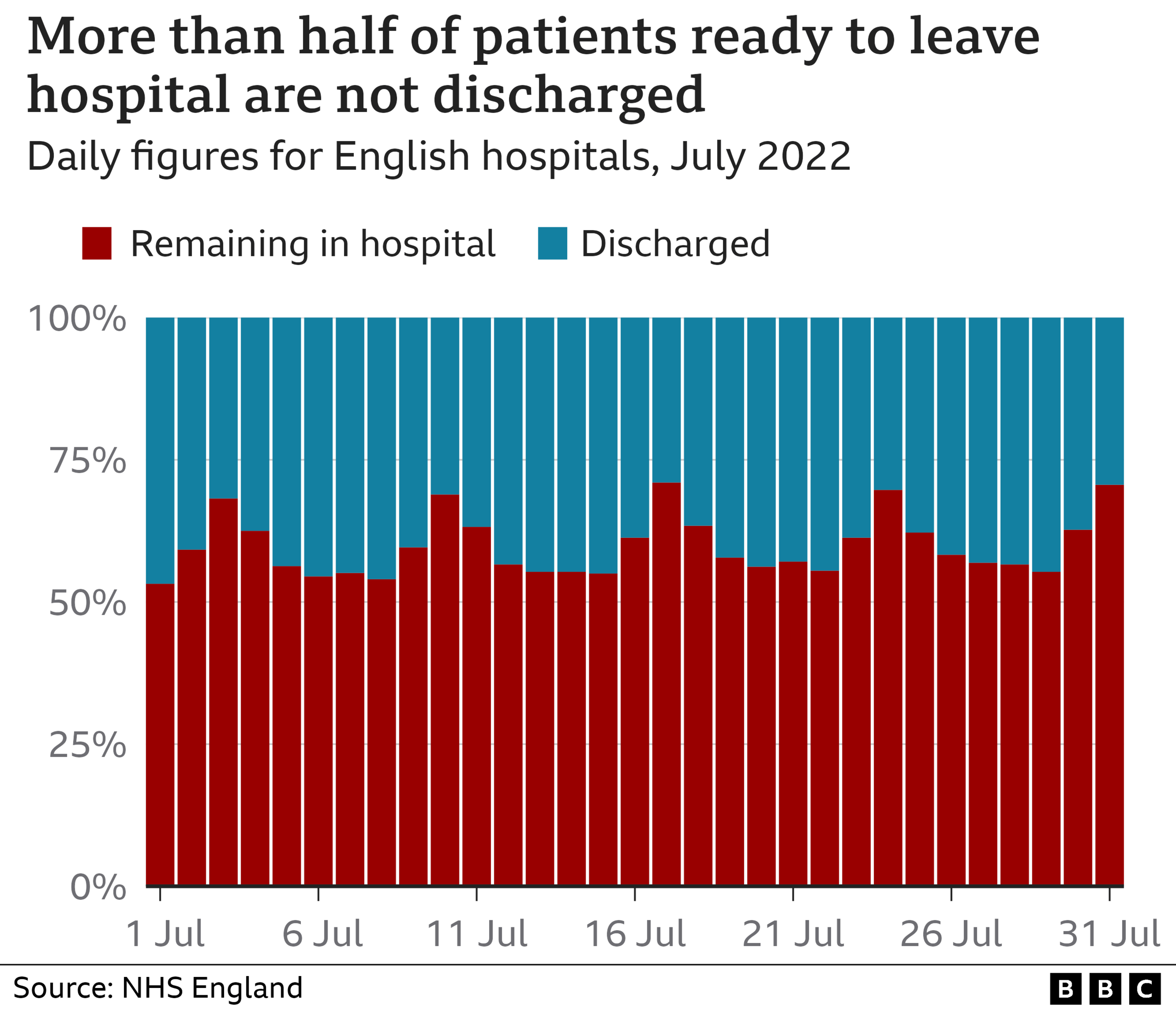

One of the main reasons the emergency system is struggling is that hospitals are struggling to discharge patients who are medically fit to leave, but cannot because there is no support available in the community. Much of that is provided by the social care system which is run by councils.

Data from the early summer shows that more than half of patients ready to leave could not.

Unlike the NHS, social care has not been getting more money over the past decade. Once inflation is taken into account, spending has dropped.

The government is planning to introduce a cap on care costs, but that is about protecting people assets rather than getting more money into the system.

The challenge facing the new PM is huge. And it is not just about the winter, it's about the entire future of the NHS.

Data visualisation by Wesley Stephenson and Liana Bravo

Related topics

- Published5 July 2023

- Published5 July 2022