Heatwave: How hot is too hot for the human body?

- Published

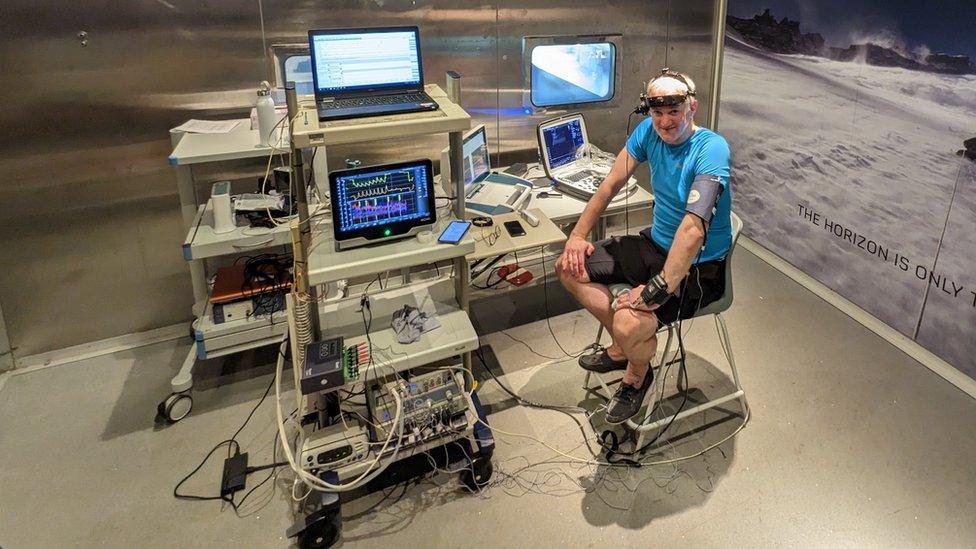

James Gallagher wired up for the heatwave experiment

Sometimes it can feel like the world is on fire.

Europe has been baking in a heatwave nicknamed the settimana infernale - "week of hell" - in Italy. Temperatures above 50C have been recorded in China and the US, where body bags filled with ice are being used to cool hospital patients. The UK has just had its hottest ever June.

And in 2022, the UK recorded a temperature above 40C for the first time. Last year's heatwave has been blamed for 60,000 deaths across Europe, external.

It's no wonder the United Nations has warned we now live in the era of "global boiling".

"I think it's really important to realise it's no longer just something that's distant or far away from us or something in the future. We are really seeing it now," says Prof Lizzie Kendon from the Met Office.

So what does the changing climate mean for our bodies and our health?

I tend to collapse into a sweaty puddle when it gets hot, but I've been invited to take part in a heatwave experiment.

Prof Damian Bailey from the University of South Wales wants to give me a typical heatwave encounter. So we're going to start at 21C, crank up the thermostat to 35C and then finally up to 40.3C - equivalent to the UK's hottest day.

"You will be sweating and your body's physiology is going to change quite considerably," Prof Bailey warns me.

Listen to the Inside Health podcast: How hot is too hot?

Prof Bailey leads me into his environmental chamber. It's a room-sized piece of scientific equipment that can precisely control the temperature, humidity and oxygen levels inside this airtight space.

I've been here once before to explore the effects of cold.

But the shiny steel walls, heavy door and tiny portholes take on new meaning in anticipation of the temperature being cranked up.

I feel like I'm staring out of my oven.

The temperature starts at a perfectly pleasant 21C when the first instruction to "completely strip everything off" comes from Prof Bailey.

In response to a raised eyebrow, I'm reassured we're going to work out how sweaty I get, by seeing how my weight changes.

James getting wired up for the experiment inside the environmental chamber at the University of South Wales.

Next, I'm connected to a dizzying array of gizmos tracking the temperature of my skin and my internal organs, my heart rate and blood pressure. A huge mouthpiece analyses the air I exhale and an ultrasound inspects the flow of blood to my brain through the carotid arteries in my neck.

"Blood pressure is working nicely, heart rate is working nicely, all of the physiological signals at the moment are telling me that you're in spiffing shape," Prof Bailey tells me.

We have one quick brain test to complete - memorising a list of 30 words - and then the fans kick in. The temperature is starting to rise.

My body has one simple goal - to keep the core temperature around my heart, lungs, liver and other organs at about 37C.

"The thermostat in the brain, or hypothalamus, is constantly tasting the temperature, then it sends out all of these signals to try to maintain that," says Prof Bailey.

We take a pause at 35C to take some more measurements. It's warm in here now. It's not uncomfortable - I'm just relaxing in a chair - but I wouldn't want to work or exercise in this.

Prof Bailey is also feeling the heat inside the chamber

Some changes in my body are already clear. I look redder. Damian does too, he's stuck in here with me. That's because the blood vessels near the surface of my skin are opening up to make it easier for my warm blood to lose heat into the air.

Also I'm sweating - not dripping, but positively glistening - and as the sweat evaporates, that cools me down.

We then plough on to 40.3C, and now I feel like the heat is pounding me.

"It's not linear, it's exponential. Five degrees centigrade [more] doesn't sound much, but it really is physiologically so much more of a challenge," Prof Bailey says.

I'm glad we're not going higher. When I wipe my hand across my brow it is sodden. It's time to repeat the tests.

When I chuck my sweaty clothes on the floor, towel off and climb back on the scales I'm shocked to learn I've lost more than a third of a litre's worth of water during the course of the experiment.

The cost of opening up all those blood vessels near my skin to lose heat is also clear. My heart rate has increased significantly and at 40C it is pumping an extra litre of blood per minute around my body than it was at 21C.

This extra strain on the heart is why there is an increase in deaths from heart attacks and strokes, external when temperatures soar.

And as the blood heads to my skin, it's my brain that loses out. Blood flow goes down and so does my short-term memory.

But my body's main goal - keeping my core temperature at around 37C - has been achieved.

"Your body is working really quite nicely to try to defend that core temperature, but of course, the numbers are suggesting you weren't the same beast at 40 degrees as you were at 21 and that's in less than an hour," says Prof Bailey.

The humidity factor

In my experiment only the temperature was changed, but the other crucial factor to consider is the amount of water vapour in the air - the humidity.

If you've ever been really uncomfortable on a muggy night then you can blame the humidity as it impairs our body's ability to cool down.

Sweating alone isn't enough - it's only when the sweat evaporates into the air that it gives us that cooling effect.

When there are high levels of water already in the air, it's harder for sweat to evaporate.

Damian kept the humidity fixed at 50% (not unusual for the UK), but a team at Pennsylvania State University in the US tested a bunch of healthy young adults at different combinations of temperature and humidity. They were looking for the moment when core body temperature started to rise rapidly.

"That's when it becomes dangerous. Our core temperature starts to rise and that can lead to organ failure," says researcher Rachel Cottle.

And that danger point is reached at lower temperatures when the humidity is high.

The concern is that heatwaves are not only becoming more frequent, longer in duration and more severe, but they're becoming more humid too, says Cottle.

She points out that last year, India and Pakistan were hit by a severe heatwave with both critical temperatures and high humidity. "It's definitely a 'now' problem, not a future problem," she says.

The human body is built to operate at a core temperature of about 37C degrees. We become more light-headed and prone to fainting as the core rises closer to 40C.

High core temperatures damage our body's tissues, such as heart muscle and the brain. Eventually this becomes deadly.

"Once the core temperature rises to around about 41-42 degrees centigrade we start to see really, really significant problems and if not treated the individual will actually die as a result, succumbing to hyperthermia," says Prof Bailey.

This phenomenon - heat stroke - is a medical emergency.

People's ability to cope with the heat varies, but age and ill health can make us far more vulnerable, and temperatures we may have once enjoyed on holidays may be dangerous at a different stage in life.

"You're going to leave the lab today with a smile on your face - all of these statistics coming are telling me that you have risen to the challenge and you've done a jolly good job," says Prof Bailey

But old age, heart disease, lung disease, dementia and some medications mean the body is already working harder to keep going, and is less able to respond to the heat.

"Every day it's a physiological challenge for them, now when you throw in extra spicy heat and humidity, sometimes they can't rise to that challenge," says Prof Bailey.

How to cope?

Many of the tips for coping with the heat are obvious and well known - stay in the shade, wear loose fitting clothes, avoid alcohol, keep your house cool, don't exercise in the hottest parts of the day and stay hydrated (you saw how much I sweated in an hour).

"Another tip is try not to get sunburned. A mild sunburn can knock out the ability to thermoregulate or to sweat for as long as two weeks," says Prof Bailey.

But dealing with the heat is something we could all have to become used to dealing with.

Without action on climate change Prof Lizzie Kendon said the hottest UK summer day could increase by 6C under a high-emission scenario: "That's a huge increase by the end of the century."

Follow James Gallagher on Twitter, external.

Inside Health was produced by Gerry Holt and Dan Welsh.

Related topics

- Published13 July 2023