Scientists crack mystery of how MS gene spread

- Published

Why are diseases more common in some parts of Europe than others, and why are northern Europeans taller than their southern counterparts?

An international team of scientists say they have unearthed the answer in the DNA of ancient teeth and bones.

The genes which protected our ancestors from animal diseases now raise the risk of multiple sclerosis (MS).

The researchers call their discovery "a quantum leap" in understanding the evolution of the disease.

And they say it could change opinions on what causes MS, and have an impact on the way it is treated.

Why look at MS?

There are about twice as many cases of multiple sclerosis per 100,000 people in north-western Europe, including the UK and Scandinavia, compared with southern Europe.

Researchers from the universities of Cambridge, Copenhagen and Oxford spent more than 10 years delving into archaeology to investigate why.

MS is a disease where the body's own immune cells attack the brain and spinal cord, leading to symptoms like muscle stiffness and problems walking and talking.

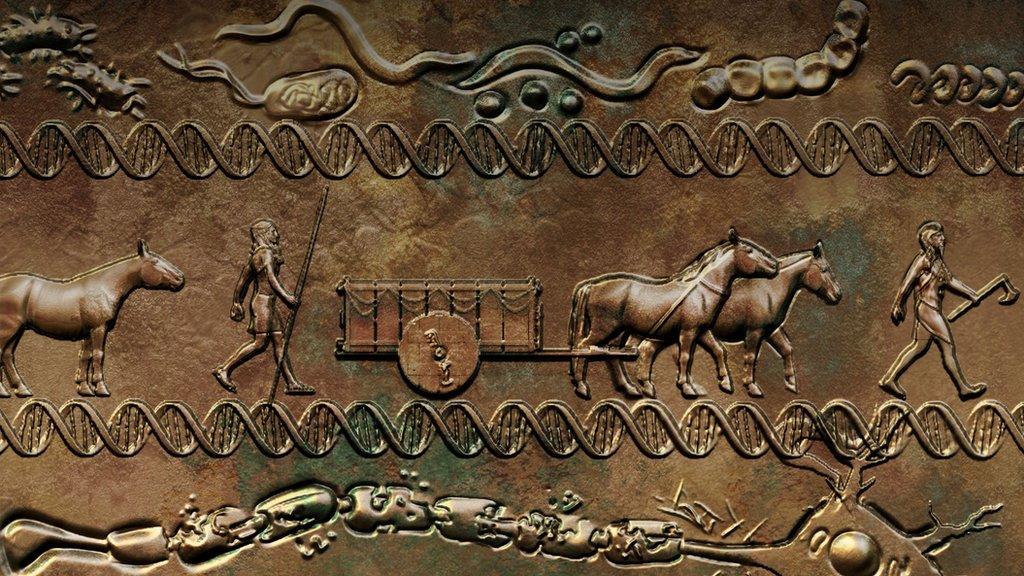

They discovered that genes which increase the risk of MS entered into north-western Europe about 5,000 years ago via a massive migration of cattle herders called Yamnaya.

Our ancestors lived alongside animals, such as cattle and horses

The Yamnaya came from western Russia, Ukraine and Kazhakstan, and moved west into Europe, says one of four Nature journal papers published, external on the topic.

The findings "astounded us all", said Dr William Barrie, paper author and expert in computational analysis of ancient DNA at University of Cambridge.

At the time, the gene variants carried by the herding people were an advantage, helping to protect them against diseases in their sheep and cattle.

Nowadays, however, with modern lifestyles, diets and better hygiene, these gene variants have taken on a different role.

In the present day, these same traits mean a higher risk of developing certain diseases, such as MS.

The research project was a huge undertaking - genetic information was extracted from ancient human remains found in Europe and Western Asia, and compared with the genes of hundreds of thousands of people living in the UK today.

In the process, a bank of DNA from 5,000 ancient humans,, external kept in museum collections across many countries, has now been set up to help future research.

'Find sweet spot'

Prof Lars Fugger, paper author and MS doctor at the John Radcliffe Hospital in Oxford, says the discovery helps "demystify" the disease.

"MS is not caused by mutations - it's driven by normal genes to protect us against pathogens," he explains.

Vaccinations, antibiotics and higher standards of hygiene have changed the disease landscape completely - many diseases have disappeared and people are living decades longer.

The researchers say modern immune systems may now be more susceptible to autoimmune diseases, like MS, where the immune system attacks the body rather than protecting it.

Drugs currently used to treat MS target the body's immune system, but the downside is the risk of suppressing it so much that patients struggle to fight off infections.

When treating it, we are up against evolutionary forces, Prof Fugger says.

"We need to find the sweet spot where there is a balance with the immune system, rather than wiping it out."

The skull of a neolithic man found in Porsmose, Denmark, in 1947

The team now plans to look for other diseases and conditions in ancient DNA, and follow them back in time.

Their research could reveal more about the origins of autism, ADHD, bipolar disorder and depression.

Another Nature paper, external uncovered even more clues about our genetic past - that the Yamnaya herders could also be responsible for north-western Europeans being taller than southern Europeans.

And while northern Europeans carry more genetic risk for MS, southern Europeans are more likely to develop bipolar disorder, and eastern Europeans more likely to have Alzheimer's disease and type 2 diabetes.

DNA from pre-historic hunter-gatherer people raises the risk of Alzheimer's, but ancient farmers' genes are linked to mood disorders, the research explains.

It also discovered that humans' ability to digest milk and other dairy products and survive on a vegetable-heavy diet only emerged about 6,000 years ago. Before that, they were meat-eaters.

The research compared DNA from thousands of ancient skeletons found in Eurasia to genetic samples from current-day Europeans.

- Published19 December 2023

- Published4 April 2023

- Published27 November 2019

- Published14 April 2022

- Published20 October 2022

- Published26 May 2022