Pioneering gene therapy restores UK girl's hearing

- Published

Opal playing at home

A UK girl born deaf can now hear unaided, after a groundbreaking gene-therapy treatment.

Opal Sandy was treated shortly before her first birthday - and six months on, can hear sounds as soft as a whisper and is starting to talk, saying words such as "Mama", "Dada" and "uh-oh".

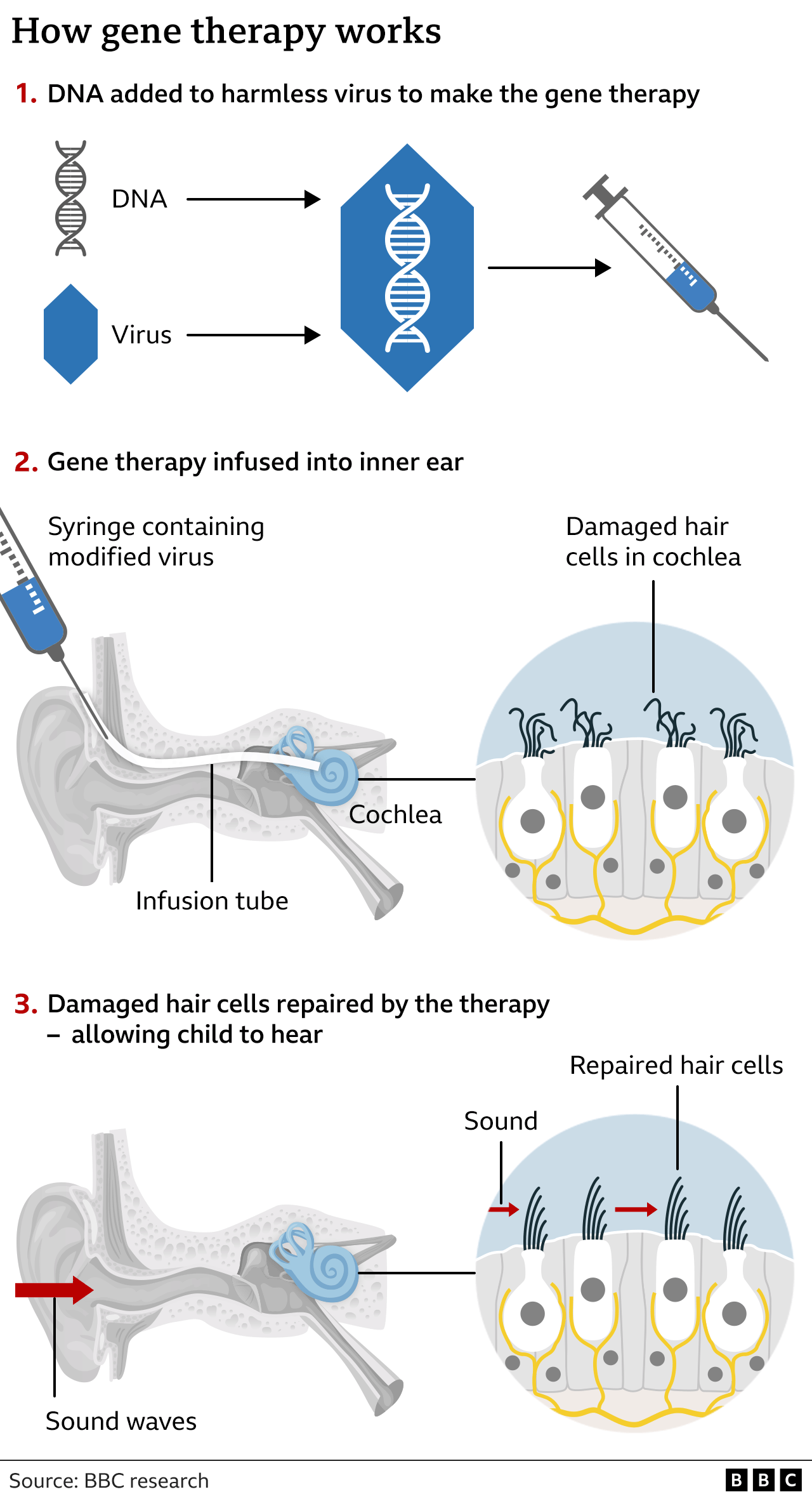

Given as an infusion into the ear, the therapy replaces faulty DNA causing her type of inherited deafness.

Opal is part of a trial recruiting patients in the UK, US and Spain.

Doctors in other countries, including China, external, are also exploring very similar treatments for the Otof gene mutation Opal has.

Her parents, Jo and James, from Oxfordshire, say the results have been mind-blowing - but allowing Opal to be the first to test this treatment, made by Regeneron, was extremely tough.

"It was really scary, but I think we'd been given this unique opportunity," Jo told me in an exclusive TV interview for BBC Breakfast News.

Her sister, Nora, five, has the same type of deafness and manages well wearing an electrical cochlear implant.

Rather than making sound louder, like a hearing aid, it gives the "sensation" of hearing, by directly stimulating the auditory nerve that communicates with the brain, bypassing the damaged sound-sensing hair cells in a part of the inner ear known as the cochlea.

In contrast, the therapy uses a modified, harmless virus to deliver a working copy of the Otof gene into these cells.

Opal had the therapy in her right ear, under general anaesthetic, and a cochlear implant put into her left.

Just a few weeks later, she could hear loud sounds, such as clapping, in her right ear.

And after six months, her doctors, at Addenbrooke's Hospital, in Cambridge, confirmed that ear had almost normal hearing for soft sounds - even very quiet whispers.

Without a working OTOF gene, the hair cells, although functioning, cannot send signals to the nerve (shown in yellow in this diagram)

"It's wonderful seeing her respond to sound," chief investigator and ear surgeon Prof Manohar Bance told BBC News.

"It's a very joyful time."

Experts hope the therapy could also work for other types of profound hearing loss.

More than half of hearing-loss cases in children have a genetic cause.

And Prof Bance hopes the trial can lead to gene therapy being used for more common types of hearing loss.

"What I am hoping is that we can start to use gene therapy in young children... where we actually restore the hearing and they don't have to have cochlear implants and other technologies that have to be replaced," he said.

Opal shortly after her procedure

Hearing loss caused by a variation in the Otof gene is not commonly detected until children are two or three years old, when a delay in speech is likely.

But genetic testing for at risk families is available on the NHS.

Prof Bance said: "The younger we can restore hearing, the better for all children because the brain starts to shut down its plasticity [adaptability] after the age of about three or so."

Opal's experience, alongside other scientific data from the trial, is being presented at the American Society of Gene and Cell Therapy in Baltimore, in the US.

Martin McLean, from the National Deaf Children's Society, said more options were to be welcomed.

"With the right support from the start, deafness should never be a barrier to happiness or fulfilment," he said.

"As a charity, we support families to make informed choices about medical technologies, so that they can give their deaf child the best possible start in life."

Additional reporting by Nicki Stiastny and James Anderson.

- Published7 February 2017

- Published6 February 2024

- Published27 April 2024

- Published9 February 2023