Inside Sarajevo: A photographer's tale

- Published

- comments

The former Bosnian Serb military commander Ratko Mladic is now in UN custody in the Netherlands awaiting trial on genocide charges.

He is accused of atrocities committed during the Bosnian conflict in the 1990s, including the massacre of an estimated 8,000 Muslims at Srebrenica, and was on the run for 16 years.

Looking back on the conflict, I remember watching the wire photographs slowly drip into the system and the pictures on the Nine O'Clock News of street fighting and the struggle by civilians to escape the growing crisis. For those based in Europe, the conflict in former Yugoslavia was accessible and drew many photographers, both seasoned professionals and many who at that time had little experience of reporting from a conflict zone.

Anja Niedringhaus was one of those whose first experience of war photography came in the Balkans. Since then she has covered every major conflict including the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, while working for a number of news organisations such as the European Press Photo Agency (EPA).

Today she is a staff photographer for the Associated Press (AP) and has received numerous awards for her work, including the Courage in Journalism Award from the International Women's Media Foundation

Anja's time in the Balkans began covering the declarations of independence from Yugoslavia by Slovenia and Croatia in 1991. A year later she arrived in Sarajevo and the region would be her home until 1995, though she was back in 1998 when the war in Kosovo broke out.

I asked Anja to outline how she came to be in Bosnia during that time:

"My career in journalism began as a freelancer. I had just finished university where I studied literature, philosophy and journalism and in 1990 I got my first staff job with EPA and was based in Frankfurt, Germany.

"I was never supposed to cover the war in Yugoslavia. My editor thought I was too young and a woman with no experience covering conflicts. It didn't seem possible. I had covered the fall of the Berlin Wall and a couple of other assignments, including trips with the Pope, but never a conflict.

"Still I refused to give up because I believed the job of a real journalist would be to cover a war like this in the middle of Europe. I wrote a long letter to my boss telling him why I had to go and why he needed to send me. I don't remember the words I wrote but whatever they were, they convinced him. One week later, I was on the road.

"My first trip was a couple of weeks. I was young and inexperienced but I met colleagues who helped me and guided me through my first weeks. I will never forget them and the advice they gave me helps me even today. I returned at the end of the assignment but I knew I had to go back. Just two weeks later I returned to Yugoslavia.

"I stayed in the region until 2001. I moved first to Zagreb and lived there but soon I moved to Sarajevo where I stayed until the siege ended. Even today, I still have a suitcase there. Every once in a while, I get a phone call from my friends in Sarajevo telling me to come back and pick it up."

The siege of Sarajevo is something that many will remember watching on the nightly news broadcasts; what was it like to be inside the city?

"Sarajevo was home for me for many years. Friendships I made then have been lasting.

"Living in a city under siege brought us together and we shared everything with each other. If one had pasta or fresh fruit, she shared it with the other. I remember one night I got a message on my walkie-talkie from an AP colleague who had got hold of some pasta. I was told to make my way to their office to share it with them, but to get there I had to go through sniper alley.

"That part of Sarajevo was constantly under attack. Snipers chased people as we moved through the streets like rabbits. That pasta evening, the sniping was relentless. I jumped into my car with another colleague and we tried to shield the front window with our bulletproof vests. We screamed out of the garage at full speed. I was hiding so far down in the car while still trying to drive I could hardly see the street in front of me. I drove so fast we got to the pasta party without a single bullet in the car. I remember that night like it was yesterday.

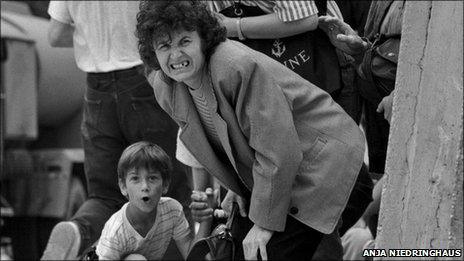

A woman and her son take cover behind a concrete wall erected to protect them from incoming sniper fire

"What was also unique for Sarajevo was the camaraderie. No matter who was working for whom, we never let competition put anyone in danger or stand in the way of our co-operation. Even today when I meet my colleagues from those days, it is as if it were yesterday. Time slips away. I felt in that war in Sarajevo the sense of the community of journalists as a family. It was so unique and in the 20 years since then, I have never found it again."

I had heard you were badly wounded whilst there; can you share the details?

"In my first week in Croatia, I was hit by a sniper but the bullet grazed my flak jacket.

Anja Niedringhaus now works for AP and has recently been covering the conflict in Libya

"Later I was intentionally run over by a Serbian police officer while I was covering the anti-Milosevic demonstrations in the centre of the city. Thousands of people from all over the country marched that night toward Belgrade and I was hit by the police car.

"My jacket got caught in the bumper and the policeman who was driving saw I was caught but wouldn't stop. The car ran over my legs, breaking them in several places. I passed out but the Serbian people helped me and took me to a hospital. But as they were afraid they would be picked up by police, they just left me there on the floor.

"Colleagues who were searching for me found me hours later and convinced the doctors to help me. They eventually put a cast on my legs but in the meantime, the police had got hold of my passport and wouldn't give it back to me. They insisted I stay, claiming I had committed a criminal act by taking part in the demonstration.

"Finally my colleagues convinced them I did nothing wrong and after taking 100 Deutsche Mark, the police let me go. I went back to Germany and needed three operations. But still, three months later, I was back in Albania covering an uprising."

What were the logistics like working in a war zone at that time?

"The way we worked in those days was very different from today. I was working with film, dragging in suitcases of chemicals to develop and always worrying about when my supplies would run out and fearing I wouldn't be able to develop my films.

"I think I knew every good bathroom in hotels all over Europe because it was in these small spaces I could make a functional darkroom in minutes. At the time, we worked with Hasselblad scanners, called the Dixel, and pictures were transmitted in black and white.

"It was time-consuming and laborious. Toward the end, we filed in colour but only on request because the satellite costs were enormous as we used analogue modems.

"I always had a good pocketknife and a small screwdriver on me to connect the modem with the phone line.

"One day in Albania, I destroyed the hotel's phone communications as I was trying very hard to transmit my picture. The modem was trying to catch a signal but in the end it caught fire and took the entire hotel phone communication system down. When I checked out of the hotel, they charged me three nights plus $700 (£427) to fix the phone lines.

"In those days our satellite phones were the size of fridges. Today our equipment is sophisticated and compact. We use digital cameras and our transmission equipment is the size of a laptop.

"No longer do we have to go back to an office or a hotel room. We file on the spot. The immediacy of the internet and the rush to get our images on line means rapid filing today.

"In Libya earlier this year, I was transmitting from the front line within minutes of taking a photo. As I was filing, the front line would move. The place I thought was safe suddenly turned into chaos with shells smashing down around me. So I grabbed my equipment and ran, carrying cameras, laptop and satellite phone, looking for the next place to transmit.

Lastly, can you offer an insight into your motivation to continue to cover conflicts?

"It's difficult to answer the question of my motivation to keep covering conflicts. Maybe it is because I learned early in my career about how to cover conflict, I am not sure. But when I decided to go to Yugoslavia to cover that war on Europe's doorstep, I had the feeling that there is nothing more important in life to cover. I think for me to be a true journalist means to cover conflicts because sadly, in the last 20 years, there has not been a single year that I have not seen a conflict.

"But the world is not only about wars and conflict. Life has to have balance as does my work. I try very hard to keep that balance in my work. I cover also sports and political events and papal trips.

"That balance keeps me sane and reminds me that I should never take war as normal. So even today after witnessing so much war, I still arrive at a conflict filled with wonder at how this can happen and feel for the people and the soldiers caught up in the conflict. I see how their lives have been turned upside down by war.

"The day I enter a war zone and think it is normal is the day I will stop covering wars."