Adapt to survive: A photographer's view of the market today

- Published

- comments

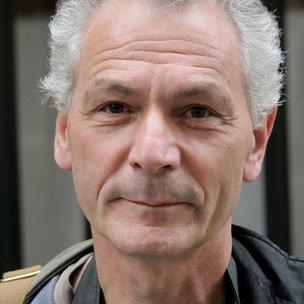

Philip Wolmuth has worked as a freelance photographer for 30 years

In the second of a week-long series by guest bloggers freelance photographer Philip Wolmuth looks at the current market for freelance photographers, and despite all the gloom, sees some hope for the future.

Frank Zappa once said: "Jazz isn't dead - it just smells funny". At the end of 2011 photojournalism is in a similar condition.

In November the picture editor of Community Care called to let me know that the issue that had just gone to press would be the last - future editions will appear online only. The award-winning weekly for care professionals was the fifth of my long-standing magazine clients to close this year. Print is dying, slowly strangled by the move to the web of both advertisers and readers - and publishers are struggling to make the web pay.

Earlier the same month Getty Images, external, one of the two largest photo agencies in the world (by revenue), announced a cut in payments to its editorial contributors. Photographers supplying the private equity-owned company saw their share of reproduction fees reduced from 50% to 35%.

It is widely assumed that the move was made to enable Getty to maintain profit margins while pursuing an aggressive price-cutting strategy. Pictures that sold for £70 or £100 five or six years ago, now habitually go for £15 or £20. Even 50% of £15 is not very much.

Over the same period, one regular contributor to Alamy, external I know has seen her annual sales remain roughly steady, but her income fall from £42,000 to £18,000 - a drop in average sale price of almost 60%. Alamy describes itself as "the world's first open, unedited collection of images". It has more than 25 million of them on its servers, and thousands of contributors, including many - amateurs, students and others - who would never have had access to the market in the pre-digital era.

A homeless woman helps a man in need of medical attention into the Crisis Christmas shelter in Bermondsey, South London, 1997

To the agencies it makes little difference whether they sell one picture for £100, or five for £20, but such low fees (and some are even lower) are not sustainable for photographers. The strategy is only possible because many of the smaller agencies, an integral part of the photo market in the days of film, were either bought up by the big players, or folded - unable to handle the very considerable costs of digitisation.

The resulting concentration of ownership, together with the proliferation of imagery from a much wider range of sources, has done serious damage to an income stream that has been a mainstay for many freelancers ever since Robert Capa, Henri Cartier-Bresson, George Roger and David Seymour set up Magnum in 1947, external.

So with magazines closing, newspapers cutting back to compensate for declining revenues, and income from stock disappearing down the plug hole, things don't look promising. And I haven't even mentioned the global economic crisis. It seems that the business model that has sustained photojournalism for more than 60 years is on its last legs.

Working through the night at Edgware Road tube station on the Bakerloo Line, 2010

But photojournalism has never been easy, despite laments in various quarters for a lost age of plenty. Certainly there was a time when a small elite of high profile photographers travelled the globe, expenses paid and publication guaranteed. An elite still exists, although now very much smaller, but everyone else, myself included, has always had to scrabble around, picking up a patchwork of non-governmental organization (NGO) commissions to pay for a foreign trip, or mixing more commercial assignments with self-financed personal work sold after completion, either as a whole story or as single pictures.

Reasons to be cheerful? Images are everywhere. The technology that has brought us the gargantuan agencies, each with many millions of ever-cheaper images accessible at the touch of a button, has also brought us an astonishing array of new outlets for still and moving images. Some of them - this blog, for instance - even pay!

We are in a period of transition. Although too much web content generates no income for its creators, new revenue streams are gradually establishing themselves. Some sites already bring in real money from advertising, or paywall subscriptions. News websites are beginning to commission or buy in photo stories in the form of multimedia pieces (still images and sound), or web documentaries (video, stills and sound, sometimes with interactive features). Some of the bigger NGOs are doing the same.

I've found the last couple of years the most difficult since I started out - but not fatal. Can the new opportunities replace the fading print market and collapsing library sales? Probably not for everyone. However, many of the old rules still apply. Quality and originality still have value. Niche specialisms are always in demand. Surviving as a freelance in the digital age requires new skills and an openness to new markets, but it is possible - and at least the scrabbling around should feel familiar. One other thing jazz and photojournalism have in common: if you want to get rich quick, try banking.

Racegoers approach the Royal Enclosure at Ascot racecourse on Ladies Day, 2009

Philip Wolmuth has worked as a freelance photographer for 30 years, with a primary interest in documenting the impact of social, economic and political forces on individuals and communities. His pictures have appeared widely in newspapers, magazines, trade union journals, books, and public and voluntary sector publications.

He distributes his work through the Reportdigital, external social issues photo library, and his own archive at www.philipwolmuth.com, external.

Tomorrow AP photographer Matt Dunham looks back on his best shots of 2011.

Related posts: