End of deep coal mining

- Published

Kellingley Colliery, in North Yorkshire, closes on 18 December, bringing to an end centuries of deep coal mining in Britain.

Photographers Andrea Baldo and Rita Alvarez Tudela went along to meet some of the miners during their Christmas gathering at the Broken Bridge pub, in Pontefract, to find out how they felt about the closing of the mine and their final shifts.

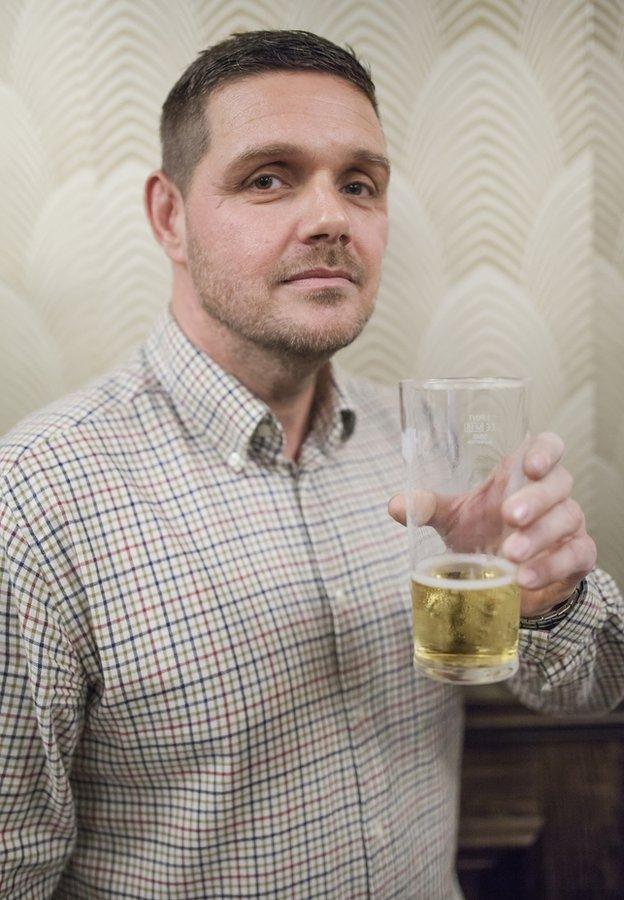

Andrew Rowe Selby, 25 years at the colliery

I feel ridiculous about the closing of the mine. It's hard to explain. I've worked here with this whole group for about 25 years. I put a lot of pressure to stop it closing.

It's hard to find another job. It's like starting all over again, like going back to school. I am thinking about lorry driving next. My father was a miner for 39 years. He now works at the National Coal Mining Museum for England, in Wakefield, West Yorkshire, as a tour guide.

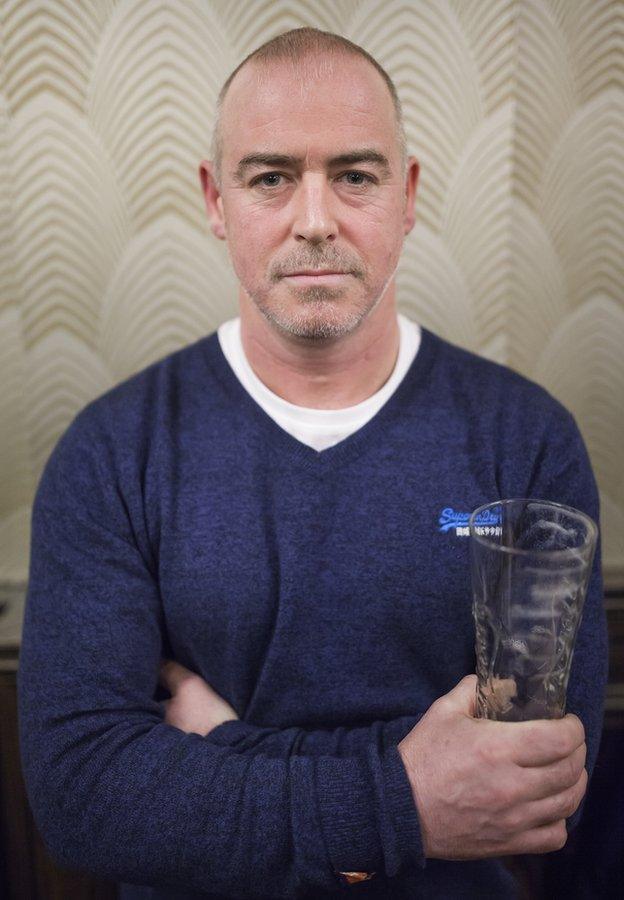

Russell Davis, 33 years at the mine

I feel terrible about the closing of the mine. Because I am 50, I can get a pension. It's been easier for them to shut us because they know that most of us are 50 or older. It's bad for the young because they will need a full-time job, otherwise they lose their houses and everything.

Gavin Williams, 28 years at the mine

I am really unhappy. I thought I'd got a job for my whole life.

For years, coal and gas paid the tax for nuclear energy. Why can't we do something like that to keep it? I think we should keep a diverse energy portfolio. Instead of going for nuclear and solar energy and wind power, which is never going to be the same.

This last week is going to be hard, really hard. To see all my friends, my work colleagues and the industry I know go.

I honestly don't know what follows next.

Stewart Loynes, 11 years at the mine

Basically I think the closing of the mine is government orchestrated, England is an island built on coal and there's millions and millions of tonnes of it in the ground which can quite easily be accessed. You see many power stations within 20 miles of here, but we're getting coal from Colombia cheaper. We also talk about carbon footprint here, but how much does it cost to get it from Colombia?

I've not yet started looking for another job. I'll stay with my children and my family this Christmas, and then I will start looking.

Garry Owen, 38 years at the mine

I feel devastated. It is a sad day to see the end of the industry.

It's such a close community. The miners are going to figure out how to fit elsewhere. If the government had taken the carbon tax off, that could have helped us I think, but they won't do it.

Chris MConnachie, 35 years at the mine

I think the closing is a part of the social history of Britain that is going to be gone now. There is not going to be another industry like this ever again. It is quite an emotional break for people here because it is more of a brotherhood than a job.

I told my grandson that people have respect for coal miners. It is a respectful job. It is a honourable job. I am going to miss it, not the job itself but the people I worked with.

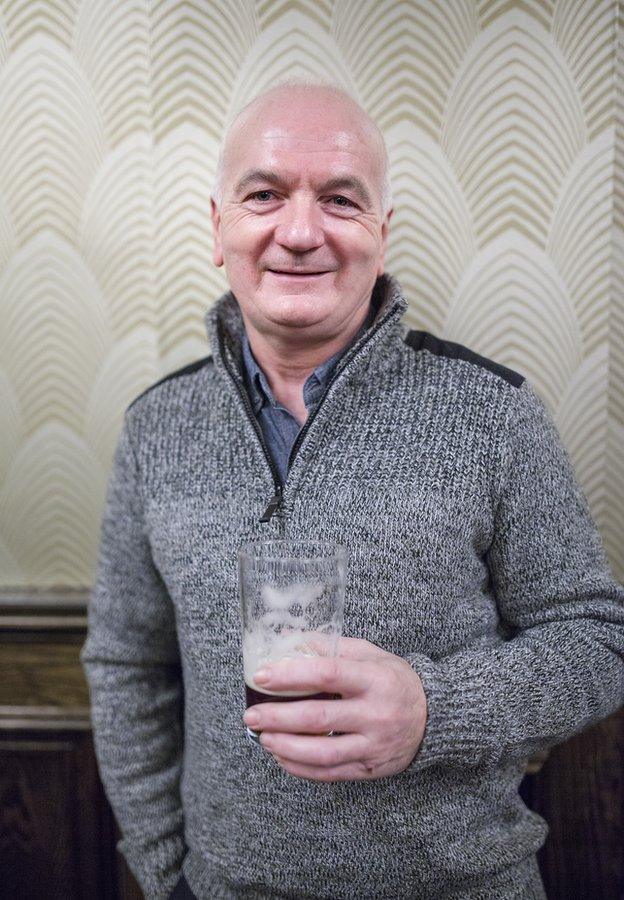

Chris Brougton, 40 years at the mine

I feel very sad for the younger ones. Personally, it's the right age for me to be finishing.

I travelled thousands of miles, where I live is like 20 miles from the pit. I travelled that everyday for the past 40 years to work amongst good friends. It's a community. It is like a family.

I am still at the mine. I will be there for the last shifts. They are going to be sad. We all live in a wide area, and it will be difficult to see each other again.

Photographs by Andrea Baldo with interviews by Rita Alvarez Tudela.

- Published10 December 2015