The 150-year-old story of Sri Lankan tea-making

- Published

Almost 5% of the population of Sri Lanka work in the billion-dollar tea industry, picking leaves on the mountain slopes and processing the tea in plantation factories.

The cultivation and selling of black tea has shaped the lives of generations of Sri Lankans since 1867.

Documentary photographer Schmoo Theune visited plantations in the country to explore the world of Ceylon tea production.

Tea bushes on mountain slopes are situated above the barracks-style housing which each plantation provides for its workers.

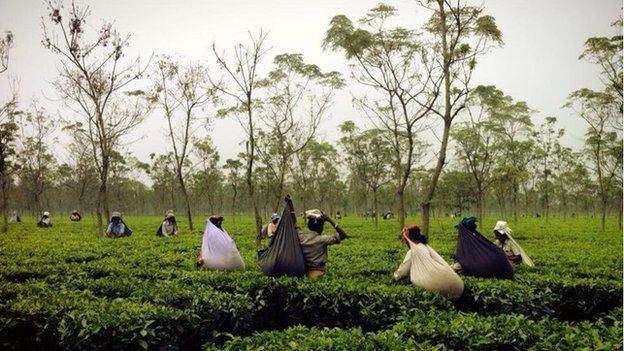

Tea buds must be picked by hand every seven to 14 days, before the leaves grow too tough.

This means the working location can change from day to day, depending on where the buds need to be collected.

The tea leaves are gathered in tarpaulin bags, which are lighter than the traditional wicker baskets that were once used.

The leaves are weighed throughout the day and a tea-picker earns 600 Sri Lankan Rupees (LKR), which is approximately £2.70, if they reach the desired quota of 18kg a day.

If they do not meet this target then they are paid 300 LKR (approximately £1.30).

Some plantations use different wage models, such as paying staff monthly and offering temporary loans to employees.

The majority of Sri Lankan tea workers are ethnically Indian Tamils, a people who were transported by the British to work on the plantations.

They differ from Jaffna Tamils who originate from Sri Lanka's north.

Dirt roads connect the workers' housing to the tea plantations.

Tea bushes are grown on steep hillsides a metre apart.

Altitude affects the flavour of the tea, with higher altitudes producing a more delicately flavoured crop.

This is more highly valued than the robustly flavoured tea produced at lower elevations.

Veteran tea-pickers often have rough callouses on their hands.

The difficult physical nature of the work is causing a shortage of young tea-pickers.

Many daughters are choosing to work in garment factories, or abroad in domestic roles, rather than the fields of the plantations.

There can be four different levels of hierarchy on a small plantation, ranging from the owner down to tea-pickers.

Each layer supervises the level below it.

Some of the houses the workers live in were built by the British during a housing boom in the 1920s when about 20,000 rooms were built for tea-pickers.

The buildings have changed little since.

Families raise their children in a village setting in colourful barracks-style houses.

Many buildings only have electricity or running water for a few hours each day, or do not have them at all.

Many daily tasks such as washing or bathing are carried out in streams and rivers.

Some areas of housing are supplied with water only once every three days which must be collected in containers.

Tea-pickers and other labourers start work at 7.30am.

In plantation communities, children often have to walk several kilometres to school.

Tea-picking earns relatively low wages, so some tea plantation families have family members who work abroad in the Middle East, or in other cities around Sri Lanka, who send money back home.

Women who labour on the plantations also have household duties such as cooking, cleaning and taking care of children.

The fresh tea leaves are taken to a factory near the plantation for processing, like the one seen below near the Sri Lankan city of Kandy.

'Withering' is the first step, requiring the blowing of dry air to extract moisture from the leaf, which gives it a pliable texture.

A batch of 18kg of fresh leaves can yield 5kg of Ceylon tea after it has been processed in plantation factories.

A rolling machine then twists the withered leaves and begins the fermentation process, which starts to develop the distinctive flavour.

The machinery used in the tea processing is often up to 100 years old.

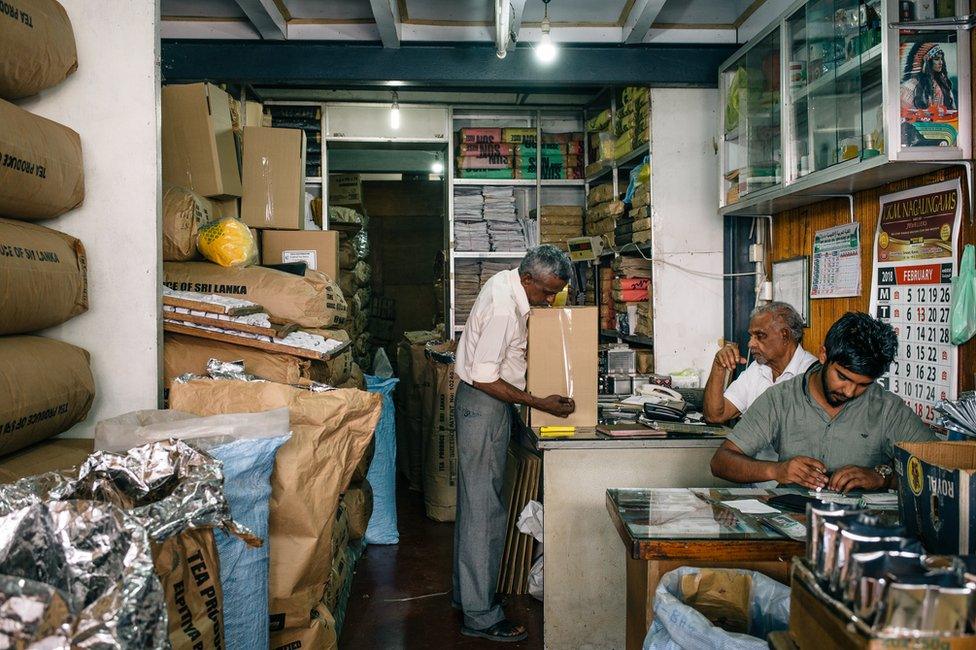

Finished tea is separated by leaf size, and packaged in bulk bags to be sent for auction in Colombo, the capital of Sri Lanka.

Ceylon tea is not just an export, it is an essential part of Sri Lankan daily life, consumed by office workers, labourers, students, and everyone in-between.

All photos: Schmoo Theune

- Published28 November 2014

- Published23 April 2012

- Published4 October 2011