Rwanda genocide: Treating the trauma 26 years on

- Published

Photojournalist Chrystal Ding visited counselling sessions in Rwanda to document the ongoing treatment of those who survived the genocide of 1994.

She spent two weeks in Rwanda taking portraits and landscape photos and collecting handwritten responses from participants in the sessions.

A counselling group in Gatsibo District, Eastern Province, Rwanda

Warning: Some readers may find details in this article upsetting.

In just 100 days in 1994, about 800,000 people were slaughtered by ethnic Hutu extremists. They were targeting members of the minority Tutsi community, as well as their political opponents, irrespective of their ethnic origin.

"I was three years old in 1994, and so I was curious about what happened to survivors of a similar age to me," says Chrystal. "What does recovery from the Rwanda genocide look like now?"

Hillside farmland and homes in Rwanda

Sitting in on five sessions led by Rwandan counsellors, Chrystal heard many stories of horror as the participants recalled the trauma they had experienced as children. Many lost their parents and siblings.

"As someone who lives with their own ongoing mental health difficulties, which I have to keep tabs on, this photography project has been hard," she says.

"I don't think I could be prepared for how affecting it was - just to hear story after story of horrible things happening to people."

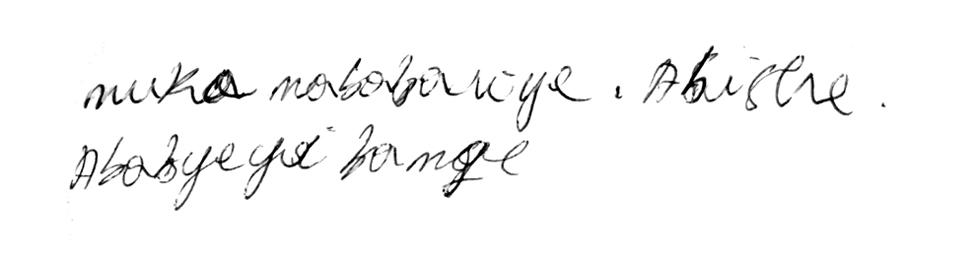

One of the handwritten notes collected by Chrystal. The question asked: "What has helped you through difficult times?" The answer, written in Kinyarwanda: "It's because I forgave those who killed my parents."

Her photography project, entitled Yours is Going to Be Healed As Well, was funded by a bursary from the Rebecca Vassie Memorial Award, and is in association with Survivors Fund (Surf), the organisation which set up the counselling.

A portrait of Denise in Gatsibo District

"It struck me that one of the reasons people feel they can't talk about their experiences is that on a national level people do not say 'Tutsi' and 'Hutu'," Chrystal says.

"The narrative is: 'We are all Rwandan', and it's 'one nation, one people'."

Chrystal explains that another reason people feel inhibited from talking about their memories is because survivors and perpetrators returned to the same places after the genocide, to their villages and communities.

"There is a lot of hurt on all sides… some of the Hutu may still hold on to extremist views based on ethnic divisions. Some may want to ask for forgiveness. On either side people are not clear who they can trust with their stories."

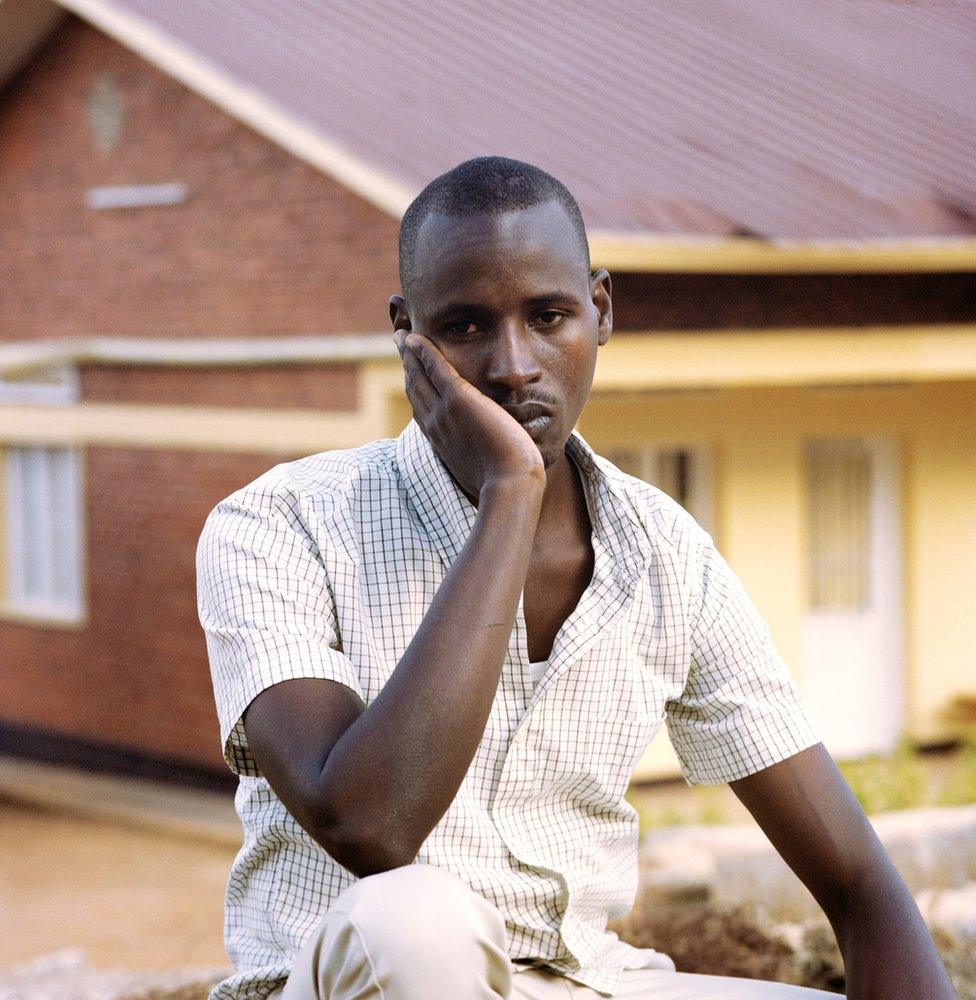

Jean-Marie Viany, in Gatsibo district, told Chrystal: "What happened to me [may] help others."

Chrystal wondered if not being Rwandan would be an issue, when joining the counselling groups.

"I asked Surf if it's going to be problematic having a Chinese-British person turning up and asking them to tell all these stories about the worst things that have ever happened to them.

"[They] said actually it's easier me not being Rwandan, because I am clearly an outsider and there is no risk that what they said would be shared around the community in a way that would impact [on] their daily lives.

"It's a strange case of it being harder to talk within your own community than it is to an outsider."

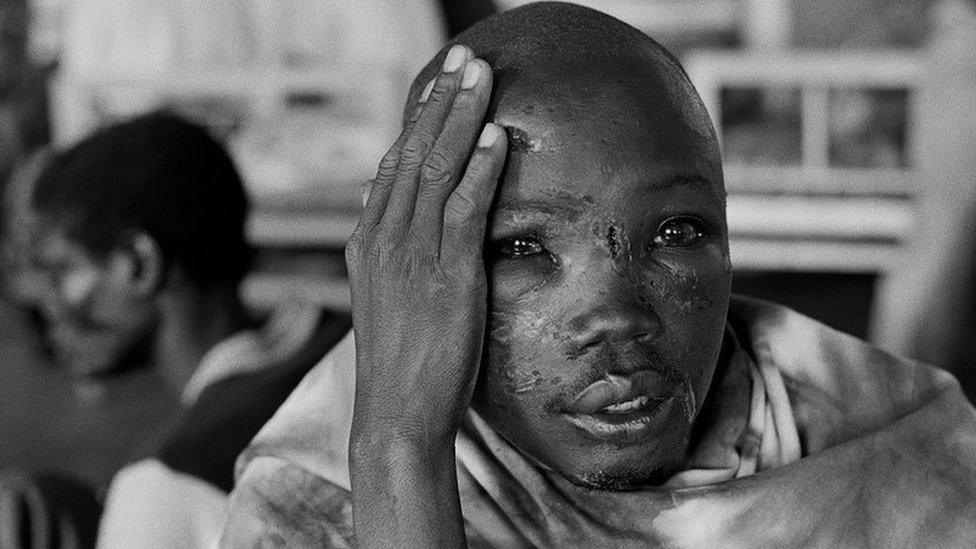

One of the participants who shared her story was Patience*, 35, seen below.

A portrait of Patience

Patience was nine years old when the genocide happened in 1994. Her father hid her along with her siblings, but she was the only one to survive. She says she repeatedly hears the sound of them crying as they were murdered and the mental images of their bodies leave her unable to sleep.

"I think she has a lot of anger," says Chrystal. "She has a house now. People say to her: 'Why do you not smile more, you have a very nice house, why are you not happy?'

"She said: 'The reason I never smile is I have a lot of things I'm always thinking about, so my house is a small thing, and not enough to make me smile.'"

Rwanda's capital city Kigali at dusk

Patience explained that she has suspicions about the involvement of a man in the community in the murder of her father.

"She told one story about how this man used to walk around wearing her father's trousers and shoes. Her father has been missing since the genocide and no-one knows where his body is.

"She would ask the man: 'Where did you get those shoes?' and the man would say: 'Oh your father must have left them in the church before he disappeared'.

"So she went to the church and asked: 'Did my father leave his shoes?' They said he wasn't there at that time.

"She is convinced this man killed her father and took the shoes from his body, and knows where he is buried and won't tell her.

"There's a sense of unresolved anger."

A splintered tree by the roadside, seen during Chrystal's travels around Rwanda

In the counselling sessions, the kind of psychiatric terminology heard in many other parts of the world is not used.

"A lot of the symptoms they describe might be very similar to what we would classify as depression or PTSD.

"In some ways I thought the way they talked about things was quite freeing. They would say things like: 'Who is responsible for your happiness, is it you or somebody else?'

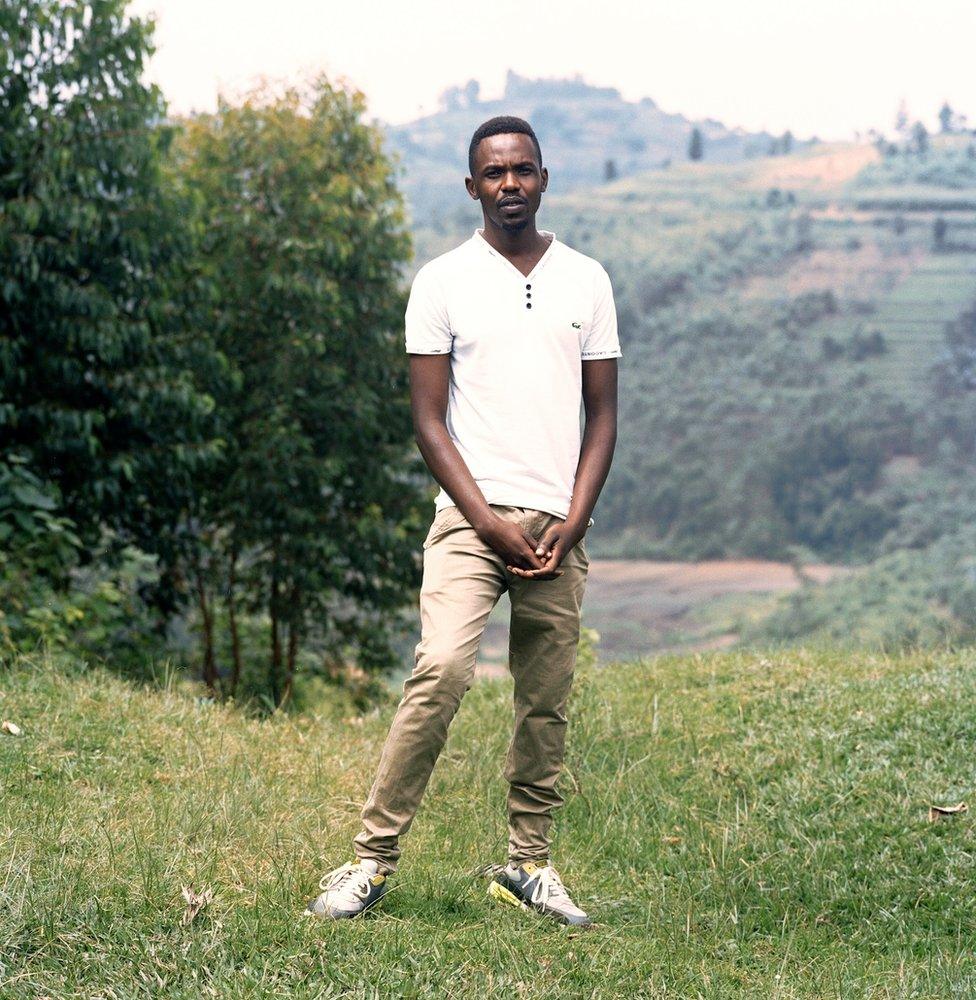

A portrait of Faina in Kibeho, a small town in the south of Rwanda

"[The participants] would talk about how they don't want to be alone when they are experiencing memories of the trauma, and they discussed how they should reach out to a neighbour when they need to.

"The discussions boiled down to the concepts of their trauma, rather than the clinical terminology. They were talking about the same things, in terms of actual experience."

A portrait of Prudent, a leader of one of the counselling groups in Kibeho

Another participant who Chrystal met and photographed was Claudine*, 38, seen below.

A portrait of Claudine

Claudine was 13 when she experienced the genocide. She has since struggled with mental health difficulties, and has had a number of children.

"I visited her at home, and I can't overemphasise her sweetness. She just had this gentleness to her, which is more what you expect from a 13 or 14-year-old. [It was] this kind of delicacy and vulnerability, where you just want to do what you can to show her love."

After a previous suicide attempt, Claudine is trying to rebuild her life with the counselling group.

Chrystal says of Claudine: "When you've not completed school, and therefore are not able to support yourself, there is layer upon layer of vulnerability.

"As I was visiting her house, she said she wanted to give me a photo of her with her son.

"I asked if this was the only copy she had, and she said: 'Yeah yeah, it's a gift'. I said that if this is the only copy you have, then you must keep it.

"She had a generosity of spirit and innocence."

Some of the participants travel long distances to attend the counselling sessions, walking up to five hours to be there.

An issue that Surf is trying to address is the need for childcare for the mothers who are forced to bring their babies and children with them.

"You'd have these tiny children listening to stories about rape for a couple of hours every week, and that can't be good for them to be exposed to that," says Chrystal.

However, those taking part feel the benefit of the counselling, including Patience, who told Chrystal that when she is telling her story, she feels "happy, and my heart feels good".

The counselling group in Kibeho, which grew from 20 to 40 people

Chrystal found that the project affected her personally.

"I haven't stopped thinking about all of the people I met… they're incredible individuals. I still dream about Rwanda, and I suspect I'll be back at some point."

Rwandan farmland

*Names have been changed.

Photos by Chrystal Ding. Interview by Matthew Tucker.

- Published3 December 2018

- Published4 April 2019