Rwanda genocide: 100 days of slaughter

- Published

In just 100 days in 1994, about 800,000 people were slaughtered in Rwanda by ethnic Hutu extremists. They were targeting members of the minority Tutsi community, as well as their political opponents, irrespective of their ethnic origin.

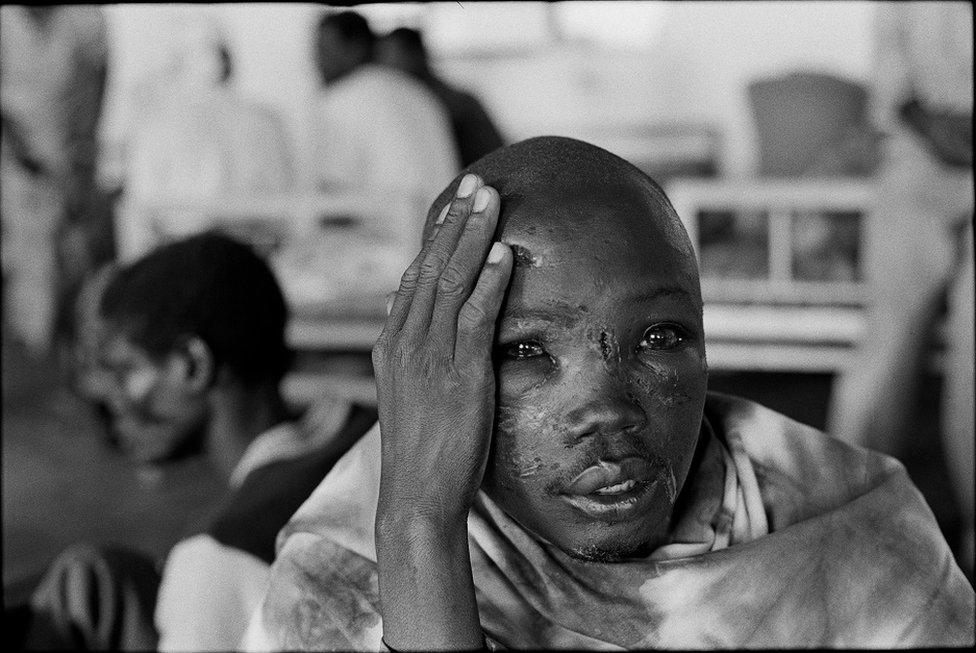

Warning: Contains graphic images.

How did the genocide start?

About 85% of Rwandans are Hutus but the Tutsi minority has long dominated the country. In 1959, the Hutus overthrew the Tutsi monarchy and tens of thousands of Tutsis fled to neighbouring countries, including Uganda.

Between April and July 1994, an estimated 800,000 Rwandans were killed in the space of 100 days.

A group of Tutsi exiles formed a rebel group, the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), which invaded Rwanda in 1990 and fighting continued until a 1993 peace deal was agreed.

On the night of 6 April 1994 a plane carrying then-President Juvenal Habyarimana, and his counterpart Cyprien Ntaryamira of Burundi - both Hutus - was shot down, killing everyone on board.

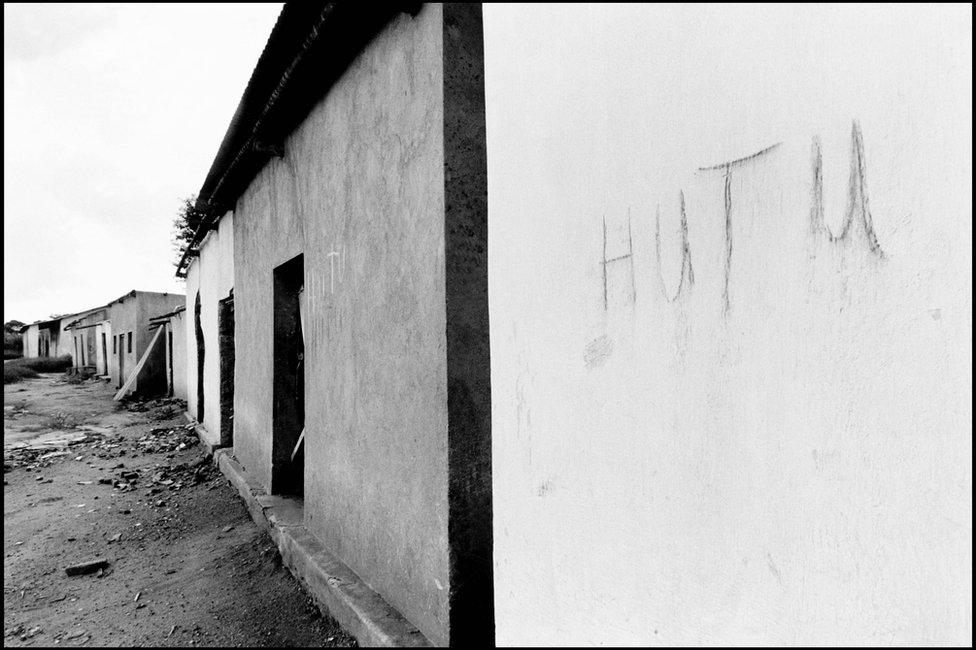

Hutu extremists blamed the RPF and immediately started a well-organised campaign of slaughter. The RPF said the plane had been shot down by Hutus to provide an excuse for the genocide.

How was the genocide carried out?

With meticulous organisation. Lists of government opponents were handed out to militias who went and killed them, along with all of their families.

Neighbours killed neighbours and some husbands even killed their Tutsi wives, saying they would be killed if they refused.

At the time, ID cards had people's ethnic group on them, so militias set up roadblocks where Tutsis were slaughtered, often with machetes which most Rwandans kept around the house.

Thousands of Tutsi women were taken away and kept as sex slaves.

Why was it so vicious?

Rwanda has always been a tightly controlled society, organised like a pyramid from each district up to the top of government. The then-governing party, MRND, had a youth wing called the Interahamwe, which was turned into a militia to carry out the slaughter.

Weapons and hit-lists were handed out to local groups, who knew exactly where to find their targets.

The Hutu extremists set up a radio station, RTLM, and newspapers which circulated hate propaganda, urging people to "weed out the cockroaches" meaning kill the Tutsis. The names of prominent people to be killed were read out on radio.

Even priests and nuns have been convicted of killing people, including some who sought shelter in churches.

By the end of the 100-day killing spree, around 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus had been killed.

Did anyone try to stop it?

The UN and Belgium had forces in Rwanda but the UN mission was not given a mandate to stop the killing.

A year after US troops were killed in Somalia, the US was determined not to get involved in another African conflict. The Belgians and most UN peacekeepers pulled out after 10 Belgian soldiers were killed.

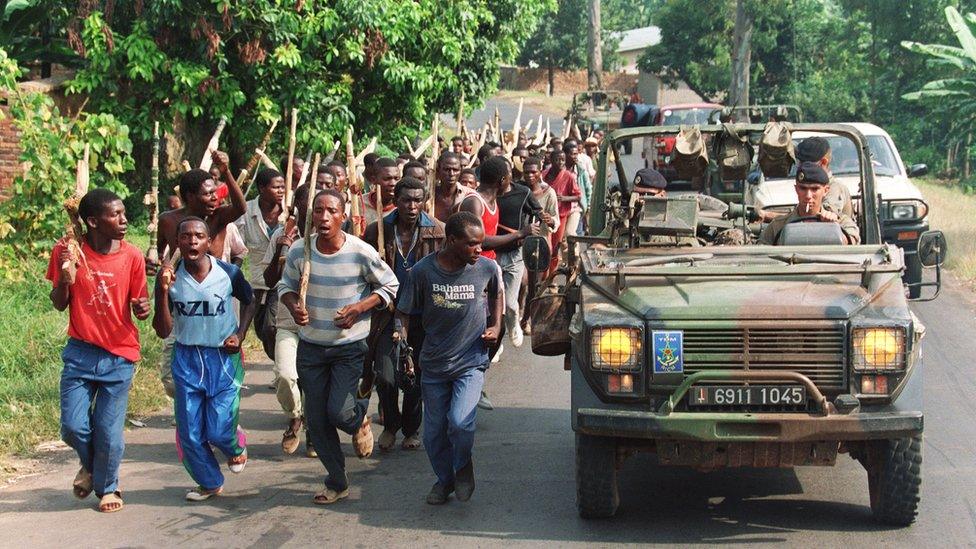

The French, who were allies of the Hutu government, sent a special force to evacuate their citizens and later set up a supposedly safe zone but were accused of not doing enough to stop the slaughter in that area.

French forces in Rwanda were accused of not doing enough to stop the killing

Paul Kagame, Rwanda's current president, has accused France of backing those who carried out the massacres - a charge denied by Paris.

How did it end?

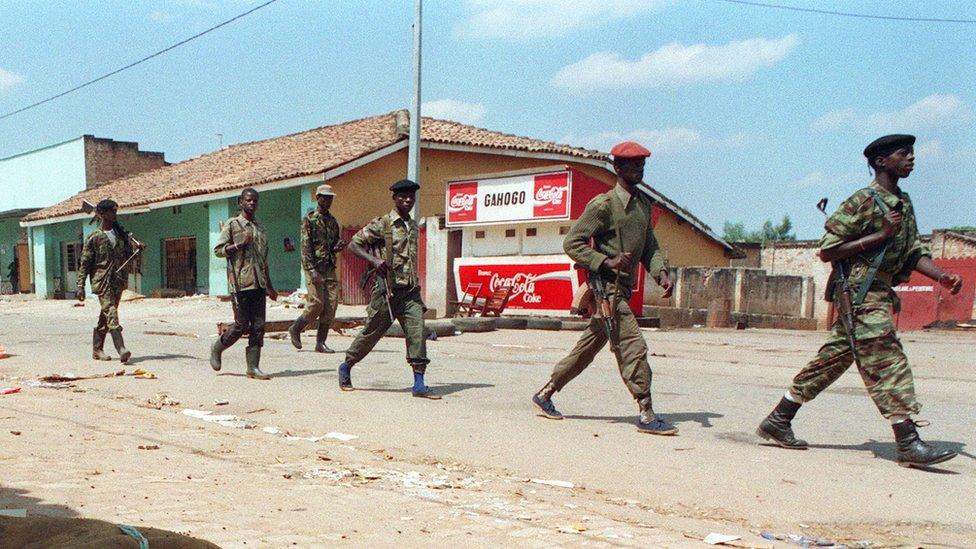

The well-organised RPF, backed by Uganda's army, gradually seized more territory, until 4 July 1994, when its forces marched into the capital, Kigali.

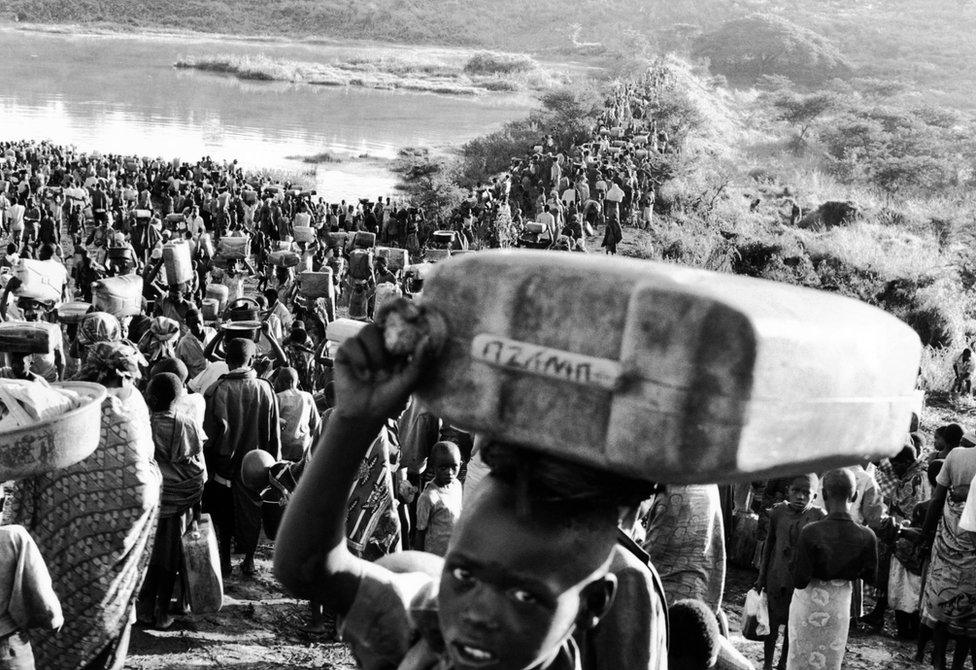

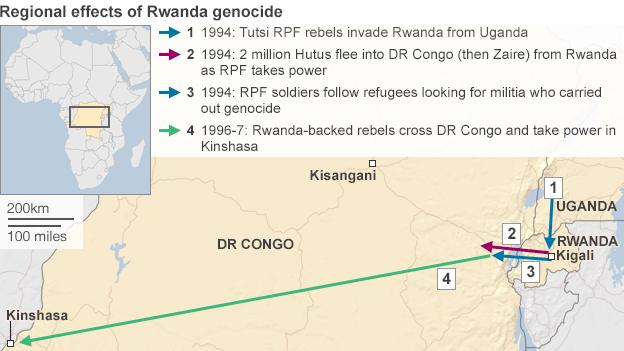

Some two million Hutus - both civilians and some of those involved in the genocide - then fled across the border into the Democratic Republic of Congo, at the time called Zaire, fearing revenge attacks. Others went to neighbouring Tanzania and Burundi.

Human rights groups say RPF fighters killed thousands of Hutu civilians as they took power - and more after they went into DR Congo to pursue the Interahamwe. The RPF denies this.

In DR Congo, thousands died from cholera, while aid groups were accused of letting much of their assistance fall into the hands of the Hutu militias.

What happened in DR Congo?

The RPF, now in power in Rwanda, embraced militias fighting both the Hutu militias and the Congolese army, which was aligned with the Hutus.

The Rwanda-backed rebel groups eventually marched on DR Congo's capital, Kinshasa, and overthrew the government of Mobutu Sese Seko, installing Laurent Kabila as president.

But the new president's reluctance to tackle Hutu militias led to a new war that dragged in six countries and led to the creation of numerous armed groups fighting for control of this mineral-rich country.

Eastern DR Congo has suffered decades of unrest as a consequence of Rwanda's genocide

An estimated five million people died as a result of the conflict which lasted until 2003, with some armed groups active until now in the areas near Rwanda's border.

Has anyone faced justice?

The International Criminal Court was set up in 2002, long after the Rwandan genocide so could not put on trial those responsible.

Instead, the UN Security Council established the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda in the Tanzanian town of Arusha to prosecute the ringleaders.

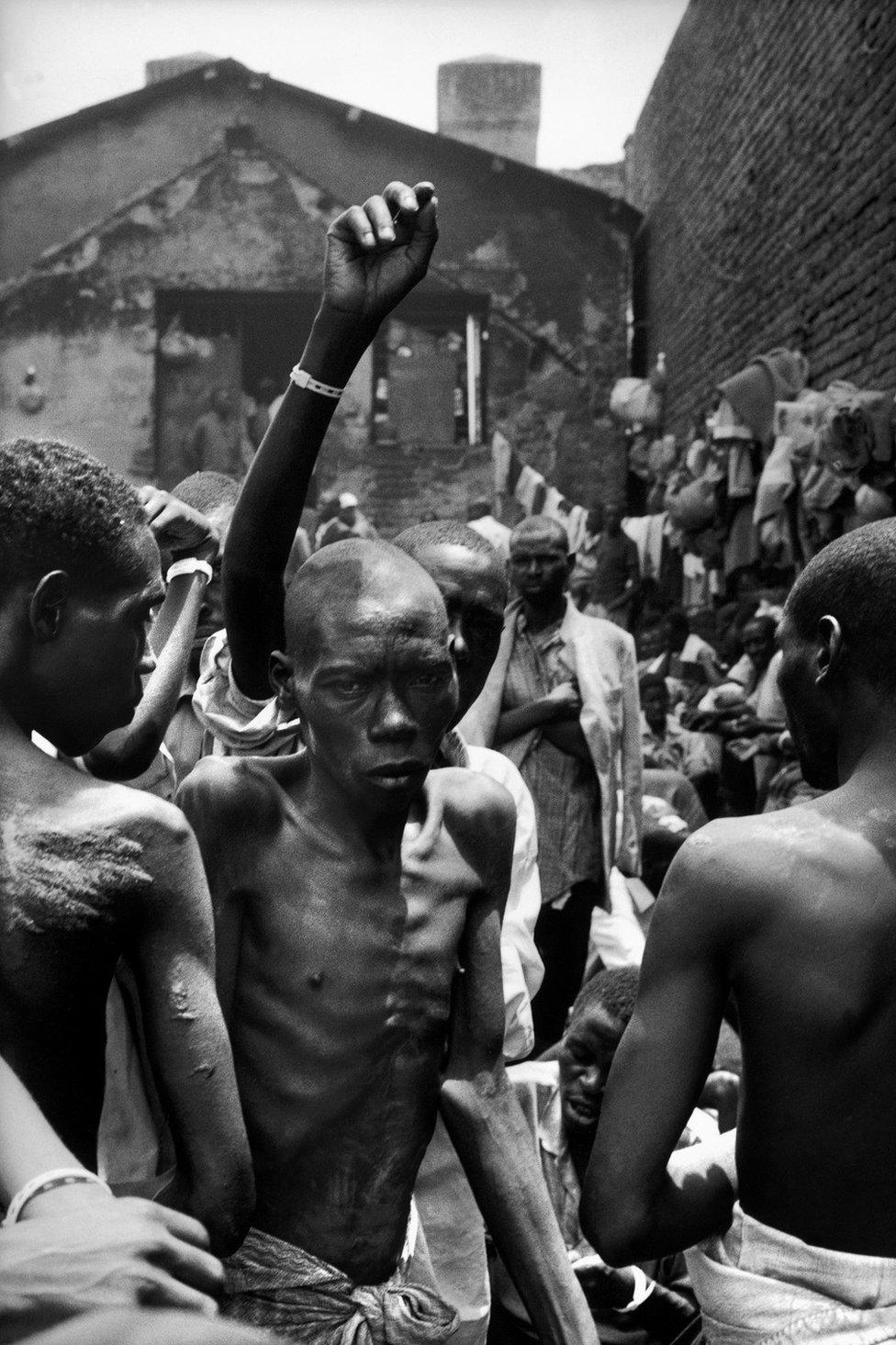

Prisons were overcrowded in the wake of the genocide

A total of 93 people were indicted and after lengthy and expensive trials, dozens of senior officials in the former regime were convicted of genocide - all of them Hutus.

Within Rwanda, community courts, known as gacaca, were created to speed up the prosecution of hundreds of thousands of genocide suspects awaiting trial.

Correspondents say up to 10,000 people died in prison before they could be brought to justice.

The gacaca hearings gave communities a chance to face the accused

For a decade until 2012, 12,000 gacaca courts met once a week in villages across the country, often outdoors in a marketplace or under a tree, trying more than 1.2 million cases.

Their aim was to achieve truth, justice and reconciliation among Rwandans as "gacaca" means to sit down and discuss an issue.

What is Rwanda like now?

President Kagame has been hailed for transforming the tiny, devastated country he took over through policies which encouraged rapid economic growth. He has also tried to turn Rwanda into a technological hub and is very active on Twitter.

Kigali has the reputation for being one of Africa's cleanest cities

But his critics say he does not tolerate dissent and several opponents have met unexplained deaths, both in the country and abroad.

The genocide is obviously still a hugely sensitive issue in Rwanda, and it is illegal to talk about ethnicity.

Paul Kagame (C) won a landslide victory in 2017

The government says this is to prevent hate speech and more bloodshed but some say it prevents true reconciliation.

Charges of stirring up ethnic hatred have been levelled against some of Mr Kagame's critics, which they say is a way of sidelining them.

He won a third term in office in the most recent election in 2017 with 98.63% of the vote.

All photographs belong to the copyright holders as marked

- Published8 April 2014

- Published4 April 2014

- Published5 April 2014