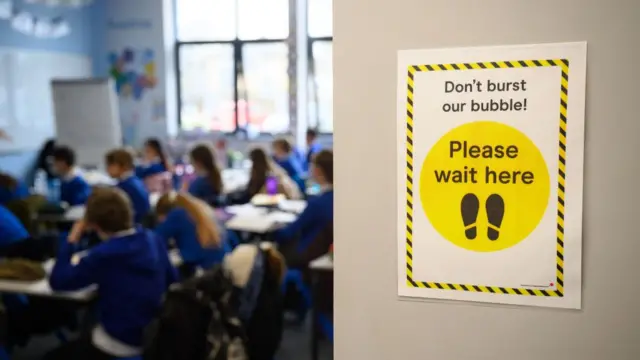

How involved was DfE in reopening - and then closing - schools in January 2021?published at 12:13 BST

Image source, Getty Images

Image source, Getty ImagesDobbin is again returning to Gavin Williamson’s testimony and highlights specifically how “11th hour this decision was” on 4 January to close schools.

Johnson says he can understand why the former education secretary would feel frustrated with schools reopening only to tell them they would be closed again on the same day.

- For context, on 3 January 2021 Johnson said there was "no doubt in my mind that schools are safe" and urged parents to send children to primary schools the following day. On 4 January, Johnson announced a new national lockdown for England, with all schools and colleges closing to most pupils the following day

He tells the inquiry: “We had to make decisions during the pandemic based on our best judgment at the time."

This was the day Johnson realised they couldn’t continue with the policy of opening the schools, he tells Dobbin. Maybe, he says, he should’ve resolved that earlier in his mind but admits that is easier to say in hindsight.

Dobbin then notes Williamson testified he’d received a call at 12:30 on 4 January informing him that schools would close, but says this seems to show that the DfE were not at the table when this decision was made.

In response, Johnson says this is how the government operates in a time of crisis and that he had to think about every single potential Covid victim.

Johnson says his instincts were the same as Williamson’s, but in the end, they had to put the public health issue first.