Farewell peanutspublished at 12:43 BST 15 September 2017

Jonathan Amos

Jonathan Amos

Science correspondent, BBC News, in Pasadena

It's a tradition here at mission control that peanuts are eaten at important moments - such as during a landing on Mars, or, as in this case, the ending of a spectacular orbiter. The voice loop has just suggested the nuts be passed around with just 15 minutes left to impact.

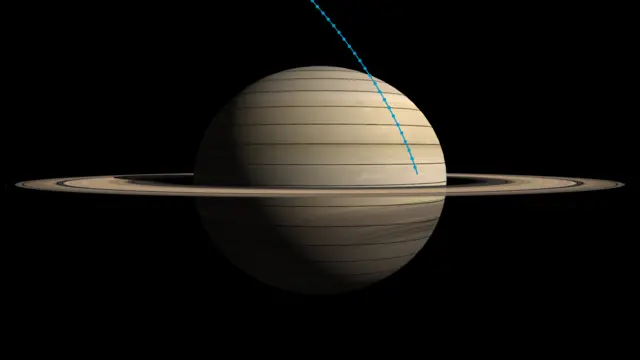

Cassini has just passed 30 degrees North latitude. Even closer now.