Why is Britain braced for a mackerel war?

- Published

Mackerel stocks had recovered well during the past decade

Britain is said to be bracing itself for a re-run of its Cod Wars with Iceland - except this time the fish being fought over is mackerel. Yet, until recently, few were interested in a fish regarded as unclean.

As far as fishing is concerned, relations between the UK and Iceland have been as turbulent as the waters of the North Atlantic where their disputes have been played out.

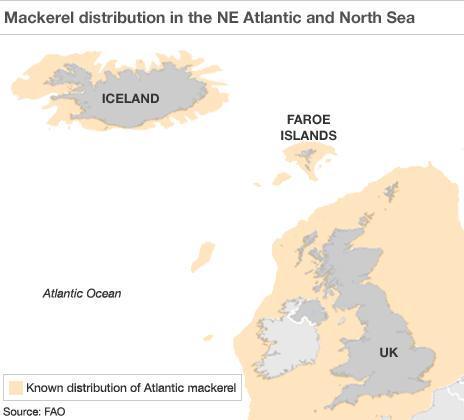

So it is perhaps no surprise to see a British MEP, Conservative Struan Stevenson, calling for an EU-wide blockade, external of Icelandic boats - along with those from the Faroe Islands - in a row over quotas.

However, while rows in the past have been over the coveted and dwindling stocks of cod, this time the nations are clashing over mackerel.

Iceland, which landed practically no mackerel before 2006,, external has allocated itself a 130,000-tonne quota. The Faroes, a collection of islands 250 miles north of Scotland, has tripled its usual entitlement.

The conflict led to a tense stand off at the port of Peterhead last week, when Scottish fishermen blockaded a Faroese trawler - preventing it from landing its £400,000 catch.

Coupled with an EU warning to take "all necessary measures" to protect its fishing interests, it led to comparisons with the last "Cod War" of the 1970s which saw Icelandic gunboats clash with a Royal Navy frigate.

But a war over mackerel in those days would have been inconceivable - a fact that reveals how the oily fish's image has changed.

As recently as the mid-1970s, mackerel had an image problem.

A 1976 survey of "housewives" in Britain by the White Fish Authority demonstrated a reluctance to depart from cod, haddock or salmon. Less than 10% of its 1,931 respondents had ever bought mackerel and only 3% did so regularly. Many fishmongers did not display or even stock it.

"Many housewives had heard that mackerel was a scavenger or that it had a 'bad reputation'," the authority noted.

Mackerel's image problem goes back further, says Dr Robert Prescott, vice-president of the Scottish Fisheries Museum Trust.

"There was folklore suggesting mackerel fed on the corpses of dead sailors. It takes a long time to convince the great British public to change."

It only began being landed in great numbers during the late 19th Century and even then was regarded as "unclean". By the mid-20th Century British-caught mackerel was being processed on Eastern European factory ships and sold for export.

But, Dr Prescott notes, the fish has always been popular among part-time fishermen - largely because "they can't resist any kind of lure" and mackerel is an easy catch.

These days shoppers are perhaps most familiar with the fish as a smoked and vacuum-packed fillet.

Food journalist Nigel Barden says it has become more fashionable, particularly among eco-conscious consumers.

"The health factor is also a huge element. It's an oily fish, rich in omega-3, which is very good for us," says Barden. "They are very versatile. You can bake them, use them as a base for a fish pie, even use them as sushi and sashimi.

"There's nothing better than a fresh, grilled mackerel and we're lucky to have some of the best in the world off our coast."

Whether that remains the case in future decades could depend on the outcome of the current international spat.

Mackerel stocks in the North Atlantic have been carefully managed in recent years, making it something of a rarity in marine stewardship circles - a good news story.

No-one wants a repeat of the collapse in North Sea stocks which saw the volume of catches drop by 90% over a decade, from highs of one million tonnes a year in the 1960s.

Most valuable

The International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (Ices), on whose advice the European quotas are based, classifies stocks as at "full reproductive capacity". However, its latest report, external warns stocks have been significantly overfished since 2007 and the absence of effective international agreements prevents "control of the exploitation rate".

In the last two years, catches in Icelandic waters amounted to 18% of the total haul in the North-East Atlantic - none of which was taken into account before European quotas were agreed.

Smoked mackerel has become increasingly popular

"You can't just add 200,000 tonnes to the quota without expecting some ramifications," says the Marine Stewardship Council's James Simpson. "If the overfishing continues, stock will start to fall below sustainable levels in 2012."

Should that happen, the fish would lose its sustainability certification, knocking consumer confidence and damaging the reputations of fisheries across Europe.

The potential loss to Scotland, where most of the UK's mackerel is caught, is clear. Last year it brought £135m into the economy, making it the Scottish fleet's most valuable fish.

Unsurprisingly Ian Gatt, of the Scottish Pelagic Fishermen's Association, is concerned.

"The mackerel stock has been sustainably managed for many years ensuring that all those involved in the fishery have benefited," he says. "The actions of Iceland and the Faroe Islands could undo all the good work in a matter of months."

'Godsend'

But Iceland and the Faroes see it differently. Both say Europe is stubbornly protecting quotas by refusing meaningful negotiation and, since the fish has gravitated north in recent years, Iceland says it is merely fishing within its own zones.

The Icelandics have little taste for mackerel and for years, says Sigurdur Sverrisson, of the Federation of Icelandic Fishing Vessel Owners, it was "not so much sought after".

But a recent fall in the island's herring catch means it has been "like a Godsend to us".

Seafish, a UK state and industry-funded body which promotes sustainability across all stages of seafood production, acknowledges that something needs to change.

Concerns persist about illegal fishing and discarding of dead undersized fish.

But it says including Iceland in future agreements would bring the overall catch back into manageable levels.

Whether there is political will elsewhere in Europe to agree the quota cuts necessary to allow this to happen, will become clear in the coming months.

- Published21 August 2010

- Published19 August 2010

- Published18 August 2010

- Published10 August 2010