Six steps to survival for Chile miners

- Published

One of the trapped miners, Mario Gomez, 63, wrote a letter to his wife

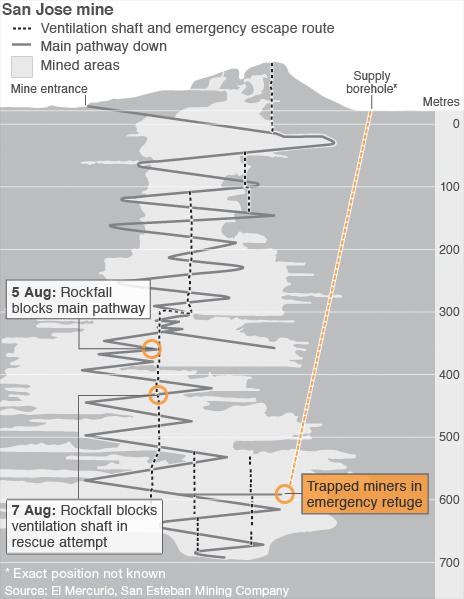

The first supplies have reached the 33 miners trapped 2,300ft (700m) underground in a collapsed mine in Chile. With an estimated four months before they are rescued, what are the key challenges they face?

After the elation of learning they are alive comes the agony of waiting.

Seventeen days after the San Jose copper and gold mine collapsed, the news that all 33 men trapped inside are still alive was greeted with celebrations more than 2,000ft above them.

But their loved ones will probably have to wait until Christmas to see them again, because it will take that long to bore a new hole wide enough to pull them through.

Glucose, rehydration tablets, oxygen and medicine have made their way down from the surface through an 8cm lifeline and into the miners' refuge, which is thought to be about 50 square metres, although some reports say it could be larger.

Trapped miners elsewhere in the world have had to wait to be rescued but very rarely, if ever, for this long. So what are some of the key challenges facing the men in the long months ahead?

Having contact with loved ones

These men have spent 17 days thinking perpetually of those whom they love and fearing they will never see them again, says Dr James Thompson, a senior psychology lecturer at University College London and an expert in trauma.

This forms a tremendous emotional burden for people to carry, so finally being able to say to loved ones "I'm alive" will be a great release, he says.

"I understand they're going to put a telephone line down there so people can have private communication with their families. This is mostly to the good but also to the bad, because it will be intensely emotional and may sometimes make things very hard to bear."

It's important those above ground advise loved ones about what they should say, says Dr Thompson. It should all be resolutely focused on their release and the positive - so talk about the kids doing their homework, for example - and news about family bereavements or illnesses might be better undisclosed.

Rescue updates should be managed in the same way, so if there is a setback and a drill breaks, then only tell the miners about it after it has been fixed.

Enduring the heat

Dave Feickert, a New Zealand mining expert who is advising the Chinese government on improving health and safety, believes the physical challenges that would prove daunting to most people - the cramped conditions, the lack of daylight, the discomfort - will be taken in the stride of miners used to such harsh conditions.

However, one aspect of their confinement he expects to trouble them is the sheer heat they will endure while trapped so far below ground.

Rescuers will need to carefully manage supplies and information

Estimates suggest the men will face temperatures of 32 to 34 degrees Celsius (90 to 93 degrees Fahrenheit), causing great discomfort, sapping their energy and potentially raising tensions among the group.

He suggests it will be important for the crew at ground level to assess whether the heat is dry or humid and try to arrange suitable ventilation.

"The deeper you get, the hotter it becomes," Mr Feickert says. "They'll be used to working in hot conditions, but not for that period of time. It's not going to be very comfortable."

Normally, in such temperatures, an adult would have to drink around four litres of water a day, says Dr Alan Richardson, a lecturer in exercise physiology at Brighton University. It may be difficult to keep them supplied with such a volume.

"If they don't get enough hydration they're going to lose weight through fluid loss," he says. "The low level of oxygen is going to have the same effect."

Keeping active

Although their physical fitness will initially be a physical and psychological advantage, it will not take long for this to deteriorate, says Dr Richardson.

"The main issue they are going to have is muscle wastage by not being able to move as much as they can in everyday life. When they come out, it's going to be like coming off a space flight."

Dr Richardson suggests they should try to do simple isometric exercises - static resistance movements against the wall to work the muscles. However, it is virtually inevitable they will lose tone, sapping them of energy and making them more lethargic.

In one sense, he says, this could have a positive side-effect, helping them sleep. But Mr Feickert says it will be psychologically very important for them to stay active.

"These are very fit guys who are used to a lot of physical activity, if they're suddenly not doing anything they're going to get depressed," he says.

Identifying leaders and allocating tasks

To counteract this boredom, Mr Feickert believes the miners need to organise themselves rotas for performing tasks and chores - everything from clearing rubble that comes through the shaft to cleaning.

"Even if it's work that isn't particularly useful, it's important to morale that they're doing something, plus it takes their mind off being trapped underground."

The ethos of mining and the risks that accompany the profession makes them a self-selecting group better equipped to endure this, says Dr Thompson. And there will probably be natural leaders among the group who can provide "good, optimism-based leadership".

Tasks are important to break up the boredom and create routines, but should also have a practical use where possible. These could include making latrines, requesting items from above such as antiseptic for their hands, washing and disinfecting, and organising a rota for contact with families.

Turning lights on during the day and off at night can help reinforce this cycle.

"They need to have a focus which is practical and somewhat future-orientated."

Keeping the truth from them

The miners have not been told how long they are going to have to wait and Dr Thompson says this is wise in these early stages.

Stress can become intolerable when it appears to be endless, he says, and for the miners there is no safety signal to give, no ending in sight.

"They're going to ask 'how long?' and one way I would go about it is to say 'we don't know that yet but we're going to tell you where we are, this is what we are trying to do. This is the drill that is being brought in.'"

One reason why so many people recover mentally from a car crash is that it is over so quickly, says Dr Thompson. Sending the miners photos of the machine the rescuers are using to get them out would be one way of lifting their spirits as the wait goes on and on.

Avoiding infections

With so many miners in such a confined space, guarding against injury and ill-health will be paramount. But according to Mike Tipton, professor of applied and human physiology at the University of Portsmouth, maintaining sanitary conditions will be a difficult task.

As well as setting up and maintaining a sanitary system, there are other considerations, like having enough light to prevent knocking over a latrine and increasing health risks.

"Long-term survival will depend on the avoidance of infection and injury, sanitation will be an important factor in this regard and require some organisation," he says.

"If you've got 33 miners down there for 120 days, that's a lot of human waste you've got to manage and deal with."

What is more, there is little way of predicting whether further movements of rock pose a risk to the men.

"You also have the risk of further collapses and one of the miners getting hurt," says Prof Tipton.

"If someone is injured or gets sick they can send down medication, but what if it doesn't work? There aren't likely to be many paramedics among 33 miners."

- Published24 August 2010