Home working: Why can't everyone telework?

- Published

- comments

The UK government is suggesting people work from home to avoid travel chaos around the 2012 Olympics, but why hasn't teleworking already taken off, asks Tom de Castella.

Once upon a time teleworking was the future that would free us from the yoke of office life. Armed with phone, computer and internet connection, human potential would blossom in the comfort of our own homes.

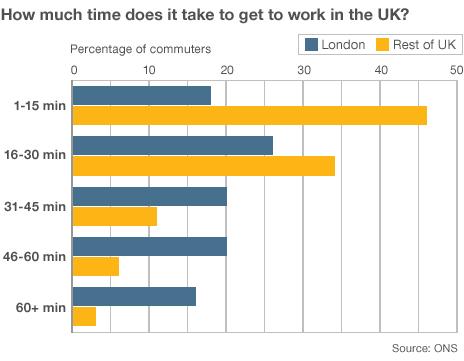

It makes sense. Why travel for hours a day to a central location when you can roll out of bed and start working from your kitchen table with none of the hassle and environmental damage that commuting entails?

Home working is certainly on the rise. A survey of firms by the Confederation of British Industry showed that the number offering at least some teleworking rose from 14% in 2006 to 46% in 2008. Figures later this month are expected to show the trend continuing.

British Telecom was one of the pioneers. It began a telework scheme in 1986, and now has 15,000 homeworkers out of 92,000 employees. The company argues that homeworkers save it an average of £6,000 a year each, are 20% more productive and take fewer sick days.

At HSBC 15,000 out of the bank's 35,000 staff in the UK have the ability to work from home. But that is still less than half the workforce and figures deal only with the means to work from home, they do not indicate full-time home working.

But why isn't there even more working from home?

Home working doesn't suit all jobs or sectors. There are some sectors of the UK economy where teleworking is impossible - retailers, manufacturers and City traders are among those where most people have to be at the workplace. In theory, call centres could allow staff to work from home. In practice, the cost of linking secure databases to thousands of houses stands as a considerable obstacle.

It's a balance, says HSBC spokesman Mark Hemingway. "Cashiers have to be in the branch and we need staff in call centres. But for all the admin work we do actively organise it so that people can work from home." It may involve giving them a laptop, remote working technology or a phone with e-mail but the rewards for the firm are higher productivity, low absenteeism and better staff retention, he says.

Successive governments have pressed employers to bring in more flexible working, which can involve home working. Workers who are carers or parents already have the right to ask their employer for flexible working, although employers are not required to agree to it. The government plans to extend this right to ask to all workers during this parliament, to the annoyance of some employers.

And this week UK Transport Secretary Philip Hammond called for employees in London to work from home during the Olympics next year. The move - intended to ease transport congestion - was criticised by one business group.

"One would have hoped that business is the best judge of where their staff should be," says Alexander Ehmann, head of employment at the Institute of Directors. "It's slightly surprising to read his comments saying that staff should stay away from London. We'd hope that the transport infrastructure is there to allow people to get to work."

But there are some who welcome teleworking. "We should be having more flexible working," says Cary Cooper, Professor of organisational psychology at Lancaster University Management School. "It's not for everyone - you can't build a car at home. But quite a lot of the UK works in the knowledge economy, and for these workers there's no problem."

He notes there is research showing that people are more productive at home, while technology many have - a computer, phone and broadband - allows us to stay in touch with colleagues. There are clear benefits. You do away with long commutes that waste time, cause pollution and raise stress levels. Homeworkers often have more leeway to plan their lives better - picking up the children from school or caring for elderly relatives.

However there are potential drawbacks to working from your kitchen or study. For one thing you're on your own. "It can get a bit lonesome at home and you should eyeball your manager from time to time," he says. "Otherwise without feedback you can drift and lose focus."

Prof Cooper warns that you may slip down the pecking order if you're never in the office. Keeping a clear distinction between home and work is also tricky. And what happens if your computer or internet fails? "If the technology goes down then you're left exposed. Whereas in the office someone will come and fix it."

For Prof Cooper the answer is to find a happy medium of flexible working, with staff alternating between shifts in the office and at home.

Despite research pointing to higher output from home working, there's still a perception from some that it amounts to skiving. When many people were forced to work from home across the UK one snowbound day in November, the Jeremy Kyle show was watched by an extra 200,000 viewers. Indeed some people assert they waste as much time with none of the benefits that chatting to colleagues offers.

"What happens when I work at home is that the first hour is productive and then I start going to pieces," wrote Financial Times work commentator Lucy Kellaway in a column in December. "It is as if I am governed by an internal time-wasting law that says the amount of time wasted in any day is constant."

Indeed for many staff, home is moving to the workplace. Employees now shower and breakfast in the office, hang clothing by their desks and have personal post delivered there, Kellaway argues.

Britain is not alone in pushing for more home working. The US congress recently passed the Telework Enhancement Act, which requires the head of every government agency to establish telework policy for staff.

An employee who works three days a week from home can save $5,878 (£3,775) a year on commuting costs and spare the environment 4000 kilograms of pollutants, according to Telework Exchange, an organisation promoting the practice.

In Britain, managerial prejudice still needs to be overcome. "Teleworking has been seen as an employee benefit, rather than as a good move for business," says Shirley Borrott, director of the Telework Association. "In some cases they think, 'how am I going to know they're working if I can't see them?'"

But Guy Bailey, a policy advisor at the CBI, says that while the trend for home working will continue, it's unlikely to make the office obsolete. "For a large proportion of workers, the demand will always be to work with colleagues. They want somewhere they can bounce ideas off each other and keep things separate from their private life."

There's another problem with working from home. You can't moan about it to the person sitting at the next desk.

Additional reporting by Rajini Vaidyanathan