Does a narrow social elite run the country?

- Published

- comments

After a turbulent week in Westminster, it seems that British politicians from all parties are being drawn from an ever smaller social pool, says broadcaster Andrew Neil. It wasn't always thus, so what's changed?

The resignations of shadow chancellor Alan Johnson and Tory communications director Andy Coulson spell bad news for an already endangered species - political high-flyers from ordinary backgrounds.

Johnson and Coulson are council-house boys who never went to university, but dragged themselves to the top by sheer hard work, ability and ambition. Look at today's top politicians - both on the right and the left - and you won't find many of their kind remaining.

I too was brought up in a council house but was luckier than Johnson or Coulson. I made it to an elite 16th Century grammar school in Paisley and then Glasgow University, a world-class 15th Century institution.

I was part of the post-World War II meritocracy that slowly began to infiltrate the citadels of power, compete head-to-head against those with the "right" background and connections and - more often than not - win. Britain's class system seemed to be changing, a presumption tested in the BBC's new class test, external.

Of course, the public schoolboys still held on to a disproportionate share of the top jobs. But the meritocrats were making great inroads, nowhere more so than in politics - even at the very top.

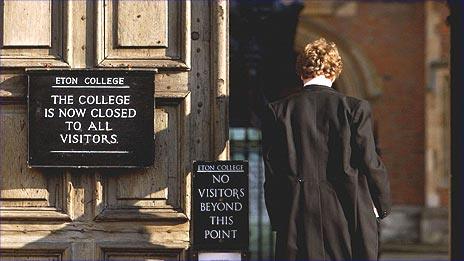

The change was a social revolution. In the 50s and early 60s, Britain had one prime minister after another - Eden, Macmillan, Douglas-Home - who hadn't just gone to public school, they went to the same public school - Eton, naturally.

Then along came Labour's Harold Wilson in 1964, a Yorkshire grammar schoolboy and it looked as if things would never be the same again. For the next 33 years, every prime minister - Labour or Tory - was educated at a state school.

Nobody thought there would never be another public school prime minister, just that a privileged background would no longer matter so much in climbing the greasy pole of politics.

I was pretty sure the meritocracy was here to stay. It never dawned on me that by the start of the 21st Century, it would come to a grinding halt.

Tony Blair, educated at Fettes - Scotland's poshest private school, broke the run of state-educated PMs when he won the 1997 general election.

On the face of it, that was not necessarily significant, Blair presided over the most state-educated, least Oxbridge cabinet in British history. But behind the scenes, the meritocracy was in trouble.

With the demise of the grammar schools, a new, largely public school educated generation was taking over the Tories once more. And Labour was becoming much more middle-class and Oxbridge again.

Just a glance at today's political elite and it is clear the meritocracy is in trouble. Nobody can deny that our current crop of political leaders is bright. But the pipeline which produces them has become narrower and more privileged.

Cameron, Clegg and Osborne all went to private schools with fees now higher than the average annual wage. Half the cabinet went to fee-paying schools - versus only 7% of the country - as did a third of all MPs.

After falling steadily for decades, the number of public school MPs is on the rise once more, 20 of them from Eton alone - five more MPs than the previous Parliament.

Top Labour politicians are less posh than the Tories or the Lib Dems but they are increasingly middle-class, Oxbridge-educated and have done nothing but politics.

Labour Leader Ed Miliband graduated in philosophy, politics and economics (PPE) from Oxford and was pretty quickly working for Gordon Brown. His brother David also did PPE at Oxford and was soon advising Tony Blair.

New shadow chancellor Ed Balls also went to Oxford after private school to do - you guessed it - PPE. It was there that he met his wife, the new shadow home secretary Yvette Cooper, who also happened to be doing PPE as well.

So why has politics become the preserve of the privileged once more?

'Widening gap'

The decline of the unions has clearly cut off one working-class route to Westminster. So has the decline of an affluent, aspiring working class, which seemed to disappear with the end of the Industrial Age.

But our education system must have something to do with it as well. Almost uniquely, Britain has developed a largely egalitarian non-selective state school system alongside an aggressive highly-selective private system. Perhaps it should be no surprise that the top jobs are once again falling into the lap of the latter.

The gap between state and private schools is wide and possibly getting wider. Almost one third of private school pupils get at least three A-grade A-levels versus 7.5% of comprehensive pupils. It is a gap that has doubled since 1998, even though Labour doubled spending on schools.

Some think a return to selection by ability would give bright kids from ordinary backgrounds a leg up. But the 11-plus gave selection a bad name and neither Tory nor Labour politicians want to talk about it.

Maybe they're right but in the 21st Century, could it not be possible to come up with more sophisticated, more flexible forms of selection by ability which consign nobody to the educational dustbin? Could we not create, like the Germans, high quality vocational and technology schools every bit as good as academic hothouses?

Perhaps that's a pipedream, in which case prepare for our politics - already posh again - to become even posher.