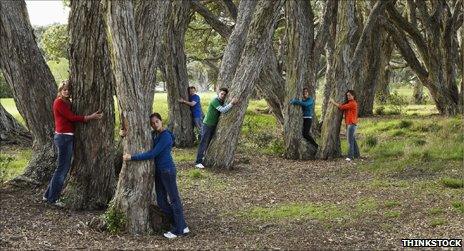

Why are we a nation of tree-huggers?

- Published

- comments

Plans to transfer ownership of many public forests in England have provoked a huge row. But why are we so protective of our woodlands?

It's about the rustling of the leaves and the crunch of twigs underfoot. It's the sensation of the rough bark on your hands and the light dappling into a clearing.

Above all, it's a place where nature takes priority over humans.

For the vast majority of us, living in towns and cities, visiting a forest is the easiest way to escape our mechanised, wipe-clean, ring-roaded civilisation and properly get back to nature.

As the government is finding out, a forest unleashes something deeply primordial in otherwise domesticated, suburban Britons.

Plans to radically change the ownership of some of England's forests have provoked a furious backlash. The government plans to lease large commercial forests to private companies, while allowing community groups to buy or lease forests and encouraging charities to own or manage "heritage" forests. But at the same time it is increasing open market sales of forests.

A YouGov poll suggested that 84% of people were opposed., external to the government's plans, with one pressure group saying it had collected 400,000 signatures on a petition.

Such august public figures as Dame Judi Dench, poet laureate Carol Anne Duffy and the Archbishop of Canterbury have spearheaded a campaign against the move, and even the Sunday Telegraph - not generally noted for its antipathy to free-market principles - denounced the privatisation in a leader., external Critics fear public access - despite the government's assurances - could be undermined.

Ministers insist giving community and civil society groups the opportunity to buy or lease forests will make the estates more responsive to the needs of the public.

But whatever one's views on the proposals, the hostility expressed by middle England and the pointed disavowal of the plans by devolved administrations in Scotland and Wales illustrates how protective the British are of their trees.

Indeed, it is a response that tells us much about a country in which 90% of the population live in urban areas.

Woodlands are hugely popular, with some 40 million visits made to publicly-owned forests in England alone each year. The Forestry Commission says its land across Britain - which does include non-wooded areas - attracts more visitors than does the combined seaside of this island nation.

And as the allure of the wilderness attracts walkers, cyclists and nature lovers in their multitudes, it hardly seems fanciful to speculate that there might be something deep in the national psyche that is roused by trees.

They loom heavily, after all, in our national myths and legends. Sherwood Forest is a symbol of anarchic freedom for Robin Hood and his outlaws. Conversely, to Macbeth, the march of Birnam Wood is redolent of nature at its most menacing and terrifying.

For biologist and writer Colin Tudge, author of The Secret Life of Trees: How They Live and Why They Matter, forests are an intrinsic part not just of British culture, but of the human psyche.

"There's this very primitive response, " he says. "All of us like trees as aesthetic things: they are beautiful.

"Essentially, we [British people] are woodland creatures - we like to live on the edge of woods. We all know that life surrounded by trees is so much more comfortable."

This apparent affinity has not prevented various arboreal misconceptions taking grip, however.

In his seminal book Woodlands, Cambridge botanist Professor Oliver Rackham dismisses the notion that medieval Britain was one big forest wilderness of vast, looming oaks and that the industrial revolution signalled a nationwide orgy of tree-chopping.

In fact, the high point of forestation was sometime in the Bronze Age. Most oaks in the Middle Ages were smaller than they were today and, Rackham argues, industrialisation and urbanisation actually acted as a catalyst for preservation.

Indeed, since the creation of the Forestry Commission in 1919, the proportion of the UK covered in trees has risen from 4% to 12%. Nonetheless, this remains well below the rest of the EU, where the figure is typically closer to 30%, according to the Woodland Trust.

According to Rachel Johnson, journalist and president of the Save England's Forests campaign, it is this scarcity that makes the woods so precious to the suburban nature-lovers who form the backbone of her crusade.

"They want to escape," she says. "Most of us live in cities and go from A to B in our cars or on public transport.

"The mature forest is really our equivalent of the rainforest."

However, not all woodlands enthusiasts are so hostile to the proposals.

Tom Curtis, director of LandShare, a not-for-profit organisation which advises foresters and landowners on managing their resources, believes they have the potential to give the people who use the forests more of a say.

"The plans could potentially give people more of a connection with their local woods," he says.

"However, I think it's natural that people feel so strongly about our forests. They realise that, deep down, we are absolutely dependent on them for survival."

Whichever way the debate plays out, the passions stirred by the subject are unlikely to go away. And in this regard, whichever side ultimately triumphs will be the one that manages to see the wood for the trees.