Stradivarius burden: Life with a precious instrument

- Published

A stewardess once put Viktoria Mullova's Stradivarius in the hold

Three people have pleaded guilty to the theft of a £1.2m ($1.95m) Stradivarius violin, stolen while a top musician was distracted in a London sandwich shop. The case has highlighted how classical music performers travel the world with instruments worth thousands - and occasionally millions - simply hanging by their sides.

Few people would dream of carrying around cash to the value of even the bow that was also snatched last December - that alone was worth about £62,000 ($100,000) - never mind the 300-year-old violin itself.

Violinist Stephen Bryant, leader of the BBC Symphony Orchestra, says taxi drivers' first question when they hear what's in his case is about its value. They are always stunned by the answer.

Modest only in comparison to the seven-figure price tags of the likes of a Stradivarius, Bryant's violin is valued at close to £250,000 ($406,000).

"It's quite a hard thing for a lot of people to grasp that you can carry around something as valuable as that," he says.

What may also be hard to grasp is that most musicians' strategy for looking after these incredibly precious instruments comes down to little more than common sense.

"Make sure you personally accompany your instrument at all times," says an advice sheet from Lark Group, specialists in music instrument insurance. "Make sure that they are always in your line of sight."

"There's certainly no stipulation that you have got to have it tied to your body or anything like that," says Suzanne Beney, Lark's head of marketing. "If you are telling people to strap it to themselves, are you drawing more attention to it?"

Thefts of instruments are rare, she adds, and usually carried out by opportunists with no idea of the items' worth.

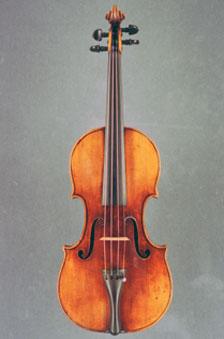

In fact, the most precious instruments have almost zero sell-on value. Each example of a Stradivarius - of which there are just a few hundred in the world - is almost impossible to re-sell because it is so recognisable.

"You would be lucky if you got a fiver down the market," says Ariane Todes, editor of The Strad magazine.

"For some of the really big stars, they do actually have instrument minders - they will literally have a minder who carries the violin, or who watches them as they carry it."

However, for most musicians it seems that maintaining eye contact, or better still physical contact, is how they keep their instrument safe when they are out. Bryant always rests a foot on his violin case whenever he has it with him in a pub or restaurant.

The Stradivarius is still missing

But musicians also speak of a heightened sense of awareness towards their instrument, based on an extraordinary bond beyond that with any ordinary possession.

"They are objects of devotion for musicians," says Bryant. "You are carrying about something that is very valuable but you are also carrying about something that you are emotionally attached to as well, because it's your way of expressing yourself."

He adds: "It's a bit like taking a child around. If you get on a train you make sure you hold the child's hand. If you have got an expensive violin, you just make sure you have got hold of it."

To lose the violin he has been playing for about 15 years would be traumatic, he says, and that trauma could last for years as he searched for a satisfactory replacement.

Lark Group offers cash settlements rather than replacements for lost or damaged instruments. "It means people can find a replacement at their own pace," says Ms Beney. "It takes a lot of time to find an instrument that they want to play and is right for them."

There are famous instances of performers being separated from instruments worth millions by simply leaving them behind somewhere. In 2008, violinist Philippe Quint gave a private performance to New York taxi drivers as thanks for the return of the 285-year-old Stradivarius which had been left in a cab.

Russian violin virtuoso Viktoria Mullova describes two scares that were the result of other people handling her violins.

A flight stewardess, without saying anything, once removed the instrument from the cabin compartment and placed it in the plane hold. "It could have been smashed," says Mullova. "I was very lucky that nothing happened to it. That was a Strad - it was a terrifying moment."

Another time, a friend who had offered to carry Mullova's violin then forgot to pick it up when he got out of a taxi - fortunately Mullova spotted the mistake before it was too late.

"That happened because he is not used to looking after a violin. I am used to it all the time," she says. "I would prefer not to give it to anyone else to carry. They are not used to remembering to have it all the time."

She admits that she is reluctant to entrust even her husband with her violin.

"It's always better if I have it myself."