Titanic: How can a disastrous ship be celebrated?

- Published

- comments

More than 1,500 people died when the Titanic sank. So why is the centenary of its launch being proudly celebrated in Northern Ireland, asks Tom de Castella.

No other ship comes close to rivalling the gigantic shadow cast by the Titanic. A hundred years after its completion, it's still the most iconic vessel to have set sail.

Its tragic maiden voyage has become shorthand for catastrophic hubris - the "unsinkable" ship that hit an iceberg and sank, causing the deaths of 1,503 passengers and crew. And yet in one corner of the UK, the Titanic is a byword not for disaster but a source of pride and nostalgia.

When its hull was launched at Belfast's Harland and Wolff shipyard on 31 May 1911, it was the largest ship in the world, measuring 886ft (270m) long.

And in Northern Ireland that's where the story ends, says Mick Fealty, editor of the news site Slugger O'Toole.

Rather than a maritime disaster, the Titanic is an engineering triumph. There's a common Belfast joke, says the Irish writer Ruth Dudley Edwards, that taps into this feeling: "It was fine when it left us."

Behind the joking there's a serious point, Fealty says. The shipyards in those days employed tens of thousands of workers while Belfast also had the world's largest rope works and the huge textile machinery firm Mackies.

"The pride is about looking back to the golden days. The Titanic was the pinnacle of Belfast's industrial glory," he says. This was in the days before partition when the majority Protestant city wore industrialisation as a badge of pride, differentiating itself from the agrarian, Catholic and rural south.

"Its industrialism was a real exception on the island of Ireland. Dublin was Edinburgh to Belfast's Glasgow," says Fealty.

Not only that, its industrial might made Belfast a crucial partner in the British empire, says Jonathan Tonge, professor of politics at Liverpool University. "Many northern Irish Protestants say the empire was built on the Northern Irish ship building industry."

Dudley Edwards, author of The Faithful Tribe, about the Orange Order, says the Titanic is a link to a time when the Protestant working class built things.

East Belfast, where the shipyards were located, was staunchly unionist.

Contrary to legend, Catholic workers were involved in building the Titanic. It wasn't until 1920 that Catholics were forced out of the shipyards en masse. But they had been a minority in a mainly Protestant workforce, and were typically in unskilled roles.

Under the effective segregation of the workforce, many skilled industrial jobs were reserved for the Protestant working class.

Catholic communities without such guaranteed industrial jobs encouraged their children to better themselves through education, Dudley Edwards says. But protestant east Belfast, where the shipyards were located, relied on their privileged access to industrial jobs.

"It's all gone now. Those communities are now in a pretty terrible state," says Dudley Edwards. "Everyone in this community is very nostalgic about it."

The achievement of building the liner has not always been celebrated by everybody.

There was hostility to the Titanic legacy from Catholics, says Liam Kennedy, professor of history at Queen's University Belfast. The fact that most of those who worked on it were Protestant was significant. But at a deeper level it was a rejection of the industrial achievements of east Belfast's Protestant business class and workers, he says.

Prof Kennedy remembers how he first heard about the Titanic at school in County Tipperary, in the Republic of Ireland, during the early 1960s.

"The schoolmaster gave us the shipping number of the Titanic and said if you look at in the mirror it says 'No Pope'. And I remember it really did look like that."

Prof Jonathan Moore, lecturer in Irish politics at London Metropolitan University, recalls the experience of an American student who recently visited Belfast's Titanic exhibition.

"She'd gone to the Falls Road and was talking to some Sinn Fein supporters about how brilliant the exhibition was. One of them turned to her and said 'Excuse me, that's not part of our history'."

Pride in the Titanic can be seen in murals in Protestant areas

There are some who might wonder if the celebration of a ship associated with such loss of life is "baffling and bizarre", argues Prof Tonge. "Here's a ship that took three years to build and two-and-a-half hours to sink. Yet 100 years later people are celebrating it. It's jaw dropping."

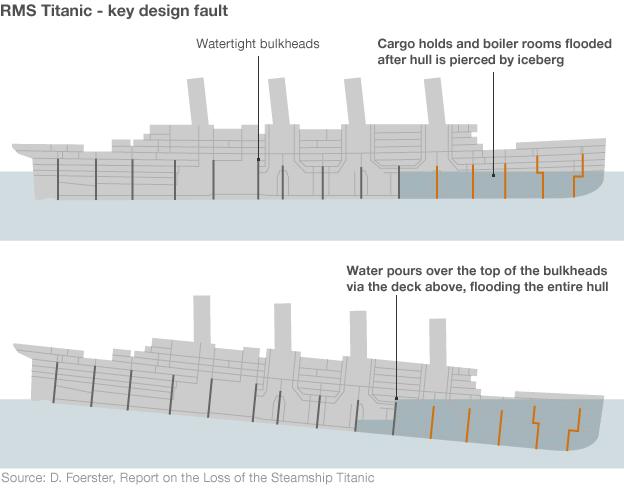

Far from an engineering triumph the ship's design was flawed. Paul Louden-Brown, vice president of the Titanic Historical Society,has writtenof how the design was a clumsy scaled-up version of smaller vessels and ignored the cutting-edge technology of Cunard's liners.

And the builders' claim that it was "practically unsinkable" had totally ignored the effect of an iceberg colliding with the side of the hull.

But you won't hear that side of the story much in Belfast, notes Dudley Edwards.

In the long run that might be for the best. The ship's fame has spawned the Titanic Quarter, a £7bn development which began in 2006 to turn the old shipyards into a mile-long waterfront of shops, offices and bars.

The "Titanic" brand has been used for a massive redevelopment

"They're trying to give status to an area and pay homage to its history before it's forgotten. And put something on there that's aspirational and looking to the future," says Fealty.

Over the years the gruesome history has been rebranded into a global franchise and never more successfully than in James Cameron's 1997 blockbuster starring Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet.

The film, which was the highest grossing movie until Avatar leap-frogged it in 2010, is due to be re-released for the centenary of the ship's sinking next year.

And who can blame Northern Ireland for trying to offer a different story to tourists than the Peace Walls and bloody history of the Troubles, says Fealty. "If we're famous for where that ship came from then that's no bad thing. The story we've been telling the world for the last 40 years is a much worse one."

- Published15 April 2013