Food labelling: What does it say on the tin?

- Published

The complicated job of reading food labels is set to get easier thanks to a groundbreaking EU deal, but what are the key things that campaigners want people to look out for?

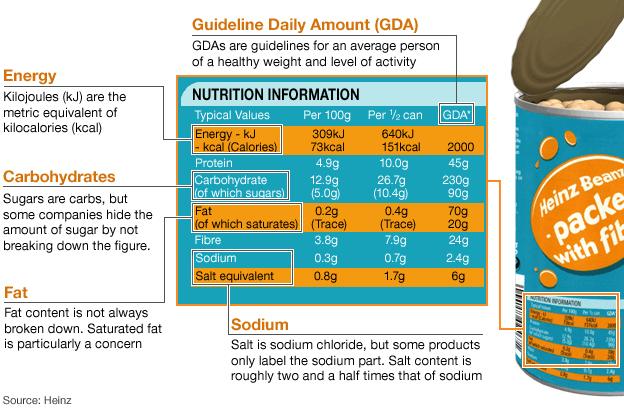

After years of argument, fierce lobbying and heated debate, the EU has agreed to bring in uniform food labelling across the 27 member countries. The rules mean labels on supermarket shelves will have to spell out energy content along with fat, saturated fat, carbohydrate, sugar, protein and salt levels.

But it could take up to five years for the harmonised labels to hit the shelves, which in many cases leaves the consumer with the often puzzling "big four" - energy, protein, carbohydrate and fat. What they actually tell us is open to debate. Take a single figure for carbohydrates, what does it tell a person about sugar content? Not very much - and that is how some companies like it, say some.

"Certain sections of the food industry want to muddy the waters," says Alan Maryon-Davis, professor of public health at Kings College London. "It benefits them if they're not too clear and so they label food in a way that can be misleading."

Many food manufacturers already list all the nutritional content the EU is now demanding. The problem in the UK is different systems are used, including the traffic light system and Guideline Daily Amounts (GDA).

"The very thing that is supposed to help you make a choice simply confuses you," says Katharine Jenner, a nutritionist with World Action On Salt and Health (Wash).

So why is it so difficult to work out what is in the food we buy?

Energy

It usually tops any food label - and can also be the start of consumer confusion.

When we eat food we convert it into energy which is used to perform bodily functions such as breathing, circulating blood, moving muscles and maintaining body temperature. This can be written in kilojoules, kilocalories and Calories - or all of them.

Food is converted into energy

Kilocalories (kcal) equivalent to 4.184 kilojoules (kJ). A kilocalorie can also be written as a Calorie - the capital "C" distinguishes it from the calories used in science.

The reason both measurements are put on labels is because they are used in different countries, says the British Nutrition Foundation (BNF). Also children often use kj while adults use kcal. Any confusion is the fault of the different measurements countries use, rather than the food industry.

Carbohydrates

Sugars are carbohydrates, but not everyone knows it. This lack of understanding means companies can disguise the amount of sugar there is in a product by not breaking down the figure to show sugar content. A single carbohydrate figure also includes starchy carbohydrates.

Sugars are carbohydrates

"People think of carbohydrates as stodge and often don't link them to sugars," says Prof Maryon-Davis.

"Certain sectors of the food industry are rather sneaky about this and don't break down the figure to show sugar content, but it's a figure that really should be there.

"It's important that we know how much sugar we are consuming and too often it's not clear to the average consumer."

Fat

Fat is fat surely? Not exactly. Some types of fat particularly need to be consumed in moderation.

Too much saturated fat is bad for you

Too much saturated fat is linked to heart disease while reasonable amounts of monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats can help lower cholesterol.

But too often the fat content is not broken down in this way. It makes choosing a healthier option much more difficult.

"Shoppers have small decision times when they are in a store," says Dr David Barling, from the Centre for Food Policy at City University London. "They are choice editing and need quick, easy information to do that."

Sodium

We are always being told to reduce our salt intake and not exceed 6g a day, but it's not so easy to work out how much you're eating. For a start salt content is not the same as sodium content and that's all some labels list.

You need to do the maths but not everyone knows that - or what the calculation is. If the label gives the sodium content, multiply by 2.5 to get the amount of salt. So 6g of salt is equivalent to about 2.4g of sodium.

Adults shouldn't exceed 6g of salt a day

In the past companies have used sodium as a way to hide just how much salt is in a product, says Jenner.

"Some companies have hidden behind the sodium label for years," she says. "But public health messages in the UK all talk about salt, so it can get confusing.

"Showing the salt content is vital. Until food manufacturers start taking more salt out of food it's down to us to control our intake. At the moment there is so much salt in food and the only way to cut down is by comparing labels."

Guideline Daily Amount (GDA)

GDAs are guidelines for an average person of a healthy weight and level of activity, but the problem is it's hard to know what average is and where you stand in comparison. If you have a sedentary job or don't exercise regularly it's likely you should eat less than the 2,500 Calories recommended for a man, 2,000 for a woman and 1,800 for a child.

"The GDAs are based on an average adult and very few of us are an average adult," says Prof Maryon-Davis. "Some of us are fat, some thin, some exercise, some don't, some have high blood pressure and others are diabetic."

Sometimes food companies also put the GDA for an adult on a product that is clearly aimed at children, he says. "It's very misleading and they know it."

But while it's not a perfect system, it does give people a quick reference point. "It would be impossible to break things down to an individual level," says the BNF. It allows people to do a quick comparison, which is what's needed in the supermarket."