A Point of View: Kim Philby and the evanescence of power

- Published

- comments

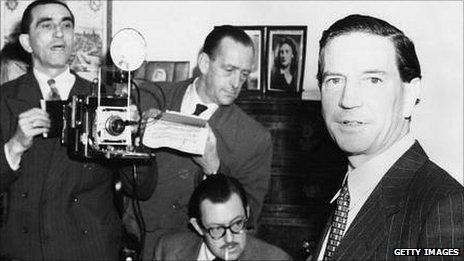

Cambridge spy Kim Philby betrayed his country because he loved power and thought history was on his side. It's a trap many others have since fallen into, writes John Gray.

You can usually learn something about people from the books they read, and occasionally you discover things they don't know about themselves.

Recently discovered letters from Kim Philby to a Cambridge bookshop show him ordering volumes by Agatha Christie, PG Wodehouse and Somerset Maugham to be sent to him in Moscow.

He also ordered books by his friend Graham Greene and another former colleague in the secret intelligence service John Le Carre, and he seems to have enjoyed the dark psychological thrillers of Patricia Highsmith. But for the most part Philby's reading was everything one would expect of a conventional Englishman of his time.

Philby's life is commonly recounted as a story of treachery, and so it was. Faced with the rise of Nazism, he believed he was justified in serving the Soviet state, which became Britain's ally for the four years between 1941 and 1945 after Hitler invaded the Soviet Union.

Philby did not live to see the collapse of the Berlin Wall and the Soviet Union two years later

In fact Philby carried on serving the Soviet cause in the Cold War when the Soviet Union had become an enemy of Britain, systematically deceiving those around him and sending some who trusted him to their deaths.

But if Philby betrayed, he was also betrayed, not by others, but by his own love of power and the conviction that he had joined an elite that had history on its side.

The idea that he had been recruited by a highly-selective and superior organisation was important to Philby. Defending his decision to become a Soviet agent in the Foreword to My Secret War, the memoir of his career as a spy that was published in 1968, he wrote, "One does not look twice at an offer of enrolment in an elite force."

This attitude becomes easier to understand if you know something of Philby's background. His father, Harry St John Philby, also known as Jack Philby and Sheikh Abdullah, was a British explorer, ornithologist and colonial intelligence officer who converted to Islam and became chief adviser to the Saudi King Ibn Saud.

Philby Sr was the pivotal figure in a deal that enabled Standard Oil, an American company, to gain the concession to the richest oilfield in the world against competition from British firms. He did this while acting as a consultant to both parties.

His motive was partly self-interest - he received a handsome retainer from Standard Oil - but there was another reason. The American bid, he claimed, was "entirely free of any imperialistic implications". At the same time he recognised the Americans were the rising power in the region.

Winning side

It's hard not to see parallels between father and son. Both underwent a conversion experience. In Kim's case to a secular creed that was supposedly based in science, but a faith nonetheless. Both double-crossed the British authorities for whom they were working.

Perhaps most importantly, both switched their allegiance to what they viewed as the winning side.

Not only in their family relations but also in their outlooks and ambitions, Kim and his father are kindred spirits in the story of Britain's imperial decline. Each was looking for a successor to the British Empire in which he could serve in a superior capacity.

The Soviet state to which Philby dedicated his life ceased to exist from 1991

Of the two men Philby Sr was probably the more successful. The Middle East in which he plotted and manoeuvred has passed away, while the authoritarian regimes that replaced Britain's imperial protectorates are now themselves challenged by the new movements of the Arab Spring.

What the upshot will be no one can foretell. But while Britain's power lasted, Harry St John Philby enjoyed all the perquisites of empire, wealth, servants and a palatial residence in the Saudi capital. In later years he seems to have suffered from boredom, but in his own terms he was a success.

His son's fate was more ambiguous. He decided to work for the Soviet intelligence service in the belief it would make him a KGB officer, but when he arrived in Moscow after his defection he discovered he was regarded as merely an agent, not wholly trusted and not even allowed into KGB headquarters.

The decline into alcoholism that followed testifies to his dismay at learning he had not been and would never be an officer in the elite force he so much wanted to join.

In one way Kim was lucky. By dying when he did he avoided witnessing the destruction of all his hopes.

In My Secret War, he observed: "I have no doubt about the verdict of history... Advances which thirty years ago, I expected to see in my lifetime, may have to wait a generation or two. But, as I look over Moscow from my study window, I can see the solid foundations of the future I glimpsed at Cambridge."

Philby died in 1988, still convinced the Soviet Union embodied the future of humankind. Only a year later the Berlin Wall came down. Just two years after that, on Christmas Day 1991, the red flag was lowered from the Kremlin. The Soviet state to which Philby dedicated his life had ceased to exist.

The solid foundations of Soviet power he saw from the window of his study were not solid at all. In a change with few historical precedents, a state that had rested on terror melted away with hardly any violence. Even the elite that Philby so much wanted to join was not interested in preserving the system.

In some ways Russia has returned to the way it was before Lenin seized power.

Elements of the former KGB are in prominent positions in government, but they preside over a peculiarly Russian type of capitalism. Whereas communism aimed to turn Russia into a modern Western society, Russia today seems happy to be different.

History's stooge

Faith in communism, the faith for which Philby betrayed his country, has vanished without leaving a trace. Some remnants of the old regime may look back with nostalgia on the Soviet era, but even they know that the radiant future for which so many millions of lives were sacrificed was never more than a mirage.

The most penetrating assessment of Philby comes not from a Kremlinologist, nor from a genuine historian, but a poet.

"Nobody knows the future - least of all those who believe in historical determinism." That was the conclusion of the Russian émigré Joseph Brodsky, writing in the early 90s.

A commemorative Russian postage stamp had appeared in which Philby was portrayed, Brodsky said, "like Alec Guinness, with a touch perhaps of Trevor Howard".

Brodsky was appalled by the idea of commemorating a figure that had played such a wretched part in one of the 20th Century's great struggles. But the conceit of historical determinism, the belief that history develops according to knowable laws, has afflicted many apart from Philby.

Who now remembers the exultant sense of triumph felt in the West when the Soviet Union disintegrated? As a response to the fall of a hideous tyranny, it was fully justified. But the feeling went much further than that. There were many who believed that an entirely new era had arrived, a glorious age of global capitalism and universal democracy.

They failed to perceive, or refused to see, the large and difficult problems that followed the Soviet collapse. Their confidence that they knew which way the world was going left them unprepared for history's reversals. These enthusiasts for democracy and the free market were falling into the trap that ensnared Philby.

The ice-cold deceiver gazing calmly out from his Moscow flat was as conventional in his political beliefs as he was in his taste in books. Along with so many of his generation, he looked forward to a new society and believed he had found it in the Soviet Union.

Unlike most of those who succumbed to this delusion, he was also a lover of power for its own sake. But the power to which he attached himself proved to be evanescent, and he ended as one of history's stooges.

The treacherous certainty that in the end betrayed Philby also betrayed many of those who celebrated the victory of the West after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Supremely confident that a Western version of capitalism was about to conquer the world, they have had to watch baffled as the West struggles to prevent its economies from collapsing. Like Kim Philby, they failed to understand that the only genuine historical law is a law of irony.

- Published30 June 2011