From Zimbabwe to South Africa in search of an education

- Published

The collapse of affordable schooling in Zimbabwe is leading thousands of children to make a perilous trek to South Africa. But some of those who make it, penniless, to Johannesburg, get what they want - a top-quality education.

The wide Limpopo river that separates Zimbabwe and South Africa is known for its crocodiles, snakes and unpredictable currents. But for Zimbabwean children crossing the border, alone, it is human beings who pose the biggest danger.

Moses Matenere was 17 years old when he made the crossing a couple of years ago.

Trapped in the lawless no-man's-land between the Limpopo river and the electric fence that stretches along South Africa's border, the teenager was attacked by a gang of armed thieves - known locally as the Magomagoma.

The gang robbed Moses, threatening him by holding a knife under his legs. They then forced him to watch other men captured by the gang, as they were told to rape young girls.

"They just rape... it happened in front of my eyes," he remembers, shuddering with the pain of the memory.

Sacrifices

Back in Zimbabwe, Moses came from a family with connections. As a member of the ruling Zanu-PF party, Moses' father got his son into a good school.

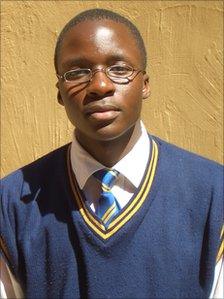

Moses Matenere dreams of returning home as a qualified doctor

At the time, Zimbabwe boasted one of the best education systems in Africa, but in 2008, amid hyperinflation and political violence, the country sank into chaos.

Teachers went unpaid, and school fees rocketed. When Moses' father died, his mother could no longer pay the bills and had to withdraw her son from school.

Most Zimbabwean families still value education, however, and believe it is worth making sacrifices for.

So a couple of years ago, Moses' mother packed him some rice scones and he joined the invisible train of children living on the streets, begging and heading to South Africa.

It was not an easy journey.

After his encounter with the Magomagoma at the border, Moses managed to get to Johannesburg in a shared taxi, persuading the driver that his cousin in the city would pay the fare on their arrival.

But the cousin never turned up and the driver took his revenge, holding Moses hostage for more than a week, and beating him with ropes.

When he finally escaped, he found his way to the Central Methodist Church.

This is a sanctuary for Zimbabweans in Johannesburg, who make up a large proportion of the 1,000 or more destitute people who sleep on its floor every night.

Any unaccompanied children who turn up are helped out on the fourth floor by volunteer Takudzwa Chikoro, a former child migrant himself, now aged 21.

"Most of the children have stories," he tells me, in the dark, as children sleep on the floor around him.

"Some have been raped, some have been robbed."

Cambridge syllabus

Takudzwa has his own harrowing story. At the age of 16, he too was robbed by the Magomagoma - rumoured to be former Zimbabwean soldiers - and then had to walk across the South African bush drinking from waterholes used by wild animals.

After he arrived in Johannesburg, he slept rough and worked for traditional African healers - sangomas - some of whom put children to work in the criminal underworld.

But like Moses, one day he arrived at the Methodist church. He was given a bed in a church dormitory in Soweto, and a place at the church-run Albert School.

The church is sometimes criticised for the squalor of the living conditions it provides for adults and children. But for the Zimbabwean migrant children who make up the majority of the Albert School's pupils it provides what they want most - an education similar to the one they began in Zimbabwe.

"They tend to feel that what [other] South African schools have on offer is not what they want," says Anne Skelton, Director of the Centre for Child Law at the University of Pretoria.

"The older and more advanced they are with their studies, the more particular they are about the education they are accessing."

Pupils at the Albert school study the Cambridge International syllabus, which awards O-levels and A-levels similar to those traditionally studied in British schools - and in both exams, more than 70% of pupils pass with grades between A* and C.

Dried-out drain

Takudzwa has already passed his A-levels and is hunting for a university scholarship to study law abroad, in the hope of becoming a human rights lawyer.

The border town of Musina is "not a nice place" for young Zimbabwean migrants

He was offered a place at Dundee University in the UK, but could not take it up because, as a former illegal migrant, he didn't have a valid travel document - a common problem for pupils at the Albert School.

Moses is now in form three, with ambitions of becoming a doctor, and returning triumphantly to his mother in Zimbabwe.

"She will be proud," he beams. "I have a bright future ahead of me now."

Success stories like these motivate other Zimbabwean children to undertake the dangerous trip south.

In the South African border town of Musina, new arrivals sleep rough on the streets, congregating on a notorious patch of waste ground. Some mix with older teenagers, who drink and sniff glue.

"It's not a nice place," says 12-year-old Takwant, an orphan who crossed the border illegally last year. "No money for soap, no toilet, no house, no bath."

He sleeps in a dried-out drain with his friends, 10-year-old Talent, and Justin, 15.

"I want to go to school," says Justin. "If I go to school I can change my life, I can live with cars and wives and daughters."

His ambition is to save up to join an uncle in Johannesburg. For now, he survives by begging.

You can listen to Crossing Continents, external on BBC Radio 4, external on Thursday 8 September at 11:00 BST and Monday 12 September at 20:30 BST. You can also listen via the BBC iPlayer, external or the podcast, external.